For many French & Indian War aficionados, one of the most well known units was the body of rangers raised by Robert Rogers. Organized as a form of light infantry and intended to beat the French and their Indian allies at their own game, the rangers had a checkered career at best. Loathed by most regular British officers, to say nothing of the rank and file, for their non-regulation clothing and lax discipline, the rangers were nonetheless considered an invaluable adjunct to the British army for their scouting and skirmishing abilities and in the absence of anything better.

For many French & Indian War aficionados, one of the most well known units was the body of rangers raised by Robert Rogers. Organized as a form of light infantry and intended to beat the French and their Indian allies at their own game, the rangers had a checkered career at best. Loathed by most regular British officers, to say nothing of the rank and file, for their non-regulation clothing and lax discipline, the rangers were nonetheless considered an invaluable adjunct to the British army for their scouting and skirmishing abilities and in the absence of anything better.

Braddock's disastrous defeat at the Monongahela in 1755 had underlined the British army's weakness at fighting in the woods against irregulars, a weakness which had been hinted at as early as 1745 at Fontenoy when a force of 900 Arquebusiers de Grassin utterly paralyzed an entire brigade of regular foot under Brigadier General Ingoldsby. Thus, in the early months of the war in North America, a call went out for soldier volunteers familiar with backwoods fighting to form a series of ranging companies. Of all the ranger battalions formed, that of Robert Rogers is the most famous.

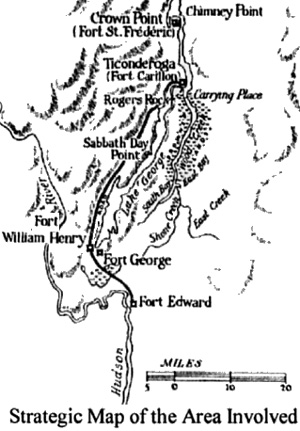

In the Spring of 1758, the war between the British and French in North America was entering its fourth year, hostilities having been first begun in 1754 by an ambitious young Virginian named George Washington. Despite their overwhelming superiority in numbers, things had not been going all that well for the British. Although early in the war they had been fortunate enough to seize forts Beausejour and Gaspereau in Acadia and had even defeated an army of French regulars and captured their commander at Lake George in 1755, other operations had come to naught.

Braddock, the first British commander-in-chief, had been killed and his army ruined at the Monongahela in 1755. In 1756, the only British base on Lake Ontario had been captured by the new French commander, the Marquis de Montcalm, after a brief siege, and an auxiliary fort situated at the Oneida Carry that guarded communications to and from points west of the headwaters of the Mohawk river, Fort Bull, had been taken by assault, its garrison massacred, and the fort itself left in ruins by the excellent colonial marine officer Gaspard Joseph Chaussegros de Lery.

Finally, the glorious British victory of Lake George in 1755 had been avenged in August of 1757 by Colonel Munro's surrender of Fort William Henry to General Montcalm.

View to a Kill

It was against this precarious background that the ranging companies were formed and employed with a view to disrupting enemy communications, destroying their supplies, providing intelligence of enemy movements, and taking an occasional prisoner. Although rarely as effective as the French scouts or their Indian allies, the rangers were nevertheless a vital element in the British war effort.

In the cold and wintery month of March of 1758, a body of some 180 rangers under the command of one Captain Robert Rogers encountered the French on the mountainous slopes south of Fort Carillon (modern-day Ticonderoga). What ensued was a desperate and bloody struggle that has since been immortalized by the name of the "Battle on Snowshoes." First let's hear the story as told by Rogers himself:

"March 10, 1758, I was ordered by Col. Haviland to the neighborhood of Ticonderoga, not with 400 men, as was at first given out, but with 180, officers included. We had one Captain, one Lieut. and one Ensign of the line as volunteers viz. Messrs. Creed, Kent, and Wrightson; also one Sergeant, and one private, all of the 27th Regiment; a detachment from the four companies of Rangers quartered on the island near Fort Edward; viz. Capt. Bulkley, Lieutenants Phillips, Moore, Campbell, Crafton [Crofton – ed.] and Pottinger; Ensigns Ross, Waite, McDonald, and White with 162 privates."

Initially Rogers' force headed down Lake George towards Carillon using the frozen surface of the lake to walk on. Then, after a council of war, a change of plans ensued. Rogers continues:

"On the morning of the 13th, a council of the officers determined that our better course was to proceed by land on snowshoes, lest the enemy should discover us on the lake. Accordingly we continued our march on the western shore, keeping on the back of the mountains which overlooked the French advanced guard, and halted at 12 o'clock two miles west of them, where we refreshed ourselves until three. This was to afford the day scout from the Fort, time to return home before we advanced, as our intention was to ambush some of the roads leading to the Fort that night, in order to trepan the enemy in the morning. Our detachment now advanced in two divisions, the one headed by Capt. Bulkley, and the other by myself. Ensigns White and Waite led the rear guard, the other officers being properly posted with their respective divisions. On our left, at a small distance, we were flanked by a rivulet, and by a steep mountain on the right. Our main body kept close under the mountain, that the advanced guard might better observe the brook, on the ice of which, they might travel, as the snow was now four feet deep, which made the travelling very bad even with snow shoes.

