The Cannon’s Breath

Jean-Baptiste Vaquette de Gribeauval

and the Development of the French

Artillery Arm:

1763-1789

by Kevin Kiley, USA

| |

Introduction [1]

‘General de bataille, commandant

en chef du genie, de l’artillerie et des

mineurs’ ‘’[The artillery officer] is devoted

to perfecting his art in order to make

himself better able to render the most

notable services during war, which make

him known for good reason as the most

solid support of the state'. -Lombard

‘no subordinate, no matter what

seniority he possesses, may be promoted

without a demonstration of intelligence

and his capacity to perform the functions

required by the artillery.’ - Valliere pere

‘Leave the artillerymen alone. They

are an obstinate lot.’ ‘Cannon his name, Cannon his voice, he came.’ Down the long, rutted road of the

history of warfare stride the gunners,

some famous, some not so

famous, who have fought their guns beside the

captains they served. Most of these children of

St. Barbara were masters of their art. Others,

were innovators and developers of systems.

Their names are associated with a string of

hard-fought victories, desperate stands, and

the smoke and rumble of the guns they served.

Gustavus Adolphus, Lennart Tortensen, the

great Turenne, Phillips, Frederick the Great,

Prince Lichtenstein fought their guns, swore at

them stuck in mud-encrusted country roads,

and fought desperately in their defense.

The greatest gunner of them all, Napoleon, general

and Emperor, commanded ‘as expert a lot of

artillerists as ever rode together under the

same banner’: Drouot, Senarmont, Eble, Marmont,

Foy, and Lauriston. The artillerymen of

many nations who faced him were equally as

skilled: Smola, Dickson, Frazer, Kutusaiv and

others who belonged to the ‘traditional brotherhood

of Stone Hurlers, Archers, catapulteers,

Racketeers, and Gunners’.

One of the greatest artillerymen in history,

whose innovative approach to artillery

development has had the system he developed

hailed as ‘perhaps the most important innovation

in the history of artillery’ [3] ,

pioneered an artillery system that ushered in an era and

eventually enabled the artillery arm to become

a decisive combat arm on the battlefield.

That gunner’s name is Jean-Baptiste Vaquette de

Frechencourt de Gribeauval, and the artillery

system that bears his name was a key development

in both tactics and technology that

greatly helped enable the armies of the French

Republic and Empire to advance against the

armies of the kings in sweeping campaigns

that ‘put fear into the souls of Europe’s kings

and foreign generations’. [4]

Jean-Baptiste Vaquette de Frechenmont

de Gribeauval, French artilleryman and innovator,

and inventor of the artillery system that

bears his name, was born in 1715 at Amiens

of a family that had contributed both military

men and magistrates to the nation and had

been ennobled for service to the state.

As a strange omen to what he would later become,

he was baptised on 4 December, the feast day

of Saint Barbara, the patron of artillery. His

father was a lawyer and the Mayor of Amiens.

Gribeauval entered the army as a volunteer

in 1732, entered the artillery school at La

Fere as a cadet in 1733, and was commissioned

as an ‘officer pointeur’ [5]

upon successful

completion of the course in 1735.

One of his instructors at La Fere was the famous

Bernard Forest de Belidor, who had figured

out that the powder charge for artillery pieces

could be reduced to half what it had been and

not affect the range of the piece.

By 1743 Gribeauval was appointed a ‘commissaire extraordinaire’

in the artillery, and four years later a ‘commissaire ordinaire.’ [6]

Gribeauval quickly attained a reputation in the French

service for technical ability and ordnance construction.

In 1748, after combat service during

the War of the Austrian Succession in both

Flanders and Germany, he designed a fortress

gun carriage that was later copied throughout

Europe. He also recognised, as did other

French artillerymen and senior officers that

the Valliere System of artillery was too large

and heavy for use as field artillery and was

completely unsuitable for a war of manoeuvre.

In 1752 he was promoted to captain of miners. That same year he undertook an inspection

trip to Prussia to study their light

artillery that had given the Austrians so much

trouble in the late war. It should be noted that

at this period, the French engineer arm was

part of the artillery. While miners were specialists

in the underground war of mine and

countermine during sieges, they were normally

commanded by artillerymen, and this

was a usual assignment for artillery officers. [7]

The French engineers didn’t become a separate

branch of the service until 1758 and the

new Royal Corps of Engineers was small and

composed entirely of officers, none higher

than the rank of colonel. [8] Artillery officers

were also taught siege tactics and the engineering

processes that went along with those

operations in the excellent French artillery schools.

In many ways, French artillerymen of

this period were just as familiar with engineer

and infantry tactics as the officers of those two branches.

The outstanding Prussian artilleryman,

Lieutenant Colonel Ernst Friedrich von Holtzman,

had developed a light, very mobile field

artillery which Gribeauval was able to observe

first-hand. [9] He obtained plans for some of the

Prussian pieces and had one constructed and

test-fired when he returned to France. In 1757

he was again promoted, this time to lieutenant

colonel of infantry, and that same year he and

other French artillery officers were seconded

to the Austrian army for service with their

artillery and engineers, based on a request by

the Austrian Empress Maria-Theresa because

of a shortage of qualified artillery officers in

Austria.

Gribeauval’s service in the Seven Years’

War was distinguished. He served at the Battle

of d’Hastenbeck and at the capture of Minden.

