The Cap

The Cap worn by the 68th in 1814 was the second pattern stovepipe shako. The Stovepipe shako had first been authorized in February 1800; the first pattern being made of layers of linen canvas which was then coated with a black shellac lacquer, giving it the appearence of leather. It was replaced by the second pattern in October 1806, "the lackered cap ... has been found from experience to be attended with much inconvenience and prejudice to the Troops ... those Regiments of Infantry which are entitled to caps for the year commencing 25th Dec. 1806 shall have them made of felt in strict conformity to a pattern cap ... the leather parts of which and brass parts are to be supplied once in two years and the felt crown and tuft annually".

This second pattern was made of blocked felt, measuring 7 inches across the top and approximately 7 inches high. At the front was a broad leather peak 21/4 inches at the widest point then tapering to the side. Inside was a linen liner and a two piece sweat band made of patent leather. The two pieces give the appearence of a continuous hatband though this is not the case. There is no evidence to suggest that the stovepipe shako had an external flap. However, the rear inside sweatband might be pulled outside of the cap to act as a neck flap. No chinstrap, was issued with the cap;

Though there is evidence that orders were issued for the addition of chinstraps as occasion demanded. For the Walcheren Expedition 1809,"Lieutenant-Generals of Divisions will immediately give orders that proper means are taken for securing the soldiers caps by fixing tapes so that they may be tied under the chin to prevent them falling off'. As the 68th formed part of the Walcheren expedition, it might be possible that those survivors in the regiment from that campaign continued to use tapes for tying on their caps.

The Shako furniture consisted of a plate, which for light infantry was a bugle horn, a green tuft and a black leather cockade fixed in the centre of which was a regimental button. Green (see sources) mentions, "Green tufts (in the caps ) in place of white ones and bugles in front of our caps instead of plates", upon the 68th's conversion to light infantry in 1808. In December 1814 a circular letter addressed to the Colonel of the 68th stated, "That Regiments of Light Infantry shall in future wear on their caps a bugle horn with the number of the regiment below it instead of the brass plate now in use". This would have been introduced in 1815.

The Stovepipe was officially replaced in March 1812 by the Belgic Shako, which came into general use thereafter. It would appear though, that the light infantry regiments continued to use the stovepipe shako, as did some line regiments where the Belgic Shako failed to reach them. In the 68th the continued use of stovepipes could be put down to problems of supply. According to the inspection return of February 1813, the clothing issue for 25th December 1812 had reached the unit. But as the Belgic Shako had only been approved in March 1812, it is speculative that sufficient supplies could have been accumulated to supply units in the frontline, those in Home Service or destined for foreign duty being equipped first.

Wellington himself might have had something to with the retention of the stovepipe shako. In November 1811 he wrote," I hear that measures are in contemplation to alter the clothing ' caps, etc. of the army ... At a distance or in action, colors are nothing: the profile, and shape of a mans cap, and his general appearence are what guide us ... I only beg that we may be as different as possible from the French in everything. The narrow caps of our infantry, as opposed to their broad top caps, are a great advantage to those who are to look at long lines of posts opposed to each other". So, could Horse Guards have compromised and allowed Wellington to keep some of his units like the 68th in the stovepipe shako.

The Stock

This item was introduced in July 1791 to replace rollers or neck cloths. The stock was made of three pieces of leather and highly polished by use of black-ball. The main piece, made of thick leather went around the front and sides of the neck. At the rear pieces of thinner leather were stitched to it forming tabs. The whole was kept in place by a stock-clasp attached to the thinner leather tabs.

It would appear that a 4inch width was the standard size delivered to units, with the intention that they be cut down to each individual soldiers size upon issue. However as regiments were reminded,"the soldiers stock, which in some regiments is made of such a breadth, as not only uncomfortable to the soldiers, but injurious to his health, by pressing on the glands of the neck, and by that means exciting scrophilous swellings in constitions where there is a tendency to that disorder. The stock, like every other part of the soldiers dress should be adapted to the size and shape of the man". It seems likely that many regiments were not heeding these instructions.

The Jacket

The Jacket

The Jacket worn by the 68th in 1814 had evolved from that first introduced in 1796 to replace the long tailed 18th century coat, athough the use of a jacket had been associated with light infantry and Highland units before this date.

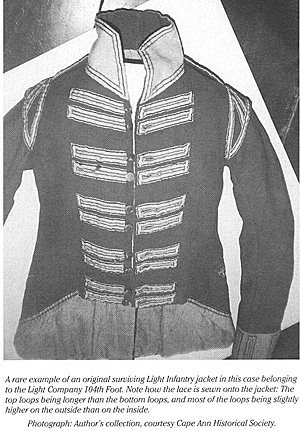

A rare example of an original surviving Light Infantry jacket in this case belonging to the Light Company 104th Foot. Note how the lace is sewn onto the jacket: The top loops being longer than the bottom loops, and most ofthe loops being slightly higher on the outside than on the inside. Photograph: Author's collection, courtesy Cape Ann Historical Society.

