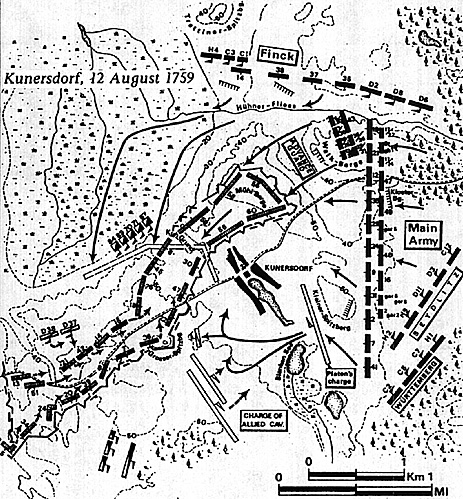

The next morning we loaded onto our coach for the first leg of our journey to Kunersdorf (Kunowice). This 1759 rematch between the Prussians and Russians (and Austrians) was one of Frederick's worst defeats and could well have ended the SYW three years early. I will not go into the histories of the battles that visited, as most of you know them as well as I, so fill in the blanks where appropriate.

Our coach stopped in Kunersdorf (Kunowice) near the Kleiner-Spitzberg. We walked through the village to the south and located the ponds upon which Frederick anchored his left flank. Moving on to the west edge of the village, we looked over the rolling fields where the cavalry action between Loudon's Austrian/Russian horse and Platen's Prussians occurred. It is easy to see how the Allied cavalry hid itself in the folds. of the ground and were able to spoil Platen's cavalry attack toward the Allied center on the Grosser-Spitzberg.

Back through the village to the north, we marched around the Muhl-Berge where the Prussian infantry made their flank attack into the Russian positions. This hill (berge) is now covered with trees, but certainly posed a formidable obstacle for any attacker. No one can be certain how the Prussians were able to storm this hill. Some say that the heat of the day caused the Russian defenders to malinger in their trenches, but the Prussians had to be hot and thirsty too. Of course, Prussian discipline was obviously a factor that helped carry the attack through, not to mention the soldiers' natural fear and a few well-placed spontoons.

But I personally think that the Russians were flabbergasted that any soldiers, even Prussians, would be audacious enough to storm up a 60-foot hill topped with redoubts and other earth works, in the face of point-blank musket fire, and attack them. In their bewildered state they stood like deer caught in headlights and in those moments of shock and disbelief, fell victim to the Prussian bayonets. All that could be seen of the Russian survivors were elbows and boot soles as they retreated down the southwest slope of the Muhl-Berge, through the Kuh Grund (literally, "cow path") and up the slope on the far side seeking refuge. It was this path that we followed to the western edge of the Muhl-Berge.

From the top of the Muhl-Berge on the western edge we could see the town of Frankfurt- an- Oder on the German side of the Oder River, and the Trettiner-Spitzberg, the point where Frederick held his initial reconnaissance of the Allied positions. As we passed over the Muhl-Berge we found what appeared to be entrenchments which may have been part of the Allied works facing the northwest.

[Editor: Professor Duffy also noted that the earthworks might have been the remains of German artillery positions dug in 1945.]

They were very overgrown but had not been filled in. A couple of us wished for metal detectors and a few hours time to search the grounds. [Editor: We met a German couple, here, who had hiked from Frankfurt to Kunersdorf to explore the field. We could tell that they were history buffs because they had a copy of the German General Staff map for Kunersdorf. They gave us directions to the Kuh Grund and pointed out the location of a monument on the site where Frederick was lightly wounded. Time and distance kept us from looking for the monument.]

Moving down the west side of the Allied line, we came to the Kuh Grund, where the Prussian attack stalled. This area on the the west is dominated by abandoned concrete structures that represent the remains of a Polish military base. A road leads us into the Kuh Grund, which is a narrow valley between the Muhl-Berge ( on our left ) and a ridge line continuing southwest ( on our right ).

The valley varies in width from 100 feet to 200 feet and angles between the hills on either side. Recent excavations distort the heights of the hill the Russians held in the second assault, but the rise is at least 15-20 feet in its shallower portions and is almost perpendicular. I stand amazed and in awe at the courage these Prussians must have had to assault this natural wall. By the histories, Frederick's generals continued to feed men into this gap without a clear understanding of what they faced, or what. the butcher's bill would tally. It is eerie to stand on the same ground where so many died in a futile attempt to win a victory. The name Kuh Grund could easily translate into "meat grinder". Indeed, that is what this cow path was to those who fought here.

