On the evening of 21 January, Colonel Eyre Coote was at the head of a British army just 7 miles from the Fort of Wandewash. It is unlikely that he was in a good mood for his adversary, Thomas Arthur O'Mullally, a wily veteran in his mid-sixties, better remember as the Comte de Lally-Tollendal, had out maneuvered him.

The Comte had led a substantial force of French and allied native troops against the British held town of Conjeveram, approximately half way between Wandewash and Madras; his aim was to draw British troops away from the fort of Wandewash (to the south west), which had been captured from the French on 29 November the previous year. His plan had worked and the British were left in the wake of the French force, for he managed to turn his force back south without Coote knowing and return to Wandewash were he besieged the small British garrison.

At sunrise on the morning of 22 January, Colonel Coote rode with his cavalry - some 80 European Horse and up to 1200 Native Horse - towards the plain north of Wandewash to reconnoiter the French positions. The rest of his army was ordered to follow. Around 7.00am Coote's advance guard came across a body of Lally's native horse on the plain. The two parties observed each other for a period of time, each safe in the knowledge that help was on its way. As the British watched some 3000 Mahratta cavalry allied to Lally swept east across the plain towards the British position.

The accounts are not terribly clear if the rest of the British force had caught up with their commanding officer at this stage but from somewhere behind his cavalry, Coote managed to deploy a pair of guns. As the Mahrattas charged towards the British position, the British and Native Horse wheeled to either flank, revealing the two guns which fired upon the charging horsemen at point blank range. The effect must have been devastating for the Mahrattas immediately fled "with heavy loss."

Contact

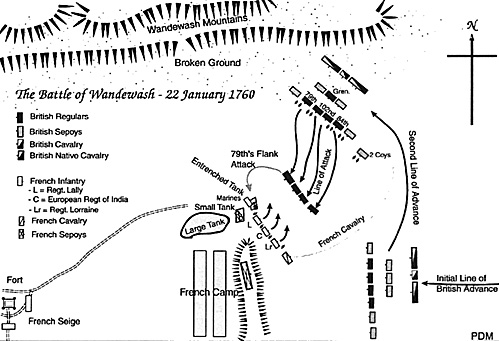

Coote continued his advance towards Wandewash and found the French army set out in two lines, approximately 2 miles to the east of the fort, facing eastwards. Their left flank was covered by a large water tank . In advance of the left front was a smaller dry tank which had been fortified and armed with 4 cannon. The cannon commanded the whole of the plain to the front and would allow the French to pour enfilade fire into the British if they attempted to close with the French lines. To the rear of the right flank was a low hill ridge which concealed both the French encampment and the siege works around the fort from the British view. Approximately 900 French trained Sepoys were deployed on the ridge.

Leaving his advance guard of cavalry, the British commander returned to the main body of his army, deployed it into 2 lines, advanced it towards the French camp and halted. Lally did nothing! After a pause, Eyre Coote turned the British force to the right and filed the whole contingent across the front of the French towards the Wandewash Mountain some 2 miles away to the north.

As the leading columns reached the broken and stony ground close to the foot of the mountains, Coote halted the advance and faced the enemy at a distance of approximately 1 1/2 miles. Once again, his maneuver was either ignored or not noticed by Lally so Coote decided to continue his advance along the stony ground past the French left flank.

His plan was simply to outflank the French deployment by moving to a position opposite the fort. This way he would gain communications with the garrison, use the mountain to protect his left flank (several accounts of the battle describe this stony ground as impassable to cavalry) whilst his right would be given covering fire from the fort. This would then let him threaten Lally's flank and rear.

By now the French were on the move as Lally had the option of remaining in his prepared positions and being out flanked by his adversaries or leaving his positions and trying to bring the British force quickly to battle. Seeing the French troops and their allies dressing their ranks – and most likely being near enough to hear the sounds of orders being shouted amidst the beat of the drums - Coote halted his force on the broken ground that formed the lower slopes of the mountains. The British force faced left to form a line of battle obliquely to the enemy.

The French Commander had little option but to wheel his whole line, using the fortified tank as a point of pivot, so that his right flank came forward and his troops – in a single line - were parallel to the British position. They had changed their facing from east to northeast (see map).

On the extreme right flank of Lally's force were 300 "European" cavalry, next to them was the Regiment of Lorraine comprising of 400 men and to their left were 700 men of the European Regiment of India (Compagnies des Indies). Next came Regiment Lally in their red coats, a striking contrast to the off-white coats of rest of the French force and their native allies; the regiment had its left flank up against the entrenched tank which was manned by marines from the French fleet and 4 cannon. The French had 16 guns in all: 4 in the entrenched tank, 3 guns either side of Regiment Lally another 3 between Compagnies des Indies and Regiment Lorraine and 3 more between this regiment and the "European" horse.

To the rear of the entrenched tank was another small tank held by 400 Sepoy infantry and on the far right flank, on the hill ridge in front of the French camp, another 900 Sepoys. The overall force amounted to 2250 French infantry and cavalry and 1300 Sepoys. There were another 500 French and native troops left to man the batteries before the walls of the fort at Wandewash. The 3000 Mahratta horse were keeping well out of the way of the British, having already had cause to regret their actions earlier in the day.

