Battle of Jemappes

6th November 1792

Long Term Effects

by Dave Hollins, UK

| |

The impact of this battle was both immediately extensive and long-lasting. Revolutionary France had taken the offensive and grabbed a rich part of the Habsburg Empire, but the Volunteers of 1792 now felt they had done their year’s duty to save la Patrie and as supplies broke down over the harsh winter of 1792-3, many melted away and dramatically weakened the Nord. When the spring came, the Austrians had regrouped under FM Josias Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld and returned to the offensive. In the more equal battle of Neerwinden on 18th March 1793, Dumouriez attempted to repeat his Jemappes tactics, but found his left ripped apart by Smola’s guns and was forced to abandon the Netherlands to Austria.

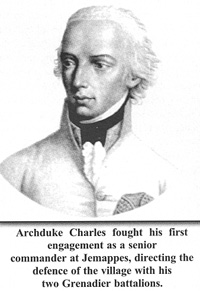

Nevertheless, Archduke Charles had already noted a key problem for the Austrian command, when writing in the Operations Journal just after Jemappes – the Hofkriegsrat (Military Administration) in Vienna was simply not effective in its tasks of supplying and directing the armies. Communications from them, which attempted to direct the army’s strategy, were too slow. Archduke Charles fought his first engagement as a senior commander at Jemappes, directing the defence of the village with his two Grenadier battalions. It is also interesting to note that the commander of the French 1er Hussards (formerly Bercheny) was colonel Armand Nordmann, an Alsatian, who led two squadrons in emigrating to join the Austrians early in 1793 and would die as an Austrian Feldmarschalleutnant at Wagram in 1809 In Paris, the battle had given a big impetus to two ideas: The first, proclaimed in late 1793 by the Jacobin Delbrel, was that “Every time we have attacked, we have won and … every time we have been attacked, we have almost always lost”. French armies were to assume the strategic offensive. Alongside this policy, the French infantry would increasingly advance in attack columns formed en echequier (chessboard fashion). However, it was clear even at this early stage that such a tactic required well-trained troops to deploy under fire – the author Lynn believes Jemappes is the only case where the Nord deployed into line at close range. This battle had demonstrated that less well-trained troops could not deploy properly, a French weakness spotted by the Austrians and their Chief of Staff, Karl Mack, would note it in his 1794 Instructions. This failure led to the mistaken growth of the cult of the bayonet – a belief that over the last 50 paces, lowered bayonets would scatter the enemy without the need for a tricky firefight. From 1803, French troops would again be well trained enough to deploy from these columns, but as their army had to resort to less well-trained troops after 1806, they reverted to the belief in the impetus of the column, augmented by several artillery pieces at the front, to spearhead an increasingly large battering ram, to carry it through the enemy line. However, as Allied gunners tore into these columns from Neerwinden onwards, the casualties rose while the impetus of these attack columns failed to break through. Once Allied lines held, both in central Europe and Spain, the groups of attack columns were useless – if they failed to break through, the men would be mown down by enemy guns and steady infantry. It seems quite ironic that just 30 miles north-east of Jemappes (unfortunately now ruined by strip-mining), lies Waterloo, where 23 years of war ended. There, Napoleon would direct Drouet d’Erlon (a senior commander in the centre at Jemappes) to launch one last massive infantry assault uphill at the British line in June 1815, but it famously failed. In Swords Around a Throne, Colonel Elting wonders on p.537 about the explanation for the shape of this column – a 175 man frontage (in other words, a French battalion formed three ranks deep) so that the formation was already deployed in line with the weight of a column behind it. The need to be in line was in response to the formed Allied lines of musketry, but above all a recognition that at Jemappes, it was the failure to deploy properly, which had caused so many problems for the French, who then had to sustain heavy casualties while in two-peleton frontage columns. The problems of column attacks were already visible 22 ˝ years before the last column fell to linear tactics. SourcesKriege gegen die französische Revolution (1904-5) Vol.2 pp.242-7 and

Appendices – this Staff History’s authors used Austrian

documents and Jonquiere: La bataille de Jemappes.

E. Desbričre: La Cavalerie pendant la Révolution du 14 Juillet 1789 au 26 Juin 1794, Cavalerie Iie Fascicule (Paris / Nancy 1907) J.B. Schels: Des Herzogs Albert von Sachsen-Teschen Königliche Hoheit Vertheidigung der Niederlande im Jahre 1792 (OMZ 1811-1812) I should also like to thank Terry Crowdy and Hans-Karl Weiss for their assistance. For uniforms of the troops involved, see the Osprey Men-At-Arms series:

D. Hollins: Austrian Auxiliary Troops 1792-1816 (MAA299) P. Haythornthwaite: Austrian Army of the Napoleonic Wars (1-3) (MAAs 176, 181 & 223) Battle of Jemappes 6th November 1792

Armies Take Position The French Attack Long Term Effects Order of Battle: Austrian Order of Battle: French Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire # 77 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 2004 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com |