On June 22 four batteries containing 12 heavy guns and 38 mortars opened fire on El Morro from La Cabana, the opening salvo of a deluge that would continue unabated for 39 days. The breastworks began inching forward as the batteries increased their rate of fire on El Morro so that within a week the number of direct hits on it climbed from 200 to about 500 a day. Velasco began losing men at the rate of 30 a day and was forced to spend every night repairing the damage caused by the day's bombardment.

In order to bear the constant fatigue of fighting by day and working at night, he implemented a system of rotating his garrison with replacements from the city every three days. Hoping to take the initiative, he prevailed on Prado to organize an attack against the British siege works and guns. At daylight on June 29th a sortie by 988 grenadiers, marines, engineers and some slaves attacked the works and penetrated to the rear of the British batteries. Although they managed to spike some of the guns, they were repulsed by overwhelming numbers after causing relatively minor damage.

A simultaneous land and naval attack was unleashed on El Morro on July 1st when 4 ships of the line struck from the sea in coordination with a bombardment by land. The ships' guns proved ineffective due to the substantial elevation of the fort above sea level. Counter fire by Velasco with 30 guns from El Morro forced them to withdraw after causing 192 casualties and considerable damage. Although the naval attack was repulsed, the diversion of El Morro's fire against it allowed the British land guns to outnumber the Spanish ones on the landward side until all but three were dismounted.

Just when the besiegers had achieved fire superiority, disaster struck. On July 2nd their breastworks caught fire and in a few hours all of the efforts of the past few weeks went up in smoke. Mackellar considered the fire a serious blow because yellow fever, suffocating heat, and insufficient water had already reduced the army in half. Morale was at a low point from the failure of the naval attack. His troops were hounded by mosquitoes and guerillas sniping at their flanks. The hurricane season was fast approaching, and Velasco was being constantly reinforced from the city without showing signs of weakening. Velasco took advantage of this lull to remount many of his guns, to repair the breaches in El Morro's walls with sandbags and timber and to regain fire superiority.

At this point the battle for El Morro had become a race against time and disease and a lesser opponent might have folded and lifted the siege. Instead, Albemarle decided to redouble his efforts for a final push. New batteries were begun behind the ones burned down. The Navy was ordered to provide the men and supplies needed to continue the siege. The lower deck 32 pound guns of several ships were ordered ashore to create new batteries with seamen replacing the artillerymen lost to battle or disease This cumulative effort slowly reversed the tide so that by July 17th the British had regained fire superiority to such an extent that Velasco's operating guns were again reduced to as few as two, and sometimes none, and he could no longer repair the damage inflicted every day.

With El Morro neutralized, Mackellar was able to push forward again with the construction of the approaches, although the work proceeded slowly because of his troops' fatigue and sickness. There was much anxiety about the failure of the North American troops to arrive and the general consensus held that if they did not do so soon, the siege might yet fail due to the generally weak state of the besiegers. On July 20th sappers, joined by 37 seamen who were former tin miners, began mining the right bastion of El Morro.

The relentless bombardment of El Morro continued. The direct hits falling on it increased to an average of 600 a day. The standing orders to the British mortar batteries were to sustain a rate of fire equal to one shell every three minutes. Velasco began to lose an average of 60 casualties a day as the ramparts were pounded mercilessly. He became aware of the mining and concluded that he was losing the battle of attrition and that his only hope lay in destroying the works closing in on El Morro. He prevailed on Prado to launch another sortie and at 4:00 a.m. on the morning of July 22, 1,300 regulars, seamen, and militia attacked in three columns directed at the approaches, the batteries, and the miners.

After some sanguinary fighting, all attacks were repulsed without any significant damage to the works or to the mining. Mackellar felt particularly relieved. As he later noted, if this attack had been successful it would have been imperative to lift the siege because he no longer had the resources to start anew for a second time.

