In June this year I was lucky enough to be asked to Germany

to conduct a battlefield tour for a group of officers from the

American 502nd Infantry based in Berlin.

In June this year I was lucky enough to be asked to Germany

to conduct a battlefield tour for a group of officers from the

American 502nd Infantry based in Berlin.

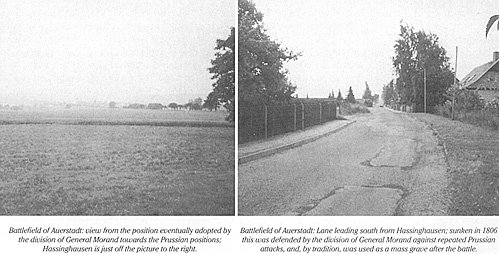

Left: Battlefield of Auerstadt: view from the position eventually adopted by the division of General Morand towards the Prussian positions; Hassinghausen is just off the picture to the right.

Right: Battlefield of Auerstodt: Lone leading south from Hassinghausen; sunken in 1806 this was defended by the division of General Morand against repeated Prussian attacks, and, by tradition, was used as a mass grave after the battle.

They had been studying the campaigns of Jena and Auerstadt, and it was my brief, first, to deliver a lecture on the campaign at American headquarters, and, second, to lead a 'staff ride' round the battlefields themselves. This was somewhat daunting - not only was notice rather short, but I am no expert on Napoleon's campaigns in Germany - but there is nothing like a challenge, and so the morning of 20 June saw me winging my way to Berlin.

On my arrival, American hospitality proved as warm as ever -- I was met at the airport by a pair of very courteous young lieutenants and put up in a most swish army guesthouse, which in an earlier incarnation had apparently been a favourite watering-hole of the Nazi top brass. However, after an excellent lunch, it was down to business, and I spent the afternoon taking my hosts through the campaign.

Beginning with an outline of the background to the war that broke out between France and Prussia in 1806, I went on to compare and contrast the opposing armies, to discuss their moves, and finally to look at the battles themselves, all of which took a considerable time. Then, after an evening spent planning the visit to the battlefields, at 4 a.m. I was up to catch the coach that was to take us all down to Saxony. From Berlin it was a considerable distance, and it was not until 9.30 a.m. that we pulled into Hassinghausen, which is the village that was the focal point of the battle of Auerstadt.

At this point a brief summary of the campaign itself might be of value. Invading Saxony at the end of September 1806, Napoleon had, albeit without realising it, managed to get round the left flank of the Prussian army so that he was threatening its communications with Berlin. As soon as he realised what was happening, the emperor hastily switched the Grande Armee's line of march to the west in the intention of taking the Prussians in the flank and rear. However, matters did not quite work out as he planned, for the Prussians were now themselves marching north- eastwards in a desperate bid to reach safety.

As a result the two sides collided with one another on 13- 14 October in a most messy and confused fashion on the heights that overlook the western flank of the river Saale. Whilst Napoleon himself surprised a Prussian flank-guard that had been detached to watch the crossings of the Saale around Jena under Prince Hohenlohe with the bulk of the grande armee, the isolated corps of Marshal Davout, which was far out on the French right, suddenly found itself confronted with the main Prussian column under the Duke of Brunswick. Faced by odds of well over two to one, Davout kept his head, and pulled off one of the most extraordinary feats of the Napoleonic Wars.

Feeding his three tired divisions -- they had been marching all night -- into line as they arrived, the marshal first secured the village of Hassinghausen which blocked the road along which the Prussians were retreating, and then gradually extended his flanks to right and left. As he did so, the Prussians launched a series of ferocious assaults on his positions, but each of these in turn was beaten off, Davout eventually throwing forward both his flanks and pressing the increasingly demoralised enemy, whose commander had by now been moratally wounded, back into a huddle in the valley bottom directly below Hassinghausen, whereupon they eventually disintegrated altogether.

