Phase One – Ambush and Reversal of Fortune

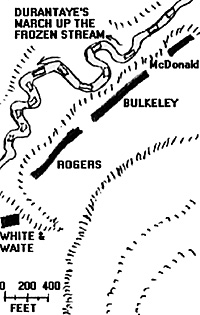

Around a mile south of their intended destination, the rangers of the advanced guard spotted Durantaye's party approaching. They were marching southward on the frozen surface of Trout Brook and heading on a path that would take them directly across the front of Rogers' ambuscade, exposing their left flank to his hidden troops.

Around a mile south of their intended destination, the rangers of the advanced guard spotted Durantaye's party approaching. They were marching southward on the frozen surface of Trout Brook and heading on a path that would take them directly across the front of Rogers' ambuscade, exposing their left flank to his hidden troops.

Word was sent to Rogers who ordered his men to drop their packs and prepare for action. Although the weather was cold, many of the men, including Rogers, shed their outer coats so as to free themselves of any impediments. Things would be hot enough presently. Rogers ordered his men to descend to the edge of the brook and face left. They would fire on his signal. When the front of the enemy column was nearly opposite the far left of the line of rangers, Rogers' men fired a ragged volley into them. Accounts differ as to the casualties inflicted on the surprised French. Rogers claimed that forty fell dead. French accounts claim no more than a half dozen or so were hit. Nevertheless the survivors, startled and disorganized by this event, withdrew quickly back whence they had come.

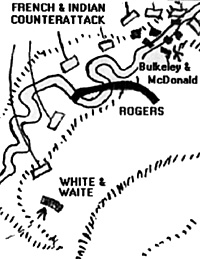

Captain Bulkeley lead his division in pursuit of the fugitives as the remainder scalped the fallen. Some fifty yards further on, as Bulkeley's men rounded a curve of the river, a massive volley of musketry sent nearly fifty of them to their maker. Langy, having heard the initial fusillade, had formed his men up into a crescent-shaped line and now exacted a sanguinary revenge on Rogers' men.

Phase 2 – Pursuit

Within minutes Langy's force had united with the survivors of Durantaye's force. The triumphant rangers had run straight into Langy's close range volley. The surprise was total. Captain Bulkeley and all his officers were either killed or wounded within minutes. Although mortally wounded, Lieutenant Moore and Ensign MacDonald were able to rally the survivors and fall back to Roger's main body before they died. They were closely followed by Langy and Durantaye. All Rogers could do was to shout to his men to fall back up the slope and take cover. If they could hold out until nightfall, they might be able to disperse and save themselves.

Within minutes Langy's force had united with the survivors of Durantaye's force. The triumphant rangers had run straight into Langy's close range volley. The surprise was total. Captain Bulkeley and all his officers were either killed or wounded within minutes. Although mortally wounded, Lieutenant Moore and Ensign MacDonald were able to rally the survivors and fall back to Roger's main body before they died. They were closely followed by Langy and Durantaye. All Rogers could do was to shout to his men to fall back up the slope and take cover. If they could hold out until nightfall, they might be able to disperse and save themselves.

Langy's and Durantaye's men pursued the rangers with a vengeance. Enraged by the sight of their scalped comrades, they tomahawked any enemy wounded or stragglers they encountered, giving quarter to none. The rear guard of the Rangers, although on Rogers' side of the brook but separated from his main body, was cut off and nearly surrounded. Of these men only Ensign Waite and two privates were able to escape the circling enemy troops.

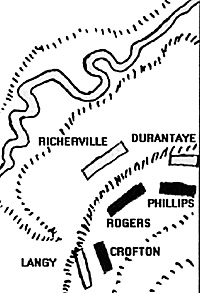

The surviving rangers who had withdrawn up the slope under Rogers, now probably numbering no more than 130 men, posted themselves behind what trees, boulders, or undulations of terrain best lent themselves to defensive shelter. From cover they were at last able to lay down a defensive fire adequate to slow the enemy advance. Nevertheless they were hard pressed and, in a fighting withdrawal, which eventually lasted some forty-five minutes, they suffered another fifty to sixty casualties before the fighting temporarily died down.

