Editor's background information on the camp of Bunzelwitz: The poor condition of the Prussian army in 1761 dictated a change in tactics for Frederick. He anticipated the most of the action during the coming campaign would be in Silesia, so he transfered the best regiments to his army and saddled Prince Henry's army with large numbers of frei korp and new recruiters of lesser quality than the traditional Brandenburg-Pomeranian stock. Frederick was also vastly outnumbered in 1761. The Austrians eventually brought a force of 72,000 troops together in Silesia under the command of Loudon. To these were added 47,000 Russian regulars commanded by Buturtin and numerous Croats and Cossacks, bringing the Allied total up to 130,000 men in Silesia. Against this force, Frederick could scrape together an army of 55,000 men of mixed quality.

Frederick adopted the sensible strategy of anchoring his army on the fortress-depot of Schweidnitz and digging himself into an armed camp where he would wait for the Allies to make the next move. Frederick would demonstrate his capacity for operating on the defensive, for a change. The 'Camp of Bunzelwitz' was located in the gently rolling terrain west of Schweidnitz. Work on the camp commenced on August 20, 1761 and was considered defensible within three days. The perimeter was 15,000 paces and was oblong in shape Duffy provides a discription in his book, The Army of Frederick the Great thusly:

- In this location the Prussian army stood on a series of low and

mostly gentle eminences, which were utilised in a masterlyfashion.

The approaches were by no means physically insurmoun table, but

what rendered them difficult were the little streams, the swampy

meadows, and the enfilading and grazing fire from the batteries oil

every side. You could see fortifications with ditches 16 feet deep and

as many wide ... in front of the lines the Prussians had hammered in

palisades, and planted stonn. poles and chevaux de frise, and in front

of these again had been dug a triple row of 6-feet deep pits. The batteries seemed to be everywhere, each provided with two fougasses, or holes filled with gunpowder, shot and shells, which had been dug outside and were ready to be touched off at any moment by men with

powder trains running through the tubes.

Frederick remained in his armed camp from August 20th to September 26th. Loudon devised a coordinated plan of attack scheduled for September Is(, but the Russian generals convinced Buturlin to withdraw his approval of the plan. Buturlin did more than that for he pulled out two-thirds of his Russian troops on September 9th and crossed over the Oder to look for provisions. By September 26th, Frederick deemed the threat to have passed and he abandoned the armed camp, marching to Neisse, which was well- stocked with provisions.

Loudon, however, had more mischief in mind and on September 30th, organized and carried out the stunning escalade of the fortress of Schweidnitz, which fell without a formal siege. The loss of Schweidnitz was a devastating blow to Prussia, depriving the army of a reliable supply depot and enabled the Austrians to spend the winter on the Prussian side of the mountains for the first time during the war. It had a considerable negative effect on Prussian morale. By year end, Daun had practically maneuvered Henry out of Saxony and Colberg fell to the Russians.

Returning now to Fritz Mueller's commentary:

Traveling west from Breslau we arrived at the small village of Wurben. About a mile's march brings us up steep slopes to the high ground of the Prussians' 1761 fortified camp, just east of the village of Bunzelwitz. From this commanding berg we can observe Bunzelwitz (Boleslawice), Tunkendorf, Alt-Jauernick, Neudorf and Wurben. The surrounding countryside is interspersed with forests and marshes which limited any approaches to attack the camp to a very few. Frederick chose this ground wisely.

The hill is still covered with entrenchments and huge holes in the ground that probably served as underground supply and munitions dumps for the garrison. Any actual fortifications or other structures have long since vanished. Our map showing the redoubts and other fortifications constructed by the Prussians testifies to the strategic planning that went into the camp layout. It is not surprising that the Austrians and Russians were reluctant to attack head-on as Frederick hoped they would. It is amazing to think that the camp was constructed in three days.

After a walk-around and many pictures we trek back down the hill, board the coach and travel to the western side of the camp via Schweidnitz, Alt Jauernick and Zedlitz. Our path parallels the Prussian lines facing the west, and the Russian camp of Stanowitz and in front of Striegau. Loudon must have been extremely frustrated at having his arch rival penned up, virtually surrounded, and not able to get at him without risking a humiliating defeat or terrible casualties. Finally, they learned how the Prussians felt in most of their battles against the Austrians - having their enemy hunkered down behind works like a bunch of cowards.