At Jena, meanwhile, Napoleon had been having a much easier time of it, his worst enemy probably being the dense fog that blanketed the battlefield for most of the day. Increasingly outnumbering the Prussians as the day went on, he first broke out of the narrow lodgement that his troops had secured the previous night on the isolated promontory of the Landgrafenburg by defeating the division of General von Tauntzien, and then wheeled his army to the left in a great turning movement.

For some time Hohenlohe's main forces held the French on a line running roughly northwards from the village of Isserst%odt - the advanced guard of Ney's corps was very roughly handled when it penetrated the midst of the Prussian positions, whilst the division of General von Grawert launched a sustained assault upon the village of Vierzehnheiligen, which for some time marked the French right flank - but some time after noon Hohenlohe was hit in the left flank by the corps of Marshal Soult which had swung in a great arc around Napoleon's right flank.

Simultaneously charged from the front by Murat's cavalry, the Prussians fled in rout to the west. However, the fight was not yet over, for, just as they did so another force of Prussian troops appeared on the battlefield from the same direction under General R.chel. With more valour than discretion, this worthy launched his forces in an uphill attack on the oncoming French, only for his men to be overwhelmed in their turn and themselves forced to flee, the result being that by 2 p.m. on 14 October the entire Prussian army had been beaten.

So much for the actual fighting. It remained to be seen, however, what there was actually to visit. In the event the answer was 'a great deal'. Neither battlefield has changed in the slightest since 1806 - indeed, many of the roads across them remain mere cart-tracks. Beginning with Auerst%odt, the village of Hassinghausen is an obvious jumping-off point for a most interesting tour.

In the village itself, the old rectory - the Pfl/oorrhaus which in 1806 was used as a dressing station, contains a small museum which holds an excellent diorama of the action as well as a number of objects of interest, including a bloodstained parish register which was used by French surgeons to prop up the limbs that they were amputating. Also of note is a large walled farmyard at what in 1806 would have been the western end of the village, this being an obvious strongpoint. Leading off the main road to north and south just by this farm are two lanes which mark the French frontline.

The one to the north was held by the French from the start of the battle, but that to the south was only occupied later. Both are lined with bushes and small trees, whilst in 1806 the latter was sunken (now level with the level of the surrounding ground, it was according to local legend used as a ready-made mass grave). Beside the lane to the north a couple of hundred yards from the edge of the village, there is a small mound. Partly dug out, and evidently much smaller than it would have been in 1806, this marks the site where Davout deployed his corps artillery, and commands a superb view of the field. As to the ground, meanwhile, this consists of open rolling wheatfields that would constitute no problem for either cavalry or infantry. Indeed, viewed from the French position, even the gradients appear very gentle - only when one descends into the valley in front of the French line does one realise that in places the slopes are actually very steep, this being particularly apparent from the monument that marks the spot where Brunswick was mortally wounded leading a Prussian attack to the southwest of Hassinghausen.

Having looked at these features of the Auerst%odt battlefield, it was time to press on to Jena, though we did have time to call into the village of Auerst%odt itself to see the building that had been Prussian headquarters (this village is very small, some way from the battlefield and well off the main road: does anyone know how it gave its name to the battle?).

Arriving at the village of Cospeda in time for a packed lunch, we first visited its little museum, the chief features of which are another diorama and a large relief model of the battlefield. From there we walked over to the site of Napoleon's headquarters on the Landgrafenburg, and from there followed the route of the French advance towards the site of the line held by Tauentzien's division at the start of the battle (securely protected by deep ravines on either flank and resting on a large hill that blocks off the end of the Landgrafenburg promontory, it is easy to see how he was able to hold out for the two hours that he did).

Picked up by the bus, we then drove the mile or so to the site of the main action, alighting first at a spot on the road from Cospeda to Vierzehnheiligen from which it is possible to view the whole of the French position, the spot where Ney's men were attacked, and the bulk of the position adopted by Hohenlohe. From there

Battlefield of Jena western face of the village of Vierzehnheiligen showing the gardens and orchards held by the French during the attack of Von Grawert.