Perhaps concerned with uncertainty of the outcome and the failure of the American contingent to arrive, on July 24 Albemarle launched a diplomatic offensive aimed at convincing Velasco to capitulate. What followed was a correspondence possible only between 18th Century adversaries. Albemarle wrote to Velasco:

- Sir. It would grieve me as much not to seize the fortress that Your Excellency so heroically defends, as your spirited effort placing you in a position to you lose your life in doing so. I do not fear the first as much as the second since, mindful of the deplorable situation in which Your Excellency finds himself, all satisfaction that would attend the capture of your all but extinguished ramparts would leave my breast if Your Excellency should die within them... To aspire through death to even higher accolades would only usurp your sovereign of so illustrious a captain, and me of the pleasure of meeting You...

I am persuaded that if His Catholic Majesty were witness of Your Excellency's actions since I initiated the siege, he would be the first to order you to capitulate without harboring other object but to preserve such and illustrious and distinguished officer... I hope to make your acquaintance tomorrow and to embrace Your Excellency, for which purpose I ask Your Excellency to draw such articles of capitulation as are suggested by the honour surrounding your person and your garrison.

This eloquent appeal elicited the following reply from Velasco:

- Most Excellent Sir: I promptly answer that which Your Excellency saw fit to address to me this morning, and at the exact time that I promised you I would do so... This castle which it is my fortune defend ... will find me at the head of my troops which, although so inferior in number to yours, I promise shall imitate the constancy of their captain... Do not count me among those who vacillate; there is still much to expect of fortune. I am not in desperate straits, there are still many resources and a long stretch to go before I reach the condition that you ascribe to me. I do not aspire to immortalize my name but to expend my last breath in defense of my sovereign, motivated in this design by the honor of the nation and love of the fatherland... Now finding myself at the time I promised you a reply, and finding only one response possible to Your Excellency's inquiry, I am pained to conclude that in this case it is preferable that the issue be settled by force of arms.

The long awaited first division of 1,983 American provincials and British regulars finally arrived on July 28 providing a much needed boost in morale and manpower. The following day Mackellar completed the mine and all was ready to explode it and storm El Morro. Still, Albemarle made a last attempt to bluff Velasco into surrendering by firing guns and signals to feign an assault. It had no effect. Sensing that the final hour was at hand, Velasco asked Prado for instructions as to how long to resist. The ambiguous reply he received gave him carte blanche to decide. For someone with his fastidious sense of honor this was tantamount to a death warrant to fight to the finish.

However, before resigning himself to the inevitable final assault, Velasco made one last attempt to stop the mine. Ever since it had been known to be in progress there had been disagreement on how to deal with it. As a naval officer Velasco was out of his element in evaluating the nature of the danger facing him. He believed that the rock at the foot of El Morro's bastion was so hard that the mine would not achieve its intended purpose of providing a runway across the ditch. He asked Chief Engineer Balthasar Ricaud and Chief of Artillery Jose Crell de la Hoz to come to El Morro to evaluate what measures could be taken but they discarded the possibility of countermining due to the lack of materials and of skilled miners. Instead, the decision was made to send two schooners and a floating battery armed with 18 pounders to the seaward side of El Morro to attack the miners in the ditch.

This attack was made at 2:00 a.m. on the morning of July 30 but proved unsuccessful after British fire made the schooner withdraw without inflicting any damage.

Luis de Velasco The Siege of Havana, 1762

- Introduction and Background

War Between Spain and England

Plan of Defense and Offense

The Siege

Day of Reckoning

Illustration: Spanish Artillerists 1740 (slow: 76K)

Losses at El Morro: Day by Day 6/22-7/30 1762

Plan of El Morro (slow: 123K)

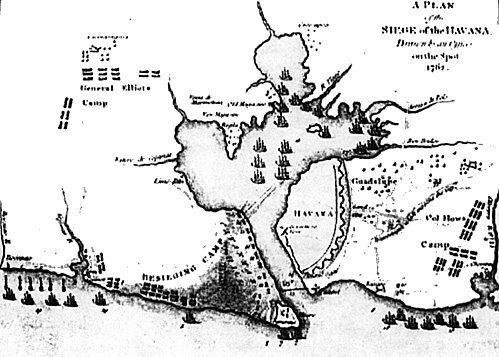

Contemporary Map of Havana (slow: 142K)

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. XII No. 2 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by James J. Mitchell

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com