Service at the siege of Neiss resulted in his

being created ‘general de bataille et le donna

commandant de l’artillerie, du genie, et des

mineurs’ by Maria-Theresa with the consent

and approval of his sovereign, Louis XV. He

directed the siege of Glatz, under the overall

command of Field Marshal Loudon, finally

taking the city by a daring, well planned, coup

de main. He defended Schweidnitz against the

Prussians, as commander of the artillery and

engineers, with Frederick the Great being

present, inflicted 7,000 casualties for 1,000

incurred and was ordered to surrender only

after having run out of ammunition.

Frederick was so impressed with the performance that he

tried to entice Gribeauval into his service. The

Austrian miners, which had been reorganised

and trained by Gribeauval, completely out-classed

their Prussian counterparts, one Prussian

engineer officer remarking that ‘it is only

in the French service that you can carry out

such operations with real proficiency, for in

that army the technical officer is treated with

respect and is given everything he needs. It is

not the individual who carries the burden, but

the corps as a whole.’ [10]

For his efforts, Gribeauval was promoted

first to oberstleutnant in 1759 and then to

General-Feldwachtmeister in the Austrian

service (the equivalent of French lieutenant

general) and was awarded the Grand Cross of

the Order of Maria-Theresa by a grateful Empress.

Recalled to France, he was promoted to

Marechal de Camp on 25 July 1762 and was

awarded the Order of St. Louis, grade of Commander, in 1764.

Promoted to Lieutenant General on 19 July 1765, he was later awarded

the Grand Cross of the Order of St. Louis in

1776. He was made First Inspector General

of Artillery on 1 January 1777.

While in Austria, Gribeauval was considered

by his Austrian counterparts as a

‘collaborateur’ of Prince Lichtenstein and

that he had contributed to the improvement of

the Austrian artillery while in their service. [11]

The French artillery was an ancient

and honourable arm with a well-established

organisation and tradition when Gribeauval

proposed its complete reorganisation in 1762.

The first French artillery school was unofficially

organised at Douai in 1679, becoming

‘official’ in 1720. The artillery and engineer

schools of the other powers patterned themselves

on the French artillery and engineer

school system, some sooner than others. ‘The

artillery schools of ancien regime France were

the first institutions in Europe where students

received a scientific education”. [12]

The Fusiliers du Roi was officially

formed in 1672, and while not properly artillerymen

and organised as infantry, provided

the muscle to man artillery batteries in the

field, and defended their guns alongside the

gunners in close combat. In 1693 they became

the Regiment Royal Artillery and by 1710 the

regiment was made up of five battalions (236

officers and 3,700 other ranks). By 1684 the

Regiment of Bombardiers du Roi was formed

consisting of two battalions by 1710 (90 officers

and 1,450 other ranks). They were specialists

who manned mortars and were separate from Royal Artillery. [13]

From 1679, the French operated

with two systems of artillery, that of de veille

invention, which were the ‘traditional’ pieces

with which France had usually equipped her

artillery, and de nouvelle invention which was

introduced into French usage by the Spaniard

Antonio Gonzales.

Introduced into French service in that year the guns of de nouvelle

invention gave the French army an artillery

system that was light, mobile, and a precursor

to what Gribeauval would eventually achieve.

Gonzales’ tests at Douai in 1680 were noticed

by the artilleryman, Lieutenant General Francois

de la Frezeliere, who was enthusiastic

about the light system, and employed them on

campaign with the field armies.

Gonzales’ light artillery system suffered

from three drawbacks. First, the gun tubes had

a chamber at the end of the bore that was of

greater diameter than the bore itself. This led

to problems with leftover powder residue,

which might prematurely detonate the next

rammed charge. Second, the lightness of the

pieces caused very violent recoil, which was

retarded with heavier pieces, and this damaged

gun carriages and adversely affected

recoil. Third, the vent of the piece was not at

the top, vice the rear, of the breech, which may

have been a cause of the very violent recoil of

the piece as the powder now burned differently.

The system fell into disuse after Frezeliere’s death and was formally abolished

in 1720. Still, it was a harbinger of things to come. [14]

The Valliere system of artillery

emphasised range and accuracy and there was

no distinction made between siege, garrison,

and field artillery. Also, there was no attempt

by Valliere to standardise gun carriage and

vehicle construction, and there was no central

construction tables for artillery vehicles.

Therefore, gun carriages constructed in one

part of France were not compatible with those

built elsewhere. This was actually done on

purpose by Valliere, as the guns cast in different

foundries might be of different weight

from those of the same calibre cast in another.

Gun carriages were specifically built to accommodate

a certain gun tube. This led to

much duplication of effort and there was no

standardisation of parts.

The Cannon’s Breath Jean-Baptiste Vaquette de Gribeauval and the Development of the French Artillery Arm: 1763-1789

|

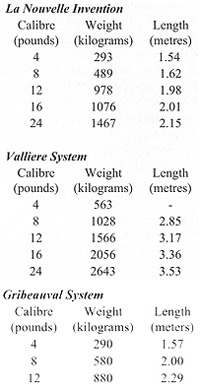

The table is a comparison

of the weight and length of the gun tubes of

the systeme la nouvelle invention, the Valliere

System, and the Gribeauval System:

In 1732 General Jean Florent deValliere

(1667-1759) brought order out of chaos in the

French artillery by limiting the calibre’s used

and standardising the casting and manufacture of gun tubes.

The table is a comparison

of the weight and length of the gun tubes of

the systeme la nouvelle invention, the Valliere

System, and the Gribeauval System:

In 1732 General Jean Florent deValliere

(1667-1759) brought order out of chaos in the

French artillery by limiting the calibre’s used

and standardising the casting and manufacture of gun tubes.