In this manner we proceeded a mile and a half, when our advance informed that the enemy were in sight; and soon after, that his force consisted of ninety six, chiefly Indians. We immediately threw down our knapsacks and prepared for battle, supposing that the whole of the enemy's force, were approaching our left, upon the ice of the rivulet. Ensign McDonald was ordered to take command of the advanced guard, which as we faced to the left, became a flanking party to our right. We marched within a few yards of the bank, which was higher than the ground we occupied; and observing the ground gradually descend from the rivulet, to the foot of the mountain, we extended our line along the bank, far enough to command the whole of the enemy at once. Waiting until their front was nearly opposite our left wing; I fired a gun as a signal for a general discharge. We gave them the first fire, which killed more than forty and put the remainder to flight, in which one half of my men pursued, and cut down several more of them with their hatchets and cutlasses. I now imagined they were totally defeated, and ordered Ensign McDonald to head the flying remains of them, that none of them should escape. He soon ascertained that the party we had routed, was only the advanced guard of 600 Canadians and Indians, who were now coming up to attack the Rangers. The latter now retreated to their own ground, which was gained at the expense of fifty men killed. There they were drawn up in good order, and fought with such intrepidity, keeping up a constant and well directed fire, as caused the French, though seven to one in number, to retreat a second time.

We however being in no condition to pursue, they rallied again, recovered their lost ground, and made a desperate attack upon our front, and wings; but they were so warmly received, that their flanking parties soon retreated to their main body with great loss. This threw the whole into confusion, and caused a third retreat. Our numbers were now too far reduced, to take advantage of their disorder, and rallying again, they attacked us a fourth time.

"Two hundred Indians were now discovered ascending the mountain on the right, to possess themselves of the rising ground, and fall upon our rear. Lieut. Phillips with 18 men was directed to gain possession of it before them, and drive the Indians back. He succeeded in gaining the summit, and repulsed them by a well-directed fire, in which every bullet killed its man. I now became alarmed lest the enemy should go round on our left, and take post on the other part of the hill; and sent Lieut. Crafton with 15 men to anticipate them. Soon after I sent two gentlemen who were volunteers, with a few men to support him, which they did with great bravery.

"The enemy pressed us so closely in front, that the parties were sometimes intermixed, and in general not more than 20 yards asunder. A constant fire continued for an hour and a half, from the commencement of the attack, during which time we lost eight officers and 100 privates killed upon the spot. After doing all that brave men could do, the Rangers were compelled to break, each man looking out for himself. I ran up the hill followed by 20 men, towards Phillips and Crafton, where we stopped and gave the Indians who were pursuing in great numbers, another fire which killed several, and wounded others. Lieut. Phillips was at this time, about capitulating for himself and his party, being surrounded by 300 Indians. We came so near, that he spoke to me, and said if the enemy would give good quarters, he thought best to surrender, otherwise he would fight while he had one man left to fire a gun.

"I now retreated, with the remainder of my party, in the best manner possible; several who were wounded and fatigued, were taken by the savages who pursued our retreat. We reached Lake George in the evening where we were joined by several wounded men, who were assisted, to the place where our sleighs had been left. From this place, an express was dispatched to Colonel Haviland, for assistance to bring in the wounded. We passed the night here without fire, or blankets, they having fallen into the enemy's hands with our knapsacks. The night was extremely cold, and the wounded men suffered much pain, but behaved in a manner consistent with their conduct in the action. In the morning, we proceeded up the Lake, and at Hoop Island six miles north of William Henry, met Capt. John Stark coming to our relief, bringing with him provisions, blankets, and sleighs. We encamped on the island, passed the night, with good fires, and on the evening of the next day (March 15) arrived at Fort Edward.

"The number of the enemy which attacked us, was 700, of which 600 were Indians. From the best accounts, we afterwards learned that we killed 150 of them, and wounded as many more, most of whom died. I will not pretend to say what would have been the result of this unfortunate expedition, had our numbers been 400 strong, as was contemplated; but it is due to those brave officers and men who accompanied me, most of whom are now no more, to declare that every man in his respective station, behaved with uncommon resolution and coolness; nor do I recollect an instance, during the action, in which the prudence or good conduct of one of them could be questioned."

