The Siege of San Sebastian

July 10th - August 13th 1813

Preparations

by Leon Parté, UK

| |

The Siege of San Sebastian was the last of the many sieges of the Peninsular War. It was a long and protracted affair. The first serious assault failed, though the second proved successful, although it was more by good luck than good management happy accident. The chance ignition of a quantity of explosives behind the French line of defence, which tipped the balance just as the British stormers were in danger of a second defeat. Finally, capture was followed by pillage and a series of atrocities and cruelty which, as Napier puts it, “staggers the mind with its enormous, incredible, indescribable barbarity.”

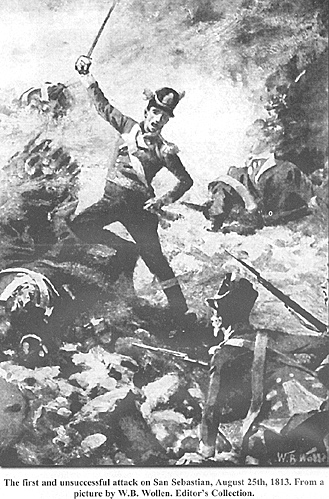

The first and unsuccessful attack on San Sebastian, August 25th, 1813. From a picture by W.B. Wollen. Editor’s Collection

Discipline disappeared in universal drunkenness. The men when checked chased their officers away with volleys. A Portuguese adjutant who dared to interfere was put to death by a party of English soldiers. The sack did not cease until a general conflagration, following in the footsteps of the brutal soldiery, completely destroyed the town.

Wellington’s New Port

The possession of San Sebastian, or of some good seaport upon the Bay of Biscay, became necessary to Lord Wellington in the closing campaign of the Peninsular War. When

he left Portugal to march across Spain, driving the French before him he abandoned his only base of supply at Lisbon. A new and nearer port was now needed; a harbour at which food, stores, and reinforcements coming from England could be landed, and by which he could keep up his direct communication with home. San Sebastian was the most convenient for Wellington's purpose, and, cost what it might, San Sebastian he meant to have. He made no secret of this determination, and his anxiety no doubt stimulated those entrusted with the siege -- for Wellington was not constantly present --- to premature efforts in an unwise departure from the instructions he gave. Had the plan of which he approved been followed exactly, history would not have recorded the delays, disappointments, and disasters, which have made San Sebastian memorable among the sieges of Spain. Wellington wished to lose no time in gaining the fortress, but he still wished it to be besieged according to rule. Sir Thomas Graham, who was in chief command, although one

of his ablest lieutenants, was sometimes over persuaded to take steps which caused costly expenditure of men and material.

San Sebastian in 1813

San Sebastian is now occupies the whole frontage of its spacious bay. In 1813 it was limited to the low peninsula running north and south, on which stood the small town surrounded by its fortifications. These defences to the landward or southern side of the isthmus were the more important, and consisted of a high rampart, 350 yards in length, at each end of which were half-bastions giving flanking fire along the ditch. In the centre of the rampart a bastion stood out to the front, and in front of that again was a more advanced fort, called a horn-work, covered by a ditch and glacis. East and west of the town the only defence was a simple wall, indifferently flanked and unprotected by obstacles in front of it, for waters washed its base, to the westward of those of the sea, to the eastward of the River Urumea, a tidal shallow stream that ebbed twice daily, leaving exposed a long, firm strand. The latter undoubtedly constituted the weakest part of the fortress, and it was within full view and easy reach of high land and commanding sand-hills, called the Chofres, on the far side of the river.

San Sebastian had a second and a third, an outer and an inner, line of defence. The first was the high ridge called San Bartolomeo, which crossed the isthmus at its neck, the other was the rocky height of the Monte Orgullo, or “Mountain of Pride,” that rose steeply north of the town at the end of the peninsula. San Bartolomeo had been fortified directly the siege became imminent. A redoubt was constructed on the plateau connected with the convent buildings, and this redoubt was supported by a second made of casks nearer the town, and by strengthening the houses in the suburb just under the northern ridge of San Bartolomeo and on the inner side of the ridge.

Monte Orgullo was crowned by the castle of La Mota, a small-enclosed fort with batteries on each flank, the whole raised on such an elevation as to command the town