Eclaireurs de la Garde Imperial

Organization

by Paul L. Dawson

| |

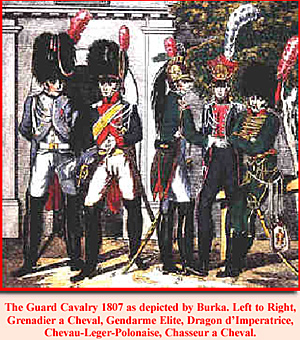

The Guard Cavalry 1807 as depicted by Burka. Left to Right,

Grenadier a Cheval, Gendarme Elite, Dragon d’Imperatrice,

Chevau-Leger-Polonaise, Chasseur a Cheval.

As with the infantry of

the young guard, the Russian

campaign had decimated

most of the army. In

the new year of 1813 Napoleon

began reconstructing

the cavalry of the Guard.

This was achieved primarily

by converting existing

velite organisations into

Young Guard formations.

The Velite squadrons

created for the cavalry of the

guard in 1806, became essential

elements of the

Guard. They were formed

from physically fit men who

aspired to be the officers of

the future, and were willing

to pay 300 francs a year for

this privilege. If the payments

stopped, in the absence

of extenuating

circumstances, the velite

would be sent to the line.

The establishment of the Velites a Cheval in 1806 was as follows:

Chasseurs a Cheval (5 and 6 squadron)

Dragons d’Imperatrice

The velite squadrons were considered to be the ‘nurseries’ for officers of the line, and after

three years service, each velite would be tested to determine whether he was qualified for junior

officer rank in the line or whether he should be retained within the guard, without full

qualifications for membership. The decree of 15 April 1806 stated that when on campaign,

the velite squadrons were distributed amongst the old guard companies to make them up to

250 men, and that any surplus would be used to form a fifth squadron.

The regimental organisation of the parent unit consisted of:

Each squadron contained:

The guard cavalry had two primary roles; they served as a body guard for the Emperor;

and constituted a formidable battlefield reserve striking force under the direct command

of the Emperor, which was employed at the critical point in a battle. In addition to this, the

light cavalry regiments became and eyes and ears of the guard when employed as scouts or

screening and advanced post duties.

The first role was set out meticulously in advance by a series of decrees and orders. The

four colonel-generaux of the guard took in turn, on a weekly basis, the duty of being

constantly in attendance of the Emperor. In the palace they occupied rooms near his, and

in the field they slept in his tent. At all times whether in Paris or the field, each of the guard

cavalry regiments furnished a duty squadron for the Emperors headquarters. When in Paris,

the duty squadron was rotated every three weeks. When the Emperor left his headquarters

on horseback, the four duty squadrons rode, some 1000m behind him.

It is the second role of the guard cavalry, that was perhaps most important.

In the spring of 1813, the reconstruction of the army began. Napoleon decreed that

each guard cavalry regiment was to be expanded to become a brigade, consisting of one

young guard and one old guard regiment. Thus the chasseur brigade consisted of 10

squadrons of 250 men each. The first five squadrons of each regiment were designated

as old guard and known as premier chasseurs/grenadiers/dragoons/lanciers, the

last 5 squadrons were young guard and known as second chasseurs / grenadiers / dragoons / lanciers.

On 17th March 1813, acting on the decrees of 18 and 23 January, 23rd February

and 6th March, Napoleon attached young guard squadrons to the Grenadiers a Cheval,

Dragoons and chasseurs a cheval: the officers below the rank of Capitiane, NCO’s and other

ranks were classed as Ligne, but were to wear the same distinctions as their guard counter

parts. The decree of 23 January had created the grenadiers and dragoons ‘en second’, and

that of 6 March a 9th chasseur cheval squadron.

This new call for men allowed the Dragoon regiment to be recruited up to strength,

plus the formation of the 2nd Dragoons, Lieutentant-General de Brigade Testot-Ferry was

chef d’escadron of these cavaliers-seconds. Pinteville commanded the young guard regiment.

The Grenadiers four original squadrons were also replenished, and were commanded

by General Walther.

As well as increasing the existing guard cavalry regiments, Napoleon still had desperate

need for cavalry. What he needed were educated men of private means, who were

accustomed to riding, who could not only learn their new trade quickly but could also

provide their own uniforms and horses. With his cavalry arm frozen to death in Russia,

Napoleon decided that the situation obliged him to call upon the son’s the of the leading

classes from all over the Empire; these men were placed in the regiments of ‘Gardes

d’honneur’. This was both a political and military necessity.

