This article stems from an innocent question from SYWA member Mike Kirby. "Do you know the village of Rockbourne in Hampshire?" I confirmed that I did and said that I had actually lived in the next village during the 1980's. Mike then persuaded me that what I really wanted to do was help him with a bit of research for his forthcoming book on the "Campaigns in India During the Seven Years War," by making a trip to Rockbourne Village Church. It transpired that during his research Mike had found some references to the Regimental and King's Colours of the 84th Foot being taken to the church by Eyre Coote after the Seven Years War.

This article stems from an innocent question from SYWA member Mike Kirby. "Do you know the village of Rockbourne in Hampshire?" I confirmed that I did and said that I had actually lived in the next village during the 1980's. Mike then persuaded me that what I really wanted to do was help him with a bit of research for his forthcoming book on the "Campaigns in India During the Seven Years War," by making a trip to Rockbourne Village Church. It transpired that during his research Mike had found some references to the Regimental and King's Colours of the 84th Foot being taken to the church by Eyre Coote after the Seven Years War.

I contacted the local Vicar, or more precisely his wife, to see if there were any Church records about the two standards being kept at the Church and to establish what had happened to them. I was quite excited by the response I got: "Oh yes," said the lady on the telephone, "there are a couple of old flags at the back of the church. Can't say that I know much about them."

A weekend excursion was hastily arranged - with a suspicious family in tow! To my surprise the church really does have the colors and there is a large copy of an oil painting of Eyre Coote - the original portrait is in the National Portrait Gallery in London - as well as a memorial tablet.

So who was Eyre Coote, what sort of man was he and why was he so important to the British cause in India during the Seven Years War?

Eyre Coote

Born at Ash Hill, Kilmallock, County Limerick in 1726, Eyre Coote entered the army at an early age: he was gazetted as a subaltern in Blakeneys Regiment of Foot (27th) in 1744. Reportedly a brave and conscientious soldier, he was one of several keen young officers who rose under the eye of Pitt and the Duke of Cumberland.

He served against the Pretender in the '45, but was Court Martialled after the Battle of Falkirk (17 January 1746) for having broken the 14th Article of War. Falkirk was the last Jacobite victory of the '45 Rebellion; 8,000 Rebel Highlanders under the Young pretender broke the British line of 8,000 troops plus 1,000 Campbells under General Hawley. The British were driven from the field with a loss of 600 killed, 700 captured along with all their baggage as well as 7 guns. The rebels lost just 120 men.

The Articles of War Section XIV ART. XIII, states: "Whatever Officer or Soldier shall misbehave himself before the Enemy, and run away, or shamefully abandon any Fort, Post, or Guard which he or they shall be commended to defend, or speak Words inducing others to do the like; or who, after Victory, shall quit his Commanding Officer, or Post, to plunder and pillage; every such Offender, being duly convicted thereof, shall be reputed a Disobeyer of Military Orders; and shall suffer Death, or such other Punishment as by a General court-martial shall be inflicted on him."

Eyre Coote was fortunate to be found Not Guilty of Cowardice; he was however found Guilty of Misbehaving by going to Edinburgh with the Colours, which he had carried during the battle. As punishment he was cashiered from the Army, but due to his influence at Horse Guards and with Cumberland, this sentence was eventually (and surprisingly) quashed. However, it would have left his reputation under a cloud, and this may account for the intensification of his determined nature and natural ambition pushing him to even greater extremes as a way of living down the disgrace in future years.

In 1749, he exchanged as a Lieutenant into the 37th Regiment of Foot (North Hampshire) and served in Minorca. His Return to England on leave in 1752 is the last information I can find until he transferred to the 39th Regiment of Foot (Dorsetshire) in 1755 and was Gazetted Captain. He then sailed with 2 companies of the 39th to serve in India, where he distinguished himself between 1756 and 1758 in the campaign against Surajah Dowlah and the French in Bengal.

He played an important part at the battle of Plassey (23 June 1757), but Robert Clive had come to dislike him. In this there may have been jealousy, but it is most likely to stem from the way that Coote treated Honorable East India Company troops. A good example is that on 2 January 1757 Coote refused to allow Company Sepoys to enter Fort William (Calcutta) because he had orders not to relinquish command of the fort. He threatened to arrest the officer commanding the Sepoys, who was under the direct command of Robert Clive. Clive personally intervened and said that he would arrest Coote unless he was given command of the fort. The matter was eventually resolved - on the face of it - to the satisfaction of all concerned, but this may have prompted Clive's dislike of Coote.

