Part 1: Uniforms [AoN13]

Part 2: Campaign Kit and Camp Followers [AoN14]

A short study into campaign kit, camp followers and discipline in Wellington's

Army, as seen from the reminiscences of Peninsular veterans.

A short study into campaign kit, camp followers and discipline in Wellington's

Army, as seen from the reminiscences of Peninsular veterans.

Wellington's army was generally well disciplined. This was largely due to the regimental system. Throughout the war breakdowns in discipline occurred following retreats e.g. Burgos, when the commisariat failed to deliver rations, or when the soldiers had the opportunity to plunder on a large scale e.g. Vittoria and the sack of cities following a siege e.g. Badajoz and Ciudad Rodrigo. Interestingly enough the occasions when large scale indiscipline broke out coincided with the rise in fighting efficiency of the Army.

In order to ensure the maximum state of military discipline 'Wellington pressed for the creation of a Cavalry Staff Corps to assist the Provost marshal. It was argued that the provision of a cavalry Staff Corps would fulfil a dual function,that of police duty and mounted orderlies. Already in existence was an infantry Staff Corps who acted primarily as engineers.'

Wellington was concerned to prevent crime and desertion in the Peninsula army recognising that the Provost Marshal was 'in need of' additional manpower. Experiences on campaign showed the necessity to have a body of selected officers and men of the highest character to enforce discipline on the march, in camp, pick up stragglers, apprehend thieves and protect the local population. Wellington was authorised to raise two troops of cavalry from regiments in the Peninsula. Two further troops were formed in Britain and then sent overseas. Sir George Scovell was given command of the new corps in April 1813.

Peninsula journals do contain references to the Provosts and their work. Private Wheeler of the 51st described how two marauders, one from the 51st and a Brunswicker, attacked two local women. "the cries of the women attracted the attention of the mounted staff, a species of Gendearmes formed of cavalry soldiers ... The two ruffians were made prisoner."

Wellington himself pardoned the soldier from the 51st,

because the 51st had distinguished itself at the Battle of Nivelle

adding the proviso that "he hang the Brunswicker this moment on

that tree." Wheeler noted, "a rope was procured and in a few

seconds the Brunswicker was suspended by the neck to the old

cork tree, and there hung until he was dead."

[1]

Earlier, in the diary of Capt Lawson (Royal Artillery) an

entry for 28 October 1812 states, "A court martial was held

yesterday on Bombadier Nisbett,Gunners Leach, Hall, McKee and

Driver Linton for various irregularities consequent upon their

drunkenness. They plead an order of Lord Wellington's by which a

soldier cannot be punished, who has been in action between the

commission of the crime and the time appointed for the execution

of the sentence. Consult the Adjt. General and I find they are right.

[2]

On November 25, Driver Linton received 300 lashes for

insolence. Lawson records that Gunners Brooker and Canewar

received 500 lashes each but could only enure 325. A gunner who

stole corn was flogged 300. Neglect of duty was punished by 100

lashes (March 1813).

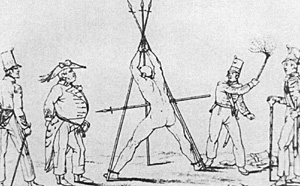

Drummers of the 9th Foot administered the floggings in

April 1813 to the recalcitrants of Lawson's company 8th Btn R.A.

[3]

The Provost-Marshal dispensed speedy forms of justice,

there was no waiting around for the lengthy process of court

martial. Brotherton of the 14th L.D. witnessed the execution of a

Spanish soldier for the theft of a chicken from a French farmyard.

Mitigating circumstances were not taken into account by the

Provost-Marshal "the executioner of military justice." The

Spaniard was hanged as a common criminal.

[4]

Wellington's order that no civilian property in France was

to be despoiled was rigorously enforced. Gleig of the 85th

witnessed the revenge of a Portuguese cacadore on a French

peasant couple. The cacadore's family had been murdered by the

French and he murdered the first French family he came across as

vengeance. He was hanged. Gleig recalled, "no fewer than eighteen

Spanish and Portuguese soldiers were tucked up, in the course of

this and the following days, to the branches of trees."

[5]

When the army was in winter quarters 1813-14, the

ProvostMarshal maintained control. In the memoirs of

quartermaster Sergeant Anton (42nd Regt) a perceptive view of the

provost is revealed. Anton gives a soldiers eye account of the

functions of the Provost, "A provost-marshal was stationed here

(Villafranque) for the more effectually preventing offences and

speedily punishing those who attempted to trespass.

This functionary, though requisite for repressing

delinquencies, is far from being in high repute in the army; his duty

is the most unpleasant in the service, and perhaps in consequence

of this, the one who holds it is generally rewarded, after the

completion of his service as a provost, with the half pay of a

subaltern officer."

[6]

Anton explained that the provost superintended

punishments, ordered punishment of marauders and those absent

without leave. These punishments were "inflicted on the spot, by

the provost's drummer."

Short shift was given to deserters who were apprehended

going over to the enemy. Wheeler (51st) described in a letter

5.9.1811 how deserters were dealt with. First, he described how 9

deserters of the Chasseurs Brittanique Regt. were shot, mentioning

that the 51st had to do more than their fair share of outpost duty

because of the Chasseur's tendency to abscond.