The Kunersdorf battlefield is immense and impossible to take in at any one point. The ground surrounding the area is forested and marshy and the soil is very sandy. There appears to be very little room for an 18th Century army to maneuver effectively, and impossible for any general, even Frederick, to manage without a helicopter. The Allies chose their position well. Frederick showed poor judgement in attacking, in my estimation, but he could not leave so large a force so close to Berlin without forcing a battle.

Back to the coach and on to Breslau (Wroclaw). We reached our 4 star hotel (self-proclaimed it would seem), the Hotel Wroclaw, checked in and grabbed a quick dinner. The coffee is great at dinner, and everything else is adequate.

Editor's additional comments:

We left Kunersdorf at 4 P.M. and arrived at Breslau around 7 P.M. Our route was via Crossen on the Oder and Lubin. On the outskirts of Breslau, we passed over the field of Leuthen, following the approach march of Frederick's army. Christopher Duffy pointed out the famous Leuthen churchyard and I resolved to take tons of pictures so that Herb Gundt could make a model for me. The battlefield site is only a few short miles from the outskirts of Breslau. The Hotel Wroclaw is a modernistic, though tired looking high rise that lacks any kind of charm. However, the rooms were clean, the beds were comfortable and you could get CNN on the cable television. That night, I watched some Monty Python reruns, dubbed in Polish, but none the less, still quite funny.

All in all, the hotel was better than expected and is a decent place to stay if you happen to be visiting the Silesian battlefiels. The hotel seems to attract older tourgroups of Germans. The hotel food was rather dodgy. Every meal was served with fried potatoes. After several nights of this, several tour members decided to forgo the hotel fare and they ventured into town for their dinners. I am told that the restaurant fare was quite tasty and I regret that I didn't join the masses that ate in the town. By the end of the week, only 6-8 of the members chose to eat at the hotel.

Breakfast consisted of eggs, sausages, bacon, cereal, yoghurt, cold meat, cheese and biscuits. Packed lunches were about 30 DM and were a bit of a rip-off in terms of the value received for the money. Eventually, everyone walked across the road to the BP gasoline station and purchased meat, cheese, bread and fruit in order to make their own picnic lunches. Average cost was about 2-3 DM (German marks). This way, one could make a better sandwich than the one provided by the hotel at a fraction of the cost. This is generally the way to go whilst traveling in Europe. The BP station became out primary food commissary throughout the trip. This, along with lots of chocolate candy bars, explains why I gained ten pounds on the trip.

Breslau (or Wroclaw) is worth the visit on its own merits. The central town square has been restored to its original condition and one can get a flavor for how Frederician Breslau might have looked. Breslau was virtually flattened by the Russians during the latter days of World War II, in part, because of the tenacious German defence of the city, which had been turned into an armed fortress, i.e. Festung Breslau. The town also has a major university with about 30,000 students, and is the home of the panorama painting of the Battle of Raclowice (fought in 1794 between the Poles and the Russians). The Poles, commanded by Thaddeus Koscuiskl, defeated the Russians, so you can imagine how important this event is to the Poles in terms of nationalism. The panorama is well worth the visit.

During most of the evenings, tour members would high tail it to the town plaza in the center of the city where we would sit in one of the numerous outdoor cafes that line the plaza. There we would swap stories and jokes (the Brits on the tour won the joke-telling contests, hands down. We Americans couldn't compete with the likes of Phil Mackie, Mike Kirby and tour co-ordinator Steve Howe. I remember laughing so hard one time that I was nearly in tears.). When we weren't laughing it up, we were enjoying the local ales and people watching.

More 1998 Frederick the Great Tour

-

Frederick the Great Tour: Introduction

Frederick the Great Tour: May 16: Kunersdorf

Frederick the Great Tour: May 17: Leuthen

Frederick the Great Tour: May 18: Landeshut and Mollwitz

Frederick the Great Tour: May 19: Bunzelwitz and Hohenfriedberg

Frederick the Great Tour: May 20: Liegnitz

Frederick the Great Tour: May 21: Glatz (Klodzo)

Frederick the Great Tour: May 22: Burkersdorf and Reichenbach

Frederick the Great Tour: May 23: Zorndorf

Frederick the Great Tour: May 23: Last Night in Berlin

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. X No. 3 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by James E. Purky

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com