On June 4, 1745 an invading army of 59,000 Austrians and Saxons was soundly defeated by a similar number of Prussians commanded by king Frederick II, near the little Silesian town of Hohenfriedberg. It was a tactical gem that featured a successfully sprung trap, a night march around the Austrian flank, effective use of combined arms tactics, and it established Frederick as one of the great generals of history.

Hohenfriedberg was the coming of age of both Frederick and the Prussian cavalry. The later defeated superior numbers of enemy cavalry on each flank and punctuated its success with the celebrated charge of the Bayreuth Dragoons. Strategically it was not a decisive battle, because the Austrian army proved to be more resilient than it had been in the past, but more importantly, Maria Theresa of Austria refused to give up Silesia.

The Campaign of 1745

The campaign of 1744 had been highly successful from the Austrians' perspective and now seemed to be the opportune time to take back Silesia from Prussia. Marshal Maillebois' French army was retreating back to the Rhine, the Bavarians wanted peace and the Saxons were ready to commit 30,000 troops to fight the Prussians. Even the Russians were making friendly overtures to Vienna and English subsidies had replenished the state treasury. In contrast, the French and Bavarians were broken in spirit and the Prussian army was in a serious state of disrepair following its disastrous campaign in Bohemia in 1744.

The Austrians planned a two-pronged invasion of Silesia in early 1745. General Esterhazy would lead his Hungarian troops and swarms of Croat irregulars into Upper Silesia. There they would attack small outposts, disrupt Prussian communications and supply lines, and advance down the Oder River valley. Esterhazy hoped to draw the main Prussian army towards him while Prince Charles would lead the primary invasion from Koniggratz to Landeshut. There it would join forces with the Duke of Weissenfels' Saxon army and advance towards Breslau. This would cut the Prussian line of communications up the Oder River artery and compel the Prussians to withdraw from Silesia. Simple as that!

On the Prussian side of the mountains, Frederick suspected Austrian intentions to invade Silesia; it was just a matter of determining when and where. Spies reported the Austrian buildup in Moravia. Frederick encamped the main army near Frankenstein, where it could quickly respond to invasions through either the Landeshut pass or the pass through Glatz. ln addition, Frederick posted strong forward detachments at Landeshut (Winterfeldt), Schweidnitz (du Moulin), and Jagerndorf (Margrave Karl). On May 19, 1745 an Austrian captain named von Krummenau defected to the Prussian service for a colonel's commission, and he revealed the Austrian invasion plans to Frederick.

Frederick began to concentrate his forces at once. He sent Zeiten and an escort of 500 hussars south to Jagerndorf to deliver the recall message to Margrave Karl and his 12,000 men. The later left half of his force in the south and hacked his way through endless numbers of Pandours to reach Frankenstein. The Prussian cavalry acquited itself well in this action. Winterfeldt, likewise, had to fight his way out of Landeshut with his 2,000 men before reaching the safety of Schweidnitz.

Frederick defied conventional wisdom by making no attempt to defend the Silesian mountain passes. Instead, he hoped to lure Prince Charles and his army onto the Silesian plain by concealing his Prussian troops in the low-lying ground folds around Alt-Jauernick and Schweidnitz. Spies spread rumors that the Prussians were demoralized and were prepared to abandon Schweidnitz and fall back towards Breslau.

"Frederick has left the mousetrap open; and latterly has been baiting it with a pleasant spicing of toasted cheese." -- Thomas Carlyle

Here, perhaps for the first time, Frederick demonstrated his grasp of strategic tactics, for he knew well that his Prussian army would have the advantage fighting the Austrians in the open as opposed to fighting those annoying small wars with the Croat irregulars in the mountain passes. It appears that the Prussian hussars were better prepared to fight the Austrian irregulars this time, because the Austrian scouts were never able to penetrate the Prussian light cavalry screen prior to Hohenfriedberg and so Charles was not aware that he was marching into Frederick's trap.

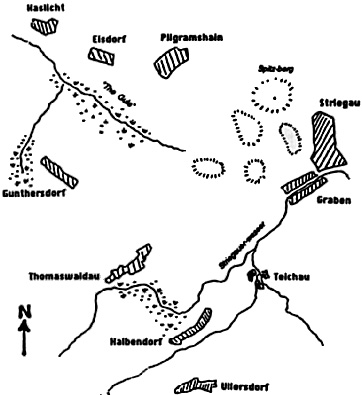

On June 3, 1745 Frederick observed eight columns of Austrians and Saxons descending onto the Silesian plain. They made quite a sight with colors unfurled and their bands playing. They established camp across a four mile front between Kauder in the north and Hohenfriedberg in the south. The Prussians were only nine miles away near Alt-Jauernick and Schweidnitz. The Austrian advance guard took up positions between the villages of Thomaswaldau and Halbendorf (on the Striegauer-wasser). Their Saxon allies held the left flank and posted their advance guard near Pilgramshain. A few companies of Saxon grenadiers, hussars and uhlans occuppied a piece of high ground between Pilgramshain and Striegau known as the Spitzberg.

The Battlefield Terrain

Map 1 illustrates the layout of the terrain over which the coming battle would be fought. The ground is fairly flat and open except for the group of hills to the northwest, behind which is nestled the town of Striegau. The battlefield is bisected by the small Striegauer-wasser which flows diagonally from Hohenfriedberg (off the map) in the southwest to Striegau in the northeast. The ground around this stream is particularly soft and marshy as is a stretch of marshland between Pilgramshain and Gunthersdorf known as "The Gule". Hohenfriedberg is actually two battles. The first battle was fought during the early morning hours between the Saxons on the Austrian left and the Prussian advance guard and right wing. Most of this fighting took place around Pilgramshain and "The Gule" and lasted from 4 A.M. until 7 A.M. The second battle took place between the villages of Gunthersdorf and Thomaswaldau. This action featured the Austrians and the left wing of the Prussian army. It commenced at 8 A.M, and was over in less than an hour. It was in this sector that the Bayreuth Dragoons would win their fame, but more on that later.

Simplified Terrain Map

MAP 1: A simplified plan of the terrain over which the Battle of Hohenfriedberg was fought. The Allied left rested on Pilgramshain and extended towrds Gunthersdorf and was the site of the initial action.

More Hohenfriedberg

- Hohenfriedberg: Introduction

Hohenfriedberg: March and Battle Openings

Hohenfriedberg: Prince Leopold Attacks

Hohenfriedberg: Second Battles vs. Austrians

Hohenfriedberg: Order of Battle

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. VI No. 2 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1992 by James E. Purky

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com