Having looked at these features of the Auerstadt

battlefield, it was time to press on to Jena, though we did have time

to call into the village of Auerstadt itself to see the building that

had been Prussian headquarters (this village is very small, some

way from the battlefield and well off the main road: does anyone

know how it gave its name to the battle?).

Having looked at these features of the Auerstadt

battlefield, it was time to press on to Jena, though we did have time

to call into the village of Auerstadt itself to see the building that

had been Prussian headquarters (this village is very small, some

way from the battlefield and well off the main road: does anyone

know how it gave its name to the battle?).

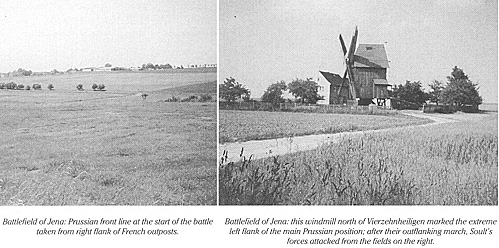

Battlefield of Jena: Prussian front line at the start of the battle taken from right flank of French outposts.

Battlefield of Jena: this windmill north of Vierzehnheiligen marked the extreme left flank of the main Prussian position; after their outflanking march, Soult's forces attacked from the fields on the right.

Arriving at the village of Cospeda in time for a packed lunch, we first visited its little museum, the chief features of which are another diorama and a large relief model of the battlefield. From there we walked over to the site of Napoleon's headquarters on the Landgrafenburg, and from there followed the route of the French advance towards the site of the line held by Tauentzien's division at the start of the battle (securely protected by deep ravines on either flank and resting on a large hill that blocks off the end of the Landgrafenburg promontory, it is easy to see how he was able to hold out for the two hours that he did).

Picked up by the bus, we then drove the mile or so to the site of the main action, alighting first at a spot on the road from Cospeda to Vierzehnheiligen from which it is possible to view the whole of the French position, the spot where Ney's men were attacked, and the bulk of the position adopted by Hohenlohe.

Battlefield of Jena western face of the village of Vierzehnheiligen showing the gardens and orchards held by the French during the attack of Von Grawert.

The author photographed near the spot where Victor de Saint Simon was wounded on the battlefield of Jena,

From there we drove the short distance to Vierzelmheiligen, and, in particular, walked around the north-western outskirts of the village, contrasting the open fields over which Von Grawert launched his attack with the gardens and orchards in which the French defenders sheltered.

After that, it was on to a windmill perhaps half-a-mile to the north of Vierzehnheiligen. Shown on contemporary prints of the battle, this marked the extreme left wing of Hohenlohe's forces and, in addition, the western end of a long valley which eventually debouches into the valley of the Saale some miles to the east. Entered by Soult near the village of Rodigen, this formed an ideal line of approach for his troops, and it is easy to see how the sudden eruption of his corps from its western tip must have demoralised the Prussians.

Last but not least, it was on to the Ruchel Tower, a large brick edifice just outside the village of Frankendorf a mile or two to the west that commemorates the site of the last Prussian attack, its summit affording an excellent view both of the fields in which Ruchel's men fell, and the route of the Prussian retreat towards Weimar.

By now, as readers will appreciate, I was more than ready for a shower and a good meal, but no such luck: although the party was going on to a hotel, I had to get back to Berlin to catch an early- morning flight home, so I was dropped off at the station and caught an evening train for the capital, this at least giving me time to collect my thoughts. These, needless to say, were many, but not the least important concerned a distant ancestor of mine -- a cousin of my great-great-great grandmother -- named Victor de Saint Simon.

An officer in Napoleon's army, after the wars he wrote his memoirs, the manuscript of which still survives. In 1806 an aide-de- camp with Marshal Ney, he left a vivid account of Jena which begins with him being sent by Ney, who was then some miles east of Jena, to Napoleon the night before the battle with a message to the effect that the marshal was coming up at the head of a small advance guard and would throw himself upon the Prussians as soon as he arrived. After fighting his way up the narrow track that was the only direct route from Jena to the Landgrafenburg, Saint Simon reached Napoleon's headquarters just as the battle began to be greeted by Marshal Berthier with the pleasing news that he had been awarded the Legion of Honour.

Napoleon, however, was far less welcoming, and packed him straight off to Ney with the message that he was at all costs not to provoke a general action as the emperor wanted to wait for all his forces to come up before launching his attack. Back down the track galloped Saint Simon, only to find that Ney had passed through Jena before he got there, the reason that he had missed him being that the marshal had taken the alternative route up to the plateau that branched off to Cospeda a couple of miles along the main road to Weimar.

Setting off in hot pursuit, Saint Simon reached the heights again only to find himself plunged into fog so dense that he could not see ten paces. Unable to find Ney or anyone else, he wandered about until he was suddenly chanced upon by a Prussian cavalry patrol. There followed a brief but violent struggle in which Saint Simon received a number of serious sabre wounds, but his horse broke free and bolted through the fog.

Literally a moment later, horse and rider crashed straight into the arms of a substantial force of French troops who turned out to be none other than the troops they had been looking for. Falling to the ground, Saint Simon just had time to gasp out that he had a message for Ney, when suddenly all hell broke loose as large numbers of Prussian troops burst through the fog on all sides.

Immediately the French formed square, only to see the Prussians deploy a battery of artillery at point-blank range. Not for nothing was Ney called the 'bravest of the brave', however.

Calling out to his men that they should dive for the ground the moment he gave the order, he waited until he saw the gunners' linstocks flare in the touchholes and then yelled 'Duck!' Unbelievably, this actually worked, the Prussian canister simply going straight over his men's heads. However, the danger was by no means over as the Prussians had followed the canister with a massive cavalry charge which was now rolling towards the huddled troops. Leaping to their feet, the French proceeded to beat them off with aplomb, Saint Simon describing how he saw the first two ranks of the square passing their muskets back to be reloaded by the men behind them.

In the midst of all this, however, he now passed out from pain and loss of blood. As I think readers will agree, it is a quite extraordinary story.

Jena and Auerstadt

Back to Napoleonic Notes and Queries # 16 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1995 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com