He said, "I wish they were at the Devil or anywhere else,

so that we were not plagued with them ... for if these men were

entrusted on the outposts, more would desert than they do at

present." [7]

Later in the same letter, Wheeler describes in detail the

military execution of three deserters from the Brunswick Oels.

Wheeler rated the Brunswickers as "almost as bad, they too get

many from the Prisons." A square was formed, the firing party of

ten or more men from the culprits own regiment are drawn up only

a few paces from the prisoners. The court martial is read, last rites

administered, then they have made a signal, the firing

party who are ready loaded and firelocks cocked -- watch the

Provost Martial who stands with a handkerchief.

At the first signal the firing party presents, and at the next

they fire. The muzzles of the pieces are so close to the unfortunate

culprits that it is impossible any one can miss the mark, but to

make doubly sure the muzzle of a firelock afterwards is put close

to the head of each as they lie on the ground and discharged."

[8]

Then the army took up positions on the Bidassoa

(Pyrenees) Gleig recalled that "a severe order was issued,

positively prohibiting every man from passing the advanced

videttes, and it was declared, that whoever was caught on what is

termed neutral ground - that is, on the ground between the enemy's

outposts and our own, should henceforth be treated as a deserter."

[9]

Gleig also witnessed an execution. Wellington's view on

punishment was that it should be seen as a deterrent. Flogging, the

most common form of punishment, was seen as a necessary evil.

There were elements within every regiment, the "scum of the

earth" as Wellington termed the minority of hard cases, who

needed the sanction of the lash. Lawrence (40th) received a

sentence of 400 lashes for being absent without leave, he summed

up the painful experience as follows, "it was as good a thing for me

as could then have occurred, as it prevented me from committing

any greater crimes which might have gained me other severer

punishments."

[10]

An opposing view is made by Morris (73rd) "it invariably

makes a tolerably good man bad, and a bad man infinitely worse.

Once flog a man and you degrade him forever, in his own mind; and

thus take from him every possible incentive to good conduct."

[11]

The last comments will be Wellington's. He is quoted as

saying, "it really is wonderful that we should have made them the

fine fellows they are, a fine tribute to the Peninsula army. Years

afterwards he told Lady Salisbury, "I could have done anything

with that army. It was in such perfect order."

[12]

[1] Wheeler p. 148 - 9.

J. Cooke Memoirs of the Late r,war: the personal narrative Capt Cook (sic)

43rd L.I. Regt, 1831 2 vols.

Aspects of Campaign Life

Notes

[2] Dickson manuscripts Vol 4 p.

712. See also Wellington's War p. 271.

[3] Dickson manuscripts Vol 4 p.

719.

[4] Brotherton p. 77-8.

[5] Gleig p. 145-6.

[6] Anton p. 10 1 -2.

[7] Wheeler p. 67.

[8] Wheeler p. 68.

[9 Gleig p. 110, See also p 111-14.

[10] Law rence p. 48-9.

[11] Longford p. 381, also Guedalla

p.205.

[12] Longford p. 381, also

Rathbone p, 297

Sources

G. R. Gleig The Subaltern. A Chronicle of the Peninsular War.

London reprint of 1825 edition.

J. Kincaid Adventures in the Rifle Brigade (1830)

Random Shots from a Rifleman (1835)1981 reprint of 1909 edition.

A. Gordon A cavalry officer in the Corunna Campaign 1990 reprint of 1913

edition.

R.Blakeney A boy in the Peninsula War. London 1989

W. Grattan Adventures with the Connaught Rangers 1809 - 1811. London

1989 reprint of 1902 edition.

Lawrence Autobiography of Sergeant William Lawrence. ed.G.N.Bankes

Cambridge 1987 reprint of 1886 edition.

A. Dickson The Dickson Manuscripts Vols. 1 - 5. ed Leslie Cambridge 1987

reprint of 1905 edition.

T. Brotherton A Hawk at War. The Peninsular War reminiscences of ed B. Perret

Gen. Sir T. Brotherton. Chippenham 1986.

T.Browne The Napoleonic war Journal of Capt. T.H. Browne ed Buckley 1807 - 1816. London 1987

Wheeler The Letters of Private Wheeler 1809 - 1828 ed Hart London 1951.

Tomkinson The Diary of a cavalry officer 1809- 1815. London 1971 reprint of 1894 edition.

J. Anton Retrospect of a Military Life. Cambridge 1991 reprint of 1841 edition.

E.C. Cocks Intelligence Officer in the Peninsula (Tunbridge 1986)

Ed Page Letters and Diaries of Major The Hon C. Cocks 1786 - 1812.

G. Simmons A British Rifleman. London 1986 reprint of 1899 edition.

J. Rathbone Wellington's War. London 1984. W. S. Moorson

Historical Record of the 52nd Regt. London 1860.

Also consulted, P. Guedalla The 3eme. lonon 190.

E. Tongfor Wellington The Years of the Sword. London 1973

Part 1: Uniforms [AoN13]

Part 2: Campaign Kit and Camp Followers [AoN14]

Part 3: Discipline [AoN15]

Back to Napoleonic Notes and Queries #15 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1994 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com