Another problem faced Napoleon, the lack of a cadre for the new young

guard regiments or any new cavalry formation. Most of the surviving

NCO’s were now promoted to officer rank, or were needed in the field,

had damaging consequences on the training of the new recruits for the

guard.

In August 1813 the organisation of the Guard cavalry, then 8000

strong, and under the command of General Nansouty was as follows:

2eme Division: General Lefebvre-Desnouettes.

3eme Division: General Walther

By 1814, not only were experienced cavalry generals in short

supply, but arms, horses and equipment. The responsibility of re-equipping

the survivors and of providing for the conscripts fell mainly on

General Preval. Preval commanded the cavalry depot at Versaille,

where units arrived deficient in everything but breeches and waistcoats,

and where there was only 6,284 horses of the 9,786 needed.

‘The men must have boots and horses’ Preval pointed out to the

Minister of War, but despite these difficulties, Preval succeeded in

mounting, equipping, clothing and arming 12 regiments of cavalry in

one month.

Operations in Saxony during 1813 had made Napoleon realise that

it was imperative that he found a means of dealing with the constant

harassment of his troops by Cossacks. After considering various solutions

to the problem, the decree of 9th December 1813 set out the

organisation of the guard for the campaign of 1814.

This decree created the scout regiments, each of four squadrons of 250 men, and were

attached to the Grenadiers, Dragoons and Polish Lancers. The scouts had been first muted in

1806. The decree of 9 July 1806 set out the authorisation for a project to form 4 regiments

of scouts, consisting of 4 escadrons of 200 men. Napoleon recommended that the horses

were to be no more than 14 hands due to the difficulty in obtaining larger horses.

The uniform was to be a shako, habit, waistcoat,

breaches, overalls, stable jackets, overcoat and

hussar boots. They had no schabraque and

were to be armed with a carbine and light

cavalry sabre. The men were to be less than 5

feet tall, i.e. all men who were too short to join

the Dragoons. Napoleon thought that the

scouts would act as the cavalry version of the

infantry Voltigeurs and carry out the duties of

the chasseurs a cheval and hussards, i.e.

screen in advance of the army.

The French seem to have had a perpetual lack of cavalry

and by keeping the light cavalry with the bulk of the cavalry, Napoleon could disperse the

scouts ahead of the army and not reduce his cavalry corps of fighting men.

The project seems to have been abandoned, until 1813,

when the decree was implemented. Although only 3 regiments were authorised

by this decree, the 2eme Chasseurs a Cheval de la Garde, adopted the title of

‘Hussard-Ecaliaruers de la Jeune Garde’, and adopted a new shako.

In the French cavalry of the period, Light cavalry did not act en mass as skirmishers like

the Russian and Polish Cossacks, but instead sent out individuals or parts of company’s as

skirmishes. The Eclaireurs acted as mounted skirmishers, and operated in pairs, and negated

the need to break up a cavalry regiment or squadron, acting as Napoleon wished, as

mounted Voltigeurs. The musketry from such a cavalry skirmish line does not appear to have

been organised into volley fire, but was voluntary.

If one takes Napoleon’s instructions literally the scouts would act as mounted voltigeurs,

who would ride up to a line at the gallop, halt, fire a volley and then withdraw again at the

gallop to re-load, constantly harassing the enemy, and breaking it down by picking off officers

and NCO’s. However, the second rank did not fire, and held its fire to defend the front rank

if attacked. Parquin in his memoirs recalls the following incident:

However, carbines, and firearms in general were considered to be a poor second to the

sabre as far as most cavalry commanders were concerned despite their obviously crucial benefit

in such instances as cavalry versus infantry squares or even against enemy cavalry.

Well armed light cavalry were full of potential that had yet to be properly cultivated and developed.

Regulations stipulated that all manoeuvres were controlled at the gallop, which

quickly wore down horses, which were in very short supply to the French in the closing years

of the Empire.

The Eclaireurs, like the Russian Cossacks exploited a weakness in contemporary

cavalry tactics. Perhaps this is why the scouts adopted Light Infantry tactics. If regular cavalry

was not supported with either infantry or another cavalry regiment, and faced with

equal numbers of light skirmishing cavalry, the tactics were unable to deal with these troops.

