FORAGE CAP

FORAGE CAP

The type of forage cap worn by the 68th in 1814 is open to conjecture. But in all probability the regiment was supplied with the new universal forage cap upon its return from the Peninsular war. A universal forage cap had first been proposed in 1811. By 6812 forage caps for the infantry were ordered to be made in strict conformity to an approved pattern though the official pattern was not approved until 1813.

Detail from 'View Of A Part Of The Camp Of The English Troops In Bois De Boulogne At Paris.. .'1815. (Photo, author's collection). Items worthy of attention are the knitted woollen forage caps, the white wool forage jackets (waistcoats), the musket rack and the use of bell tents.

The universal forage cap was of a flared or pork pie shape and made of knitted wool, milled, making it waterproof and giving it the appearence of cloth. The main body of the cap was of a red colour whilst the lower band was of the regimental facing colour, though there could be regimental peculiarities. Regimental numbers were worn at the front in roman or arabic numerals, and usually made of worsted wool. Previous to the adoption of this cap there appears to have been two common styles of forage cap worn, the "night cap" shape and the "folding" shape. These varieties are displayed in numerous period illustrations, including works by Pyne and Atkinson. Despite being superseded by the universal cap, these styles did not go out of use immediately. It took time for the new cap to work through the system. Indeed a print of infantry c1826, playing football, shows the "folding" pattern cap still in use.

When not in use the cap was either stored in the soldiers shako or carried in his knapsack. Earlier illustrations show the cap being carried above the ammunition pouch in a tin or leather case or simply fastened with straps; though these methods seem to have died out as the war progressed.

FORAGE JACKET

Also called a sleeved waistcoat, this article of clothing was one of the last vestiges of the 18th century uniform. It had originally developed from the waistcoat worn under the old pre-1796 redcoat but by 1814 had developed into a tight fitting garment worn on fatigues or under the regimental jacket. Some evidence suggests it having tails but these appear to have been gradually discontinued towards the end of the period. Indeed Horse Guards complained that the waistcoat was,". . . reduced so much in its dimensions, as to afford little warmth in winter, and to be totally useless for the essential purpose for which it was intended, viz as a fatigue dress in barracks during the summer".

In appearence the forage jacket consisted of a collar, cuffs and shoulder straps of regimental facing colour. The rest of the jacket was made of kersey with serge sleeves, the whole of which was sometimes pipe-clayed. Indeed, one of the reasons for the demise of the white forage jacket in 1830 was the detrimental effect pipe-claying the jackets had on the men's health.

SHIRTS

Officially two shirts only were to be purchased by each man in the 68th by 1814. Previously it had been three, but to cut down the weight in the knapsack the number was reduced to two in 1812. The weight of each shirt being 1 lb. Some regimental necessary lists though still provided for three shirts.

There seems to be a movement in some regiments at the time to replace linen shirts with flannel ones, the flannel shirts being considered healthier for the men rather than the linen ones. Battalion orders 2/89th dated July 1814 read, "It having been represented that some of the men have been supplied with flannel shirts are in the habit of occasionally wearing linen ones, and such a thing being prejudicial to their health ... Officers commanding companies will be pleased to sanction and enforce the disposal of their linen ones when flannel ones are furnished".

Whether all regiments adhered to this trend is unknown. Certainly the 68th received a supply of flannel shirts. Green mentions, "arrived in good health at Pedrogas, with about 800 new flannel shirts for the regiment, the shirts were full sized with long sleeves, which I have no doubt had a tendency to preserve health, more than linen shirts could do."

This though does not mean all the 68ths shirts were made of flannel, shirts of linen could still have been worn by the men.

CROSSBELTS AND PLATES

The crossbelts worn by the 68th in 1814 were those of the size introduced by Sir John Moore in 1808. In that year Moore supplied the 52nd Light Infantry with belts 1/2 inch broader than the 2 1/8 inch belts ordered by the 1802 regulations. The width of the new belts, "Being found quite equal to the weight of the ammunition and comfortable to the soldier in every respect".

As the orders converting the 68th to light infantry stated, "assimilated with regard to their clothing, arming and discipline to the 43rd and 52nd Regiments". It is probable that these new belts were issued to the 68th too; and are possibly the ones Green mentions,"At christmas (1808) our new clothing was ready ... and a complete set of new accoutrements".