Rogers, Robert, Reminiscences of the French War, Freedom, NH, 1988, pp. 47-53.

French Accounts

There are several French accounts of this incident. Here is one by the Chevalier de Lévis, second in command to Montcalm at this time:

"The day after the arrival of this detachment at Carillon, which was the . . .of the month of . . . , some Indians who had been hunting came to warn us that they had seen some tracks of an English detachment on Lac Saint-Sacrement. On this news, all the Indians and Canadians who were at Carillon to the number of two hundred fifty, left immediately under the command of the Sieurs de Langy and de la Durantaye and four cadets of the troops of the Marine. He also joined there some soldiers of the troupes de terre of good repute with the Sieur Forcet, lieutenant of La Sarre, and the Sieur Duresme, lieutenant of Languedoc.

"This detachment passed by La Chûte and marched toward the Montagne Pelée Now known as Bald Mountain in order to try to strike the enemy from that area. The Indian scouts, who formed the advance guard, met the enemy at an unexpected moment. They suffered their first fire. There were three Indians killed and the others withdrew with precipitation onto our detachment.

"The enemy, to the number of two hundred men chosen from the free companies under the command of Major Roger, initiated battle. Our detachment hastily advanced and the fight ensued; it was very lively on both sides; but finally our detachment entirely defeated that of the English, which was put to flight. Only eighteen persons escaped, including Major Roger. We had twelve Indians killed and eighteen wounded on our side. Our detachment spent the night on the battlefield. The following day, the prisoners and wounded were taken to Carillon. Six days after the affair, there came to Carillon two officers of Old England who had come to this course of action out of curiosity; they had not eaten in all this time and arrived dying of hunger."

Mitchell, James, ed. & trans., "For the Good of the Service:" the French and Indian War Journal of the Chevalier de Lévis, unpublished manuscript.

Here is yet another brief French account penned by Montcalm himself:

"Captain d'Hebecourt, of the regiment of La Reine, who commands at Carillon, having been informed, on the 13th of March, that the enemy had a detachment in the field which was estimated by the trail to number about 200 men sent a like detachment of our domiciled Indians, Iroquois and Nepissings, belonging to the Sault St. Louis and the Lake of the Two Mountains, who had arrived on the preceding evening, with some 30 Canadians and several cadets of the Colonial troops, under the command of Sieur de la Durantaye, of the same troops; Sieur de Langy, one of the officers of the colony, who understands petty war the best of any man, joined the party with some of the lieutenants of our battalion, who are detached at Carillon.

The English detachment consisted of 200 picked men, under the command of Major Rogers, their most famous partisan, and 12 officers. He has been utterly defeated; our Indians would not give any quarter; they have brought back 146 scalps; they retained only three prisoners to furnish live letters to their father. About four or five days after, two officers and five English surrendered themselves prisoners, because they were wandering in the woods, dying of hunger. I am fully persuaded that the small number who escaped the fury of the Indians, will perish of want, and have not returned to Fort Lydius.

Lydius was the French name for Fort Edward.

We have had two colonial cadets and one Canadian slightly wounded, but the Indians who are not accustomed to lose, have had eight killed and seventeen wounded, two of whom are in danger of dying."

O'Callaghan, E. B., ed., Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York, Vol. X, pp. 693, 697.

One thing is obvious from the various accounts; although they generally agree on the nature and outcome of the action, they differ significantly concerning the number of French engaged and the resulting casualties. This is where the historian's work begins to separate the kernels of truth from the differing accounts. Fortunately for us, possibly due to the fact that the exotic nature of the rangers caused them to be subjected to an inordinate amount of scrutiny, a wealth of literature concerning this skirmish in the winter woods is available to us.

The British commander-in-chief Lord Loudoun had planned a mid-winter blow directed against the French forts at Carillon [Ticonderoga] and Saint Frédéric [Crown Point]. Owing to a heavy fall of snow and a corresponding lack of snowshoes at Fort Edward, whence the blow was to be directed, this operation was canceled. On the 27th of February 1758 the cancellation was announced by the commander of the post, Lieutenant Colonel William Haviland of the 27th Regt. of Foot. Instead, on the following day, Haviland ordered a series of reconnaissance patrols to be directed northward towards Forts Carillon and Frédéric on Lake Champlain.

On the 28th of February a scouting party was sent out under Israel Putnam, who, as captain, commanded a ranging company of Connecticut provincials. Contrary to normal practice, while Putnam's group was out, Haviland made it known publicly that, when Putnam returned, Rogers was to be sent out with some 400 rangers.