Deployment

Eyre Coote's force was deployed in 3 lines:

- First Line: 4 British Regular battalions and 2 Sepoy battalions (from British right to left): Sepoys (850 men), Drapers - Regiment 79th of Foot (400 men), 2 weak battalions of The Queen's Own Royal Volunteers – 102nd Regiment of Foot (Other accounts suggest this may be 2 East India Company Battalions of 400 men each), Coote's Regiment – 84th of Foot (400 men), Sepoys (850 men), 3 cannon were positioned in the gaps to either flank of the 79th and 84th, and a further 2 cannon were detached a little in advance and to the left of the line, supported by 2 companies of Sepoys.

Second Line: Sepoys (200 men), Grenadiers (300 men) and gun, Sepoys (200 men)

Third Line: One account suggests that there may have been as few as 370 Native Horse whilst Fortescue states 1250. Native Cavalry, European Cavalry (80 men), Native Cavalry

The total force was 1980 Europeans, 2100 Sepoys, up to 1250 Native Horse and 16 cannon. The latter figure taken from Fortescue means that there was an extra cannon somewhere, as I can only account for 15.

Into Battle

The British did not delay their advance but, when they were within three quarters of a mile, Lally led his 80 European cavalry on a wide sweep across the grassy plain to attack the British cavalry in the third line. Coote's native cavalry broke immediately and fled before the French could reach them. This was a critical moment in the battle, for as the Sepoys on the British left flank started change their face to meet the attack they started to waver. Only the British horse stood their ground. The moment was saved by the 2 cannon and Sepoys to the front left of the British, who under a Captain Barker advanced to close range of the French hussars and fired. The effect was bloody and immediate; between 10 and 15 men and horses fell at the first shot and the cavalry broke despite Lally's best endeavors to rally them. They eventually rallied once they had returned to the rear of the French positions.

During the cavalry attack the French artillery opened fire "wildly and unsteadily" with grape on the halted British infantry who were only just within range for roundshot. Coote gave the order to advance and the Redcoats obliged whilst the British artillery traded shots with the French. It must have been effective for Lally, seeing his men to be impatient to move from the 'destructive fire', placed himself at their head and ordered an advance.

Eyre Coote ordered the second and third lines of his force to halt and advance to meet Lally with his first line only. It was his intention to stake everything on the defeat the French regular troops. Despite the outbreak of musketry by the French his men were ordered to save their fire until they could give a close range volley. Some of the native troops mixed into the British ranks started to fire at whim and it was only with the greatest of discipline imposed by the officers and NCO's that the disorder was prevented from spreading down the whole line.

Coote himself was seen to gallop from one flank of the line to the next, issuing orders as he went. The Colonel actually had three musket balls pass through his clothing. Once discipline had been restored he moved to a position to the left of his own regiment.

By 1.00pm the crack of musket fire had become commonplace and powder smoke hung across the battlefield in the hot sun. Average temperatures for the time of year would be 77°F or 25°C.

Coote's Regiment had exchanged 2 volleys with the Regiment Lorraine when Lally formed the regiment into a column 12 men wide and ordered that they charge the British line with bayonets.

One eyewitness account states: "Lally himself was always seen sword in hand where danger was greatest." Coote waited until the column was 50 yards away and then fired a devastating volley that ripped the front and flanks of the charging Frenchmen to tatters. Undeterred, Lorraine pressed the charge home faster and hit the 84th at the run. Vicious hand-to-hand fighting broke out momentarily until the weight of the column broke the line to its front. The regiment was broken in two for just 3 minutes, but not in flight for the rest of Coote's regiment broke ranks and attacked both flanks of the column.

Lorraine, already smarting badly from the deadly 50-yard volley became confused and ran back to their camp with the 84th hard on their heels. The French Sepoys were demoralized and with their apparent reluctance to face the 84th Coote used the hiatus to order his regiment to reform; he then rode to the right flank to check how Draper's Regiment was coping.

As Colonel Coote rode hard to dodge the French shot there was a bright flash of light to his front left followed by roar of a large explosion, which could be heard above the hubbub of battle. Coote could see a dense cloud of smoke rising from the rear of the entrenched tank.

Fortuitously for the British, a shot from one of their guns had hit a French tumbrel full of gun powder and the ensuing explosion killed or disabled 80 men and killed the commander of the entrenchment. Those marines lucky enough to still be alive abandoned the position and fled toward the French right, leaving the guns behind. Seeing this the Sepoys in the small tank to the rear also routed from their position.

Seeing the disorder of the French Coote urged his horse on towards the 79th where he ordered Major Bremerton to advance on the French left and seize the entrenched tank. The 79th closed quickly on the position with Major Bremerton at their head.

The French left was commanded by the Marquis de Bussy, he ordered Lally's Regiment forward to threaten the flank of the 79th "forcing them to fetch a compass and file away to their right." This bought de Bussy some time and he managed to rally some of the routing marines and Sepoys and to reoccupy the entrenched tank with 2 platoons.