The appearance of the 68th crossbelt plate is conjectural, there being no known existing belt plate from this period. As the 68th were to be equipped along the same lines as the 43rd and 52nd Light Infantry, there might be a case for the 68th being issued with the same type of plate too. A print from Goddard and Booths, "Military Costume of Europe" 1812, shows a soldier of the 43rd wearing "43" on a plain plate. Also a Hamilton Smith print of 1812 of a 52nd soldier clearly shows a "52" on a plain plate. All the 1802 regulations specify is, "The plate of the bayonet belt to have the number of the regiment". It is presumed in the absence of evidence to the contrary the 68th followed the example of the 43rd and 52nd, and the 1802 regulations, in having a plain 68 on the belt plates, though there is the possibility, given the archaeological finds in Canada, that the plate may have displayed a stringed bugle horn with the number 68.

Finally each soldier was to be provided with a brush and picker, and this was to be attached to the bayonet belt. In reality it was probably attached to the rear of the cross belt plate.

AMMUNITION POUCHES

AMMUNITION POUCHES

Prior to the departure for Portugal the 68th inspection return of 31st May 1811 noted the unit as having three different patterns of ammunition pouch. As there are no more references to this matter in later inspection returns, it seems the 68th had replaced any older pouches before they sailed to Portugal later that year, the replacement pouches in all probability being the sixty round pouch which had first been introduced in 1808.

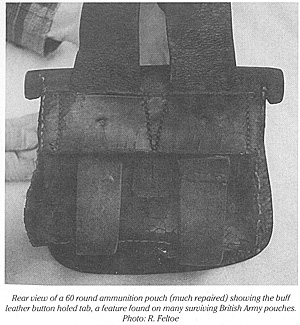

Rear view of a 60 round ammunition pouch (much repaired) showing the buff leather button holed tab, a feature found on many surviving British Army pouches. Photo. R. Feltoe

A description of the sixty round pouch, which was to become the standard pattern in the latter part of the war, states," English cartridge boxes are leather japaned and have a tin box divided into three compartments in which the cartridges are put in paper bundles of twenty each making sixty rounds, and the name and number of the soldier is put on each bundle. Just as they are going into action the bundles are undone and the cartridges thrown loose into the tin box. There is an undercover of leather to effectively keep out wet. By long experience during wars for the past forty years it is found that it is much the best mode to have tin canisters or boxes in the above described boxes instead of blocks of wood with a receptacle for each cartridge. The cartridges are more easily got at, and they are less likely to be broken in taking them out in action". It could also be added that unofficially the wood blocks would have made good kindling for a fire besides lightening the weight a soldier had to carry.

In some cases the sixty round pouch could be constructed with the leather of the pouch flap rough side out, one theory being that the blacking from the blackball when applied to the rough side of the leather adhered better, than if applied to the smooth side, thus making the pouch water-proof.

On the bottom of the pouch were two blackened iron buckles and a leather button. The buckles were to fasten the pouch belt, and the button was to secure a buff leather strap which was stitched to the inside of the flap. No stitches pierced the outside of the flap, a characteristic found on all British pouches. On the rear of the pouch was a retaining bar for guiding the pouch belt. The stitching in the centre of the bar could be sewn either in two straight lines or in a "V" depending on the position of the two iron buckles. If the buckles were sewn offset the stitching was "V' shaped probably to throw the pouch belt outwards so it fitted the soldier better. If the buckles were sewn on square the stitching was straight. Also in the middle of the bar was sewn a buff leather button holed tab, which was used to secure the pouch behind the soldier.

FIRELOCK AND BAYONET

The musket used by the 68th was of the New Land Light Infantry pattern. This had been approved by Horse Guards in 1803 and described as follows,"The barrel shall be browned ... that a grooved sight shall be fixed at the breech end of the barrel and that a canvas cover similar to that used by the Austrian troops, shall be provided for the purpose of covering and protecting the butt and lock of each piece".

Green describes them as, "Japaned muskets with double sights" and as having been issued at Christmas 1808. However no records exist to show any production prior to 1811. Green wrote his memoirs some years after the event. He might have been mistaken or there was an earlier production of which there is no record.

Besides having a backsight, the .75 calibre, 39 inch long browned barrel was retained by three flat captive keys and the upper swivel screw, a system similar to the Baker Rifle. The stock was much simpler in comparison to its predecessors and had a scroll trigger guard forming a pistol grip.

The bayonet was of the new land pattern having a socket 3 inches long attached to which was a spring. The spring engaged the foresight of the musket preventing its accidental withdrawal when fixed.

KNAPSACKS

KNAPSACKS

The knapsack used by the 68th in 1814 was most probably the envelope knapsack first introduced in 1805. Sir Charles Napier when talking about the famed Shorricliffe Camp had this to say, "...there a Knapsack was composed on so good a pattern that every deviation from it has since proved a failure". As the 68th were equipped in the fashion of the 43rd and 52nd, who were trained at Shorricliffe, then presumably it was this type of knapsack which the regiment used in 1814.