On March 6 Putnam's party returned with one man, John Robens, missing in action, either having been captured or deserted. This gave Rogers no end of concern for fear that the missing man may betray his own planned departure to the French. Furthermore, on the same day a convoy of sleighs en route from Fort Edward to Albany on the Hudson river, which was frozen over this time of year, was ambushed by a group of French and Indians north of old Saratoga. The servant of Edward Best, who was one of the rangers' sutlers, was taken captive. It was feared that he also may inform the French of Rogers' plans.

In the event, although Rogers had misgivings, there is no evidence that either man reported his planned mission to the enemy. However Rogers did not know this; indeed he had more reason for anxiety, for, when he finally received his marching orders on the 10th of March, he found out that, instead of the promised 400 men, he was only to have 180 men and officers to dispose of.

Despite his misgivings, Rogers and his rangers, 184 men in all, having been augmented by several volunteers, left their camp on the island at Fort Edward on the mid-afternoon on March 10 and marched to the half-way brook, on the road leading to Lake George, camping there for the night.

On the 11th, the rangers reached Lake George, where they passed by the burned-out ruins of Fort William Henry. Then, continuing onto the frozen surface of the lake, they advanced to the Narrows where they camped on the east side of the lake.

On the 12th, the march resumed at sunrise. The rangers, with ice creepers clamped to their feet so as to facilitate their movement over the slippery frozen lake surface, proceeded in extended order up the lake. About three miles up the lake, a dog was seen scampering across the ice. The party halted while Rogers sent out scouts to investigate. Dogs frequently accompanied Indian raiding parties. The scouts returned with nothing to report. However a cautious Rogers ordered his men to remove their ice creepers, had them put on snowshoes, and directed them into the woods. They moved through the woods, skirting the east shore of the lake, and headed north as far as Sabbath Day Point on the opposite side, arriving there by ten o'clock in the morning. Here Rogers rested his men for the remainder of the daylight hours.

With the coming of night, the march northward on the lake continued. Lieutenant Phillips took the lead, and a volunteer from the Royal Highland "Black Watch" Regiment, Ensign Andrew Ross, led a flank guard along the west shore of the lake.

Eight miles from the French advanced post at Bald Mountain Lieutenant Phillips reported that he had spotted a fire on the east side of the lake. The rangers advanced cautiously in hopes of bagging some prisoners, but the fire was never located with Rogers concluding that Phillips had mistaken a phosphorescent patch of rotting wood for a fire. The rangers crossed the lake and took up a defensive position on the west shore, where they rested for the remainder of the night.

13 March 1758, dawned with a meeting of the officers. It was unanimously agreed that the patrol should march inland to the west and circle around Bald Mountain so as to avoid being spotted by the French post there. Leaving rangers Cunningham and Scott with their cached sleighs to warn of any enemy who may be following, the rest moved forth on snowshoes at seven a.m. following the Route des Agniers or Mohawk Trail. At eleven a.m. they stopped to eat a cold meal behind a ridge opposite the French outpost and waited for the daily French relief and resupply party to return to Fort Carillon. At three p.m. the rangers resumed their march down the valley of Trout Brook intending to lay an ambush. As he marched toward his appointment with destiny, Rogers did not know, nor did any of his men, that his force had already been discovered.

Many hours earlier a scout of six Abenaki Indians had been making their way across the ice, returning from the vicinity of Ft. Edward, when they noticed something peculiar on the frozen surface of Lac St. Sacrement. The ice creepers that the rangers wore left recognizable patterns in the ice. By following these patterns, the Abenakis were not only able to find the site where the rangers had camped the previous night, but they were also able to estimate the size of their party at close to two hundred. Returning to the ice, the Abenakis headed north as quickly as they could to alert the garrison of Ft. Carillon.

Around one p.m. the party of Indians arrived outside the French fort and alerted the Crees, Nipissings, and Caughnawagas in the nearby village below the fort of the English menace. As soon as he was alerted the Sieur La Durantaye, commander of the Compagnies Franche de la Marine, who had arrived the previous evening with thirty French marines and 200 Iroquois, assembled some 95 men, mostly Indians, with whom he marched forth to counter the enemy threat. He was followed fifteen minutes later by a larger force of some 205 soldiers including a number of Compagnie Franche de la Marine troops as well as Canadian militia, Indians, and some regulars of the Troupe de Terre regiment la Reine. This latter force was commanded by the partisan leader Jean-Baptiste Levreault de Langis de Montegron, often referred to as "Langis" or "Langy." Both forces had left the fort by one-thirty p.m.

The rangers were organized in two divisions, with an advanced guard of around eleven men under Ensign Gregory McDonald and a rear guard under Ensigns Joseph White and James Waite. The remaining rangers were distributed, probably equally, between the lead division under Captain Charles Bulkeley, and the division commanded by Rogers himself, which followed closely behind.

More Battle of Snowshoes 1758

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. XI No. 1 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by James J. Mitchell

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com