Phase 3 – Final French and Indian Thrust

The French and Indians took advantage of this lull in the fighting to reorganize themselves and prepare a plan of attack. With Durantaye taking the French left, and Cadet Richerville, the center, Langy would take his men and try to sweep around the right.

Durantaye was attempting to outflank Rogers' right. To counter this, he sent Ensign William Phillips with eighteen men to counter this threat.

The French and Indians took advantage of this lull in the fighting to reorganize themselves and prepare a plan of attack. With Durantaye taking the French left, and Cadet Richerville, the center, Langy would take his men and try to sweep around the right.

Durantaye was attempting to outflank Rogers' right. To counter this, he sent Ensign William Phillips with eighteen men to counter this threat.

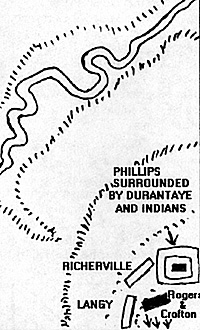

In response to Langy's similar effort against his left, Rogers sent Lieutenant Edward Crofton with fifteen up the hill's southern slope. To plug the resultant gaps in his overextended line, he once again ordered his men to withdraw uphill. As Crofton's party got into a hot engagement with Langy's flanking party, Rogers was induced to send another ten men to this endangered flank. His center now numbered no more than thirty men. A full ninety minutes had now elapsed since Bulkeley's force had been counterattacked at the brook. With his center caving in and ten more of his men shot down, Rogers ordered both flanks to retreat up the hill.

Phillips was in extreme duress. Cut off from the rest of the rangers and completely surrounded, he was negotiating with the enemy for quarter. He called out to Rogers that his command was finished and would either surrender or fight to the death. Upon this disheartening news Rogers fled with his survivors to Crofton's men, where he ordered everyone to disperse, each taking a different route back to the appointed rendezvous point for the evening. As Phillips' men surrendered or were cut down, Rogers' and his surviving rangers melted into the darkening forest and ran for their lives.

Aftermath

By all accounts, the "Battle on Snowshoes" was an unmitigated disaster for Rogers and his men. It took him two days to return to Fort Edward. Of a total command of 184 men, 125 had been killed in the battle and four more would die of their wounds back at Fort Edward. The dead officers included Captain Bulkeley, Lieutenant Moore, Ensign McDonald and ten other officers and sergeants. Also killed were four of the regular volunteers who had accompanied the rangers. Phillips was captured as were two British volunteers, Capt. Pringle and Lieutenant Roche, who turned themselves in to the French after wandering for several days in the wilderness with Rogers' own servant, who, claiming erroneously to know the area, had eventually lost his mind, wandered off, and died of exposure.

By all accounts, the "Battle on Snowshoes" was an unmitigated disaster for Rogers and his men. It took him two days to return to Fort Edward. Of a total command of 184 men, 125 had been killed in the battle and four more would die of their wounds back at Fort Edward. The dead officers included Captain Bulkeley, Lieutenant Moore, Ensign McDonald and ten other officers and sergeants. Also killed were four of the regular volunteers who had accompanied the rangers. Phillips was captured as were two British volunteers, Capt. Pringle and Lieutenant Roche, who turned themselves in to the French after wandering for several days in the wilderness with Rogers' own servant, who, claiming erroneously to know the area, had eventually lost his mind, wandered off, and died of exposure.

The French, on the other hand, despite Rogers' claims of having killed many more, only admitted to figures ranging from four killed and twenty-two wounded, to ten killed and eighteen wounded. Although Captain d'Hebecourt, in a letter to Colonel François de Bourlamaque, implied that the French casualties were high, he gave no specific numbers.

Major Rogers' relationship with Colonel Haviland, never good in the best of times, was not helped by this defeat. Although the strength of the rangers was seriously diminished, they were soon rebuilt and continued to be Great Britain's best bet for irregular warfare for the remainder of the conflict. Unfortunately Rogers' methods of leadership never set well with his superiors with whom he repeatedly clashed. His inability to deal with authority probably contributed to the Crown's reluctance to reimburse him for numerous expenses he incurred in outfitting his men out of his own pocket. Plagued by debts and hounded by creditors, Rogers eventually turned to the bottle for succor and died in obscurity in England years later.

More Battle on Snowshoes 1758

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. XI No. 1 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by James J. Mitchell

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com