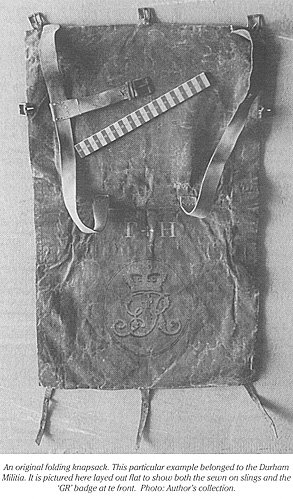

An original folding knapsack. This particular example belonged to the Durham Militia. It is pictured here layed out flat to show both the sewn on stings and the 'GR'badge at te front, Photo: Author's collection.

Unlike the earlier knapsacks which were," little better than a large letter bag into which the various necessaries were promiscuously thrown and carried by straps sewn to the material and united to a breast strap in front", the 1805 envelope knapsack," . . . now appeared furnished with gores in the sides, one of which contained a pocket for brushes, and it was carried in buff slings".

The knapsack was made from black painted canvas material enveloped shaped and formed around a wooden frame. The frame gave the knapsack its rigid shape, but on occasion might be unofficially used for firewood when cooking in the field, which might explain some of the shapeless packs carried by soldiers in contemporary prints.

It was not until 1811 that a report recommended that a universal knapsack be adopted by the army. This was accepted and confirmed in the 1812 regulations. In all probability it was the 1805 envelope knapsack that was adopted.

The knapsack was to be made in strict conformity to an approved pattern with the Regimental number marked on the back without ornament, and for the first time the knapsack was to be of the same dimensions and colour for the whole army. Finally the whole of the necessaries to be carried by soldiers, in the knapsack, shall not exceed the weight of twelve pounds and a half, the knapsack and greatcoat included".

Later in 1812 experiments took place in waterproofing the knapsacks. Messrs. Bicknell and Moore adopted the expedient of Japaning the canvas material which waterproofed and gave durability of colour to the knapsack to the advantage which, the knapsack derived from this process, the Colonels of Regiments, then serving in the Peninsula, bore ample testimony".

There was another type of knapsack commonly used by the army, this being the Folding knapsack, though its use gradually diminished as regiments re-equipped with the envelope knapsack. In contrast to the envelope knapsack, the folding knapsack consisted of a canvas body folded into two equal halves with two large internal pockets on each side and a long thin pocket across the spine. The straps of buff leather were sewn straight onto the canvas, but with a leather reinforcement on the inside.

There were two main problems experienced with both the 1805 envelope knapsack and the folding knapsack. The first was the chest strap. One veteran remembered,"[ was often subject to a violent pain in my chest, particularly after parading in heavy marching order ... I clearly saw what was the cause of my complaint and afterwards avoided as much as possible buckling the breast strap", he further records unbuckling his breast strap on the march to Talavera and that, "The other men occasionally unbuckled theirs, and some hot heads threw them away altogether". The second problem was the actual load carried. Cooper of the Seventh recorded his load as being 61 lbs. including his knapsack and Rifleman Harris recalled, "Many a man died, I am convinced, who would have borne up well to the end ... but for the infernal load we carried on our backs".

The army itself was aware of the problem and tried to find a practical solution. However it was not until 1812 that the weight limit was restricted to twelve and a half pounds per soldier, "unless it should be deemed expedient on particular occasions, to order the soldiers to carry a greater than ordinary proportion of provisions. The blankets, as well as any other extra articles which it may be found necessary to carry with the troops, are to be conveyed by the commissariat".

HAVERSACKS AND CANTEENS

These pieces of equipment were issued on campaign or troop movements. Until use, they were kept in Ordnance stores and were thus not an every day item. The Haversack consisted of an unbleached linen bag and strap, the body of the Haversack being roughly thirteen and a half inches by seventeen and a half inches wide, with a flap secured by two buttons. The Haversack contained the three days ration usually issued to the troops, and was worn on the left hip.

A pre-1814 report criticised the material used to construct the Haversacks. In wet weather the bread carried in these bags was being damaged and rendered useless. A new pattern Haversack with a painted cover to keep out the wet was recommended but does not seem to have been taken up.

The three pint canteen was also carried by a leather strap on the left hip. These circular oak canteens painted a Prussian or Ordnance blue, were made of wood segments around the edges and two larger central pieces. They were held together by two iron bands, no nails or fixtures attached the bands to the wood. The swelling of the damp wood kept the bands in place.