For example at Luckenwalde in August 1813 a French Cuirassier regiment was

attached by Russian Cossacks, who enveloped the Cuirassiers flanks and rear and were not

able to free themselves from the Cossacks, until a second cavalry regiment came up.

However, if attacked a Cossack unit could be stopped and overrun by a smaller opposing

force of regular cavalry. The Eclaireurs combined the best elements of the regular French

Light Cavalry and Russian Cossacks units.

The Eclaireurs also fulfilled other roles. Heavy and light cavalry often co-operated in

the field, and was a tactic that had been employed earlier by the Russians. The heavy

cavalry would be screened by the light cavalry, at Borodino, three cuirassier and four dragoon

regiments moved forward with a light cavalry screen, when the attacked was pressed

home, the heavy cavalry would attack in front and the light cavalry the flanks. In essence,

each regiment of Guard Cavalry became a self contained cavalry corps of three regiments, of

heavy, medium and light cavalry, which would often operate in unison. In essence the

guard cavalry by 1813 had become a self contained army corps.

These new tactics are a significant change from earlier tactics where

all heavy cavalry acted together, all medium cavalry and all light cavalry, creating homogenous

cavalry brigades. The line cavalry retained these old formations, having pure

heavy and light cavalry formations. The Eclaireurs also acted as the eyes and ears of

the army, by scouting ahead of the army.

Tactical doctrine of the period stated that a cavalry commander should never order a

charge or movement to the front without having previously sent out skirmishers to ascertain

whether there was some obstacle which had not been observed. This rule was frequently

ignored in battles, but proved invaluable when moving an entire army, as any

obstacle be it natural or enemy troops, could prove costly in time and men. It was felt that

scouts should be always within a pistol shot of the enemy, and be well mounted.

With the formation of the Eclaireurs, the composition of the guard cavalry was changed:

2eme Division: General Exelmans

3eme Division: General Letort

The Eclaireurs charged at Craonne on 6/7th march 1814, where several members of

the 1st regiment were decorated with the star of the Legion d’Honneur. Colonel Testot-Ferry,

who charged with at the head of his 1st Eclaireurs, was made a Baron of the Empire.

The Eclaireurs were engaged on the 12th march against the Russians at Rheims, and

again on the 26th where Napoleon sword in hand lead the charge of the guard cavalry.

The Eclaireurs were disbanded on 24th June 1814, but they had proved to be useful

formations. Napoleon instructed on 15 May 1815 the creation of a regiment of Eclaireurs-Lanciers,

which was to be attached to the corps of Chasseurs a Cheval of the old guard,

and to be administered by the corps.

Article 11 of the decree stipulated that the regiments

uniform was to be a habit, in the same colouring as the chasseurs a cheval of the guard. This

rather strange regiment was not formed, as 10 days later, the emperor decided to form a

second regiment of Chasseurs a Cheval. Also considered was a unit of Tirailleur a Cheval,

literally mounted skirmishes, perhaps better fitting the scouts role than the designation scout.

After the fall of the first Empire, the French Army was to re-organised. With a

view of destroying all links with the Napoleonic period, Louis XVIII disbanded all the

old regiments and eradicated their traditions, and established the Legion Departmentals.

The Royal decree of 3rd August 1815 created 86 departmental legions. Each Legion was to

be composed of two battalions in 8 companies, two of which were classed as elite, one

being Grenadier the other Voltigeur, as well as a battalion of Chasseurs of eight companies,

three of which were depot companies. Attached to each Legion was a company of Artillery

and a company of Eclaireurs a Cheval.

In theory, each Legion consisted of 103 officers and 1,524 men. The Legions were suppressed

by the Royal Decree of 23rd October 1820 when the old regiments were reformed.

Eclaireurs de la Garde Imperial

|

The Guard cavalry was formed in 1799 with a regiment of heavy cavalry, which

became the Grenadiers a Cheval and a regiment of Guides, which became the

Chasseurs a Cheval. In 1806 a regiment of Dragoons was added, and in 1807 a

regiment of Light Cavalry formed from the Polish Nobility, with the addition of a

second Lancer unit from Holland in 1810.

The Guard cavalry was formed in 1799 with a regiment of heavy cavalry, which

became the Grenadiers a Cheval and a regiment of Guides, which became the

Chasseurs a Cheval. In 1806 a regiment of Dragoons was added, and in 1807 a

regiment of Light Cavalry formed from the Polish Nobility, with the addition of a

second Lancer unit from Holland in 1810.