The Jackets were originally fairly loose fitting, but developed into a tight fitting garment. So tight did they become that Horse Guards called attention to ". . . the make of the coat, which is in some regiments so cut away as literally to afford no covering or protection to those parts of the body, where warmth is most essential. viz the lower parts of the body and the hip joints, they are moreover made so tight that they are with difficulty buttoned over the waistcoat and they diminish the power of action in a mode highly prejudicial to the health and vigour of the soldier".

The Jacket was made of red wool cloth lined with white serge, the sleeves though being unlined as ordered in 1803. The front skirts were also faced with serge with an edging of regimental lace. The false pocket flap sloped diagonally to the rear whilst the actual pockets were entered by openings in the seams of the pleats at the jacket's rear. The pocket being between the lining and the jackets body.

The cuffs, collar and shoulder straps were made in the facing colour. The collar was to be,"3 inches in breadth" and "to be laced around", though in 1808 the collar height was increased, "in consequence of His Majesties order for the soldiers to wear their hair short (ie. the abolition of the queue). It is his Highness's pleasure that the collars of the Regimental Jackets should be higher in the neck so as entirely to cover the clasp of the stock".

The cuffs were 31/2 inches in breadth with four buttons and four loopings of lace on each. The shoulder straps were made of two pieces of cloth, the underneath of red cloth and the top of regimental facing cloth. The strap was bastion shaped sewn off-set towards the rear and edged with regimental lace.

The description of the 68th's facings vary. The general view of 1802 has the facings being deep green while De Bossett in 1803 mentions Blueish-Green. The pattern of Sir Thomas Trigger's Jacket (the Colonel of the 68th) in Buckmasters Book describes the facings as Dark Green. Hawkes pattern book, page 91, has a 68th Officers jacket with dark bottle-green facings, the same description given by Hamilton-Smiths 1812 Chart.

The most distinct feature of the Jacket was the lace. The lace was about 1/2 inch in breadth to be made of white worsted with distinguishing stripes or worms. For the 68th the lace pattern consisted of red and green worms sewn on in pairs of squared or double head loopings. There were to be,"ten loops of lace on each front of the coat ... the loops to be four inches in length at the top and reduce gradually to 3 inches at the bottom"; though in reality the loops were slightly longer. This produced a tapering effect when viewed from the front.

This tapering effect had originated with the transfer of the lace loops from the lapels of the old 18th century redcoat to the body of the "new" jacket. Though the whole effect became gradually more exagerated. The lace loops were also slightly higher at the outer edge slanting downwards to the centre. There was also four loopings of lace on each pocket flap and "a diamond of lace between the hip buttons over the joining of the back skirts" (though in reality the diamond was a triangle of lace). The 68th being Light Infantry wore shoulder wings made of wool cloth laced around with six darts of lace on each. The wings had a fringe made of worsted wool combed out fine then "steamed", so it rolled back onto itself.

For Light Infantry the buttons were to be small on the whole of the jacket. These being roughly 5/8 inch diameter. There were thirty buttons on the jacket, ten at the front, two for the shoulder straps, four on each cuff, four on each pocket flap and two on the back seams. At the front, "The buttons to be set on equal distances, two and two, three and three according to the order of the regiment", the 68ths buttons being in pairs.

Finally it should be noted that the 68th were nearly clothed in green, a report in 1811 stating, "that the present colour of the clothing for the Light Infantry corps is objectionable, being too conspicious for the service required from them - and that the same objection applies to the belts, which should be black, like those of the Rifle corp. The colour of the clothing is proposed to be green". However, the proposal was never implemented and the 68th along with the other light infantry regiments retained the use of the red jacket.

Trousers Breeches Overalls & Gaiters

The years previous to 1814 had seen the eclipse of the old l8th century breeches and the gradual adoption of trousers for wear by the British Army. Though breeches were still kept for dress or parade wear, it had been realised by Horse Guards that trousers were more suitable for active service, a realization in part forced on Horse Guards by the widespread unauthorized use of trousers by Regiments. Trousers, usually made of linen, had been worn by regiments in the West Indies for some years but the substitution of breeches for trousers in Europe and North America was not experimented with till the Walcheren expedition in 1809. In that same year a circular letter had criticised the adoption of white linen pantaloons in great numbers of Infantry Regiments and Militia.