On one side of the canteen a B 0 was branded or cut, earlier examples having a G R. There is little indication that the B 0 was painted on a canteen. A brand cannot easily be removed and the evidence left by any removal would be a sure indication that it had once been government property, whereas a painted marking could easily be rubbed out. However canteens were often painted with the regiments and soldier's name and number.

GREATCOATS

The other ranks greatcoat which evolved by 1814 would be single breasted and made of "dark grey woolen stuff kersey wove, loose made", lined with serge. Instructions in 1812 for army store- keepers noted that 3 1/3 yards of kersey was to be used to make a greatcoat. The greatcoat, having to be worn over the jacket, waistcoat and shirt (and in some cases accoutrements) was loosely made.

Originally it had reached down to (or below) the calf of the leg, but in 1811 a report recommended that the length of soldiers greatcoats be reduced so as to reach an inch only below the knee in order that it may not impede his marching, as well as to keep it within a proper weight".

A cape came down well over the shoulders, under which were two shoulder straps which served to keep the cross-belts in place. It had been recommened that,"the cape should be fastened at the corners and behind, so as to prevent the men drawing it over their ears when on sentry, or the wind blowing it in their eyes in tempestuous weather".

There is little evidence to suggest this was carried out at the time, though by the Crimean period the capes were buttoned down at the front. The greatcoats were water-proofed as early as September 1804,"In consideration of the essential benefit in point of health and comfort that will result . . ." Further correspondence on the subject occurred in 1813, indicating that troop trials were used in selecting the best process for waterproofing the coat.

The greatcoats were renewed if necessary every three years, except for,"those serving in Canada, Nova Scotia and in regiments engaged in constant active operations in the field..." Then the greatcoats could be renewed every two years. Regulars such as the 68th were provided with the best or first quality greatcoats, "generally known by the number 1 plus S G marked on various parts of the inside of the greatcoats". Greatcoats of a second quality were known by a number 2, plus S G marked in a similar way. Presumably these went to the Militia. The greatcoats came in four sizes. One greatcoat in every 31 of size 4; the remaining 30 coats to be equal proportions of sizes no. 1,2,3. Finally, one sealed pattern coat of the three sizes 1,2,3, accompanied every issue and formed part of the supply.

The soldiers were only to wear the greatcoat in bad weather or when ordered to do so. Standing Orders for the 95th stating, "nor is he to appear in his watchcloak, unless it actually rains or snows, from the first relief after the reveille, till sunset". Presumably this was to save wear and tear, and as the coats were provided at public expense, it saved tax-payers money too.

However, in the field things could be slightly different; Wellington to Lord Liverpool, October 1811, "As the soldiers of the army frequently sleep out of doors, and as, even when in houses, they are obliged to sleep in their greatcoats, that article of equipment wears out in a much shorter period of time than that specified by the regulations ... I request your Lordship that 10,000 greatcoats ... may be sent". Both Wheeler and Cooper in their memoirs give excellent descriptions of sleeping in greatcoats.

The greatcoats were carried, either rolled on top on the Knapsack or slung by greatcoat straps on the soldiers back. The straps were generally used for light marching order or guard order. For the Vittoria campaign 1813, soldiers were ordered to leave greatcoats behind," . . . to relieve them from a part of the weight, which they would otherwise be obliged to carry . . .". This was also because Bell Tents were now provided for the troop's shelter. The greatcoats presumably followed in the ba gage. In the 68th it was a tradition that the greatcoats were worn over accoutrements. As late as Inkerman during the Crimean War, the 68th, "threw off their greatcoats to get more easily at their ammunition on the field of battle". It seems from period accounts that other light infantry units also adopted this mode of dress.

The May 1812 returns for the 68th note, "the greatcoats are in general bad". By February 1813 they are noted as, "a few greatcoats deficient". Out of 607 men, 377 had new coats just delivered, whilst 230 were still wanted. As this was the last recorded issue till after the war was over, it is presumed the deficiency was made up by using old coats, or the "new" coats of those succumbing to sickness or wounds.

68th (Durham) Regiment of Light Infantry 1814

-

Part 2: Additional Uniform Details

Part 2: Large Color Photo: Mounted Officer (slow: 75K)

Part 2: 68th D.L.I. Display Team (Re-enactment Group)

68th (Durham) Regiment of Light Infantry 1814

-

Part 1: Clothing and Necessities

Part 1: Uniform in Detail

Part 1: Jumbo Color Uniform Photos (monstrously slow: 1MB)

Back to Napoleonic Notes and Queries # 16 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1994 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com