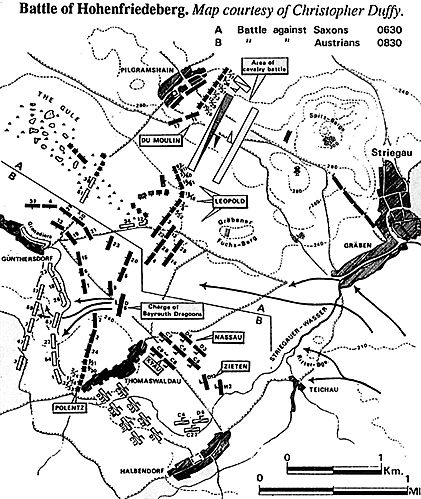

On to Hohenftiedeberg (Dobromierz). We head west only a short distance to reach the site of this 1745 battle. This is one of my favorite battles, and next to Leuthen, one of the best sites we visited on the (our, in my opinion. The battlefield is much the same as it must have been in 1745. The villages have grown, certainly, but this out-of-the-way locale seems to have been left in the I 8th Century.

We first visit Pilgramshain, where the initial actions were fought against the Saxons; where the Prussians mauled the Saxons. The fields between the village and the Spitz Berge are still cultivated fields and still suggest good ground for cavalry action. Then, passing through the Gule, we move through Guntersdorf, where the second phase of the battle occured and where the Prussians smashed the Austrian grenadiers and Austrian left flank. We pass field upon which the historic charge of the Bayreuth Dragoons took place which smashed the Austrian center. Then we go into Thomaswaldau, on the Austrian right where Zeiten's timely cavalry charge saved the Prussian left wing.

The battle is memorable not only because of the Bayreuth Dragoons, but also because it was the first action in which the oblique order of attack was used by the Prussians. In reading the various accounts of the evolution of the action I find myself wondering if the oblique deployment wasn't as much a matter of circumstance as it was/may have been a matter of design and planning. No matter, the tactic was effective and decisive. C'est la guerre!

Editor's comments on Hohenfriedeberg:

I won't add any details of the battle to Fritz's account since it is well covered in Volume VI Issue No. 2 of the Seven Years War Association Journal, but I will add several comments about the battlefield terrain. On the north end of the battlefield, most of the fighting took place between Striegau (to the cast.) and Pilgramshain (to the west).

In between these two villages lies the sizeable Spitz-Berge and the un-named windmill hill. The Spitz-Berge is being excavated by a gravel company and a large chunk of it has already disappeared. I would imagine that. this terrain feature will not even exist in a few more years. The area around Pilgramshain was hillier than I would have imagined, based on the topographical maps that I have seen - sort of a rolling hills and dales that would not seem inducive to the fierce cavalry action that took place between the Prussians and Saxons.

The Gule appears to have been drained and converted into lush farmland. The whole area was awash with colorful bright yellow rape seed. I don't believe that rape seed was a crop until the 19th or 20th Century. Much of The Gule has been divided by tree lines that provide a wind break, so from the modern day perspective, the area does not look like it might have in 1745.

At the south end of the battlefield, the area between Gunthersdorf (west) and Thomaswaldau (east) is as flat as a pancake and the perfect spot for a well-drilled army like Frederick's to fight a battle. My final impression of Hohenfriedeberg is that it was one of the largest, in area, battlefields that I have ever seen. I imagine that it would have been very difficult for Frederick to know what was going on from one end to the other. If you walk through the streets of Thomaswaldau, keep a sharp eye open for some grape shot and round cannon shot that some of the farmers have placed atop iron pipes as decorative finials. This is the only evidence that a great battle took place in this bucolic little town in Silesia.

More 1998 Frederick the Great Tour

-

Frederick the Great Tour: Introduction

Frederick the Great Tour: May 16: Kunersdorf

Frederick the Great Tour: May 17: Leuthen

Frederick the Great Tour: May 18: Landeshut and Mollwitz

Frederick the Great Tour: May 19: Bunzelwitz and Hohenfriedberg

Frederick the Great Tour: May 20: Liegnitz

Frederick the Great Tour: May 21: Glatz (Klodzo)

Frederick the Great Tour: May 22: Burkersdorf and Reichenbach

Frederick the Great Tour: May 23: Zorndorf

Frederick the Great Tour: May 23: Last Night in Berlin

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. X No. 3 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by James E. Purky

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com