However, it was not until 1811 that a report stated,"that grey cloth trousers, with a half gaiter of the same, should be substituted for the white breeches and the gaiter now in use ... that these articles form a more convenient dress than the breeches and long gaiters, from leaving the joint of the knee and the calf of the leg unconfined, and are therefore more suitable for marching - the long gaiter from buttoning tight over the calf of the leg being found by experience to produce sores - the grey half gaiter is ... preferable to the black in other respects - the material is more durable - the dye of the latter being injurious to the cloth - and the trousers, when worn out as such, may serve to repair gaiters. The advantage of this dress over the breeches and gaiters seems to be sufficiently proved, from the almost universal use thereof in regs, upon service - it is more easily taken off and put on - it also obviates the use of pipe- clay - and in regard to appearance, it is cleanly, useful and uniform..."

This report was followed by a circular letter of the 29th August 1811 stating, "for the information of the Colonels and C.O.'s of Regiments of Infantry ... serving in Spain and Portugal, that His Royal Highness the Prince Regent, has been pleased ... to sanction the use of long grey pantaloons and short grey gaiters, in the corps serving in those countries, instead of white breeches and long gaiters".

Official approval of the use of grey pantaloons was confirmed and extended in the 1812 Clothing Regulations, when as part of his clothing and necessaries, a soldier was required to have: one pair of grey cloth pantaloons and short gaiters if on foreign service, or if on home service one pair of breeches and long gaiters. By September 1812 pantaloons were being replaced by trousers, a memorandum dated that month reading, "Pattern trousers of grey cloth which are substituted instead of pantaloons for Infantry corps on actual service are this day lodged at the clothing Board".

There was a tendency to wear the pantaloons/trousers on Home service, but this was frowned upon. General Orders 23rd October 1811 declaring that, "the C-in-C will not allow substitution of pantaloons, or any other article of dress, for the regulation white breeches and gaiters, but will allow a loose overall to wear over cloth breeches as preservatives on a march or on night duties". Again, this order was confirmed in the 1812 Regulations.

The 68th would have thus worn the grey pantaloons and trousers during their service in the peninsula, but on their return from France to Ireland (or Home Service) in 1814 would have had to resume the wearing of breeches and long gaiters. However there is speculation whether the 68th or any other returning veteran battalions ever wore the breeches and long gaiters again, but continued to wear the grey trousers contrary to orders, a situation the army was forced to accept by September 1819, when with C.O.'s discreation the "necessary" pair of breeches could be replaced by grey trousers on Home Service. Breeches were finally discontinued in June 1823 when they were replaced by Blue-grey cloth trousers.

Overalls were also kept by the Infantry as part of their necessaries. General Orders 1808 described them as, "Coarse canvas trousers to be worn on marches at night and on duties of fatigue". The overalls were made of Hemp linen canvas also called Russian or Russia duck; this being a particular weight of canvas originally produced in Russia. The 1808 orders for Continental service stated that soldiers were to carry light equipment which did not include the second pair of "necessary breeches".

So with uniform supplies often delayed and clothes often wearing out, the wearing of overalls on active service, or local substitute clothing was resorted to.

The short grey gaiters which came into use in 1811 were made of cloth the same quality as the trousers and jacket. Also the, ". . . Trousers when worn out will do to repair gaiters the price of these gaiters being 2s 3d, the long pantaloons being 7s 6d".

A soldier in the 68th was supposed to have in his possession two pairs of shoes at the price of 6s each. One pair was issued annually with the clothing and is described as a pair of military shoes. The other pair was brought by the soldier as part of his necessaries. General Orders describe the shoes to be carried as, "Two pair of strong shoes, shod with nails or plates at the toes and heels round at toe, and made to come up high round the ankle". High in this case means to fit around the ankle bone like a modern shoe, and not to mean an ankle boot. Ankle boots for other ranks were not introduced into the army until 1823.

The shoes were made on straight lasts although with the advent of the industrial revolution more modern methods of construction were being developed and tested by the army. Most shoes were still made in many small workshops employing a small number of men. The shoes were usually brought by agents who then sold them to the army. Thus a units footwear could, depending on its perambulations represent the work of cobblers from all parts of the British Isles, though by this date manufacturing was beginning to be concentrated in towns like Northampton, Norwich or Leicester.

Earlier military authors such as Cuthbertson had recommended changing the shoes from one foot to another day in day out, to even the wear. In reality most soldiers broke in their shoes to a particular foot. Each regiment had its own cobblers who would repair the mens shoes on the march or in barracks. Even so shoes were nearly always in short supply on campaign, the period memoirs being laced with anecdotes about this. Where severe shortages occured gifts of shoes were made. For example William Brown of the 45th mentions gifts of shoes after the storming of Badajoz and the Burgos retreat.

68th (Durham) Regiment of Light Infantry 1814

-

Part 1: Clothing and Necessities

Part 1: Uniform in Detail

Part 1: Jumbo Color Uniform Photos (monstrously slow: 1MB)

Back to Napoleonic Notes and Queries # 15 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1994 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com