The British troops reached the tank before de Bussy could complete his dispositions and the 79th swept down the north face of the tank and chased the two French platoons back out.

In the assault on the tank, Major Bremerton was mortally wounded. His men wavered momentarily but the Major called "Follow, Follow! Follow your comrades and leave me to my fate." Bremerton died shortly after.

Major Monson took command of the regiment, and the 79th advanced "with increased ardor and fury". Up the southern side of the tank they ran and as they cleared the parapet they opened a devastating fire on the gunners who were working the three guns posted between the tank and Lally's Regiment, driving them from their guns.

De Bussy was in a difficult position with the 79th close on his flank and more British advancing to his front he had to act fast. He ordered Lally's to wheel to the left to prevent enfilade fire from the 79th and detached two platoons to flank British force by advancing on the western side of the tank. He had misread the temperament of his men for they shrank from the well-disciplined fire of the British and refused to move into close quarters. Whilst maintaining a steady rate of fire against the 79th, neither the men nor de Bussy were aware of the two guns until they opened fire at close range upon the regiment's right flank.

In a last ditch effort to save the day, de Bussy led his men in a charge against the southern face of the tank; his horse was shot from beneath him and on looking around he discovered that only twenty men had followed him. Two platoons of the 79th doubled around to cut de Bussy off from what remained of Lally's regiment. Some Grenadiers from the second line had advanced to support the attack and they escorted Major Monson to De Bussy, who surrendered his sword. The whole of Lally's regiment was captured or dispersed.

In the French center the European Regiment of India had maintained a long-range exchange of musketry but, having found that both flanks were exposed, faced about and retreated in good order.

By two o'clock in the afternoon the battle was over.

Comte Lally de Tollendal had ordered the Sepoys on the ridge to advance but they had refused to move and the Mahratta horse withdrew from the area when they saw how things were progressing. For Lally, nothing was left of his army but for the squadrons of French horse which advanced to cover the retreat. On their appearance a few men of the Regiment Lorraine rallied and harnessed teams [of oxen or horse the sources do not state] to three field guns and helped the cavalry cover the retreat.

As the British cavalry were too weak to attack and Coote's native horse refused to face the French cavalry, Lally was able to set fire to his camp and collect his men from the siege batteries at Wandewash and retire.

The news of the British victory reached Bombay on 1 March. Cadet Gunner James Wood recorded the news of the battle in his diary: The same evening a patamar arrived from Madras with the joyful news that the English had defeated the French under the command of General Lally on 21 January 1760, the English under the command of Colonel Coote. It is said the French had 2100 Europeans, 300 Cofferees, 8000 Sepoys besides cavalry and 25 pieces of cannon; the English had 1700 Europeans including cavalry, 3000 Sepoys, 14 pieces of cannon and one howitzer. After a smart engagement for two or three hours the whole French line gave way and fled under cover of their own cannon imagining we should pursue them. They had about 800 men killed and wounded, General Bussy being taken prisoner; the English lost in the field 86 killed and about 150 wounded: amongst the former was Major Brereton. We took in the field 22 pieces of cannon and great quantity of their baggage.

On the success of this battle the English laid siege to Chittapet and took the whole garrison prisoners of war and took the Chevalier De Tilley. Timery was reduced. From thence they went to Arcot, the capital of that province, laid siege and took it in a few days in which were 200 Europeans and 300 Sepoys, 20 pieces of cannon and 4 mortars so that the English are now masters of the Coromandel coast, and the French troops have nothing to take care of but their own garrison at Pondicherry which they are putting in the best order they can. On the information of the above news which arrived at 6.30pm, a Royal Salute of 21 pieces of cannon was fired from the fort.

Conclusion

Coote had shown an extraordinary degree of determination to bring Lally to battle and shown himself to be a good tactician. He was obviously fortunate to have good officers and disciplined troops under his command but he forced Lally to move from prepared positions that gave the French the advantage. One may ask how things would have fared if Coote had not had the early morning encounter with the Mahratta allies of the French; what if the Mahrattas had joined the battle later in the day?

As for Lally, perhaps he was starting to lose some of his thirst for battle that had been so evident in his youth. It would seem that he was frustrated in his tasks and often found them "heart-breaking due to the ignorance and incompetence of his officers."

The obstinacy of the Council at Pondicherry aroused in him a fierce anger that caused him to choke with rage and indignation. "Let them delay in sending me supplies and money and I will harness them to wagons and flog them like mules". A sentiment anyone who works in a large company with a purchasing department can relate to!

Bibliography

Fortescue; History of the British Army Vol. II, 1899

James Grant; British Battles on Land and Sea, 1878

Mike Kirby; The Campaigns in India During the Seven Years War, 2000

Tom Pocock; Battle for Empire

Victor Surridge; Romance of Empire - India, 1900

James Wood RA, Ed Whitworth; Gunner at Large, 1988

More on India

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. XI No. 3 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 by James J. Mitchell

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com