The author photographed near the spot where Victor de Saint Simon was wounded on the battlefield of Jena, we drove the short distance to Vierzelmheiligen, and, in particular, walked around the north-western outskirts of the village, contrasting the open fields over which Von Grawert launched his attack with the gardens and orchards in which the French defenders sheltered.

After that, it was on to a windmill perhaps half-a-mile to the north of Vierzehnheiligen. Shown on contemporary prints of the battle, this marked the extreme left wing of Hohenlohe's forces and, in addition, the western end of a long valley which eventually debouches into the valley of the Saale some miles to the east. Entered by Soult near the village of Rodigen, this formed an ideal line of approach for his troops, and it is easy to see how the sudden eruption of his corps from its western tip must have demoralised the Prussians.

Last but not least, it was on to the Ruchel Tower, a large brick edifice just outside the village of Frankendorf a mile or two to the west that commemorates the site of the last Prussian attack, its summit affording an excellent view both of the fields in which Ruchel's men fell, and the route of the Prussian retreat towards Weimar.

By now, as readers will appreciate, I was more than ready for a shower and a good meal, but no such luck: although the party was going on to a hotel, I had to get back to Berlin to catch an early- morning flight home, so I was dropped off at the station and caught an evening train for the capital, this at least giving me time to collect my thoughts. These, needless to say, were many, but not the least important concerned a distant ancestor of mine -- a cousin of my great-great-great grandmother -- named Victor de Saint Simon.

An officer in Napoleon's army, after the wars he wrote his memoirs, the manuscript of which still survives. In 1806 an aide-de- camp with Marshal Ney, he left a vivid account of Jena which begins with him being sent by Ney, who was then some miles east of Jena, to Napoleon the night before the battle with a message to the effect that the marshal was coming up at the head of a small advance guard and would throw himself upon the Prussians as soon as he arrived. After fighting his way up the narrow track that was the only direct route from Jena to the Landgrafenburg, Saint Simon reached Napoleon's headquarters just as the battle began to be greeted by Marshal Berthier with the pleasing news that he had been awarded the Legion of Honour.

Napoleon, however, was far less welcoming, and packed him straight off to Ney with the message that he was at all costs not to provoke a general action as the emperor wanted to wait for all his forces to come up before launching his attack. Back down the track galloped Saint Simon, only to find that Ney had passed through Jena before he got there, the reason that he had missed him being that the marshal had taken the alternative route up to the plateau that branched off to Cospeda a couple of miles along the main road to Weimar.

Setting off in hot pursuit, Saint Simon reached the heights again only to find himself plunged into fog so dense that he could not see ten paces. Unable to find Ney or anyone else, he wandered about until he was suddenly chanced upon by a Prussian cavalry patrol. There followed a brief but violent struggle in which Saint Simon received a number of serious sabre wounds, but his horse broke free and bolted through the fog.

Literally a moment later, horse and rider crashed straight into the arms of a substantial force of French troops who turned out to be none other than the troops they had been looking for. Falling to the ground, Saint Simon just had time to gasp out that he had a message for Ney, when suddenly all hell broke loose as large numbers of Prussian troops burst through the fog on all sides.

Immediately the French formed square, only to see the Prussians deploy a battery of artillery at point-blank range. Not for nothing was Ney called the 'bravest of the brave', however.

Calling out to his men that they should dive for the ground the moment he gave the order, he waited until he saw the gunners' linstocks flare in the touchholes and then yelled 'Duck!' Unbelievably, this actually worked, the Prussian canister simply going straight over his men's heads. However, the danger was by no means over as the Prussians had followed the canister with a massive cavalry charge which was now rolling towards the huddled troops. Leaping to their feet, the French proceeded to beat them off with aplomb, Saint Simon describing how he saw the first two ranks of the square passing their muskets back to be reloaded by the men behind them.

In the midst of all this, however, he now passed out from pain and loss of blood. As I think readers will agree, it is a quite extraordinary story.

Jena and Auerstadt

Back to Napoleonic Notes and Queries # 16 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1995 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com