Over the months and years, Clive frequently wrote letters of complaint to Coote, yet his letters of response were answered with dignity and forbearance - never once saying anything with which a senior officer could take offence or exception. However, Coote was greedy, even by Indian standards; he also had an ungovernable temper, yet he was heroic and persistent in conditions which soon took their toll of weaker men.

Having returned to England, he was gazetted Lieutenant Colonel and on 10 January 1759 Parliament confirmed the rank and ordered him to raise his own regiment of foot, the 84th. That year he took the regiment to India, to fight the French in the Carnatic region in the south east of the sub-continent.

By the summer of 1759, Robert Clive's health was failing and relations with the neighboring Dutch flared up to open conflict. Clive appointed Colonel Francis Forde to command the British troops in Bengal. This was something with which the Company Directors were unhappy, and Eyre Coote was placed in command of all British troops in India. Clive was furious when he heard the news. "I tremble to think of the fatal consequences of such a mercenary man as Coote commanding here," he said, "for God's sake keep him on the Coast [The Carnatic], there he can only get a little drubbing, but here he may ruin the Company's affairs for ever."

Victory

It was of some consolation to Clive that Coote did stay on the Coast but, instead of getting a "little drubbing," Coote defeated the French, under the Comte de Lally-Tollendal, at Wandiwash on 22 January 1760. Clive learned news of Coote's great victory as he left Calcutta bound for England. He was most likely mortified.

Coote had written to Clive on hearing that he was due to return to England, "I always was a sincerer friend of yours than you were led to believe."

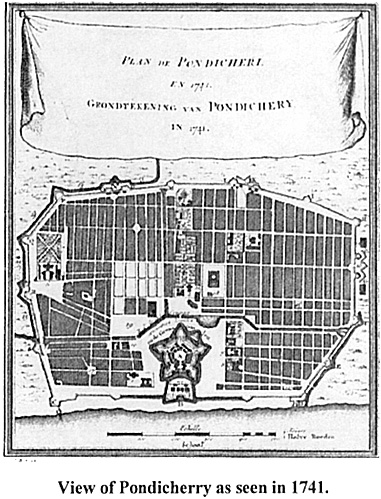

These words would suggest that others had been poisoning Clive's mind against Eyre Coote and, because of this, he never relented in his animosity. It was Coote's siege and ultimate capture of Pondicherry on 15 January 1761 that completed the discomfiture of Lally and the ruin of the French cause in India. What this meant to the French can be guessed from the fact that Lally was afterwards tried for cowardice and executed.

In 1761 Coote left Madras for Calcutta and became a diplomat, a role that he did not like and was almost certainly not suited for. He undertook this duty until 1762, when he returned to England by way of St. Helena. In St. Helena he met and married the daughter of the Governor, Miss Susanna Hutchinson, and on their arrival in England took the lease on West Park, Rockbourne, in the County of Hampshire. Assumedly, this is when he brought the Regimental and King's Colours with him for the regiment was disbanded in 1764.

In 1770 he became a K.B. and returned for a short time to India, only to quarrel violently with the Madras Council over the precise area of his authority and to return after six months. Warren Hastings then wrote: "God forbid that he should ever return." But when he came back, in January 1779, once more commander-in-chief with a seat on the Council of Bengal, he was given wide powers. Hastings faced a grave crisis when he was confronted by the Maratha Confederacy. The fight against the Maratha princes prospered, but when the Madras government incited Hyder Ali to war again, in 1780, Hastings sent Coote himself to take command in the Carnatic to save Madras in the hour of peril. Hastings was both magnanimous and energetic. Coote was given a field allowance of £18,000 a year and discretion to campaign as he wanted. Gold, rice and bullocks were got by all possible means to maintain Coote's army in the hot, barren plains around Madras. Coote was short of cavalry and tents; supplies reached him by sea from Bengal and the French were active off the coast.

He himself was suffering acutely from the climate. He showed no great strategical insight, but his toughness inspired the Sepoys and kept his army in the field. He was rewarded by two victories against Hyder Ali and the Frenchman Bussy, at Porto Novo in 1781 and at Arni in 1782.

In the latter year he suffered a stroke. In April 1783 he was struck down with paralysis and died at Madras. Peace was made with Mysore in the following year. The victories in India were small and unspectacular in the public eye, but they helped to counterbalance the loss of America.

In conclusion, Eyre Coote was not a particularly agreeable man: he had old-fashioned views about his native troops--"the blacks"--and he quarreled with just about everybody. He was generally agreed to be avaricious, but he was also ready to die in his saddle and his determined nature and fighting spirit did much to save British India.

More on India

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. XI No. 3 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 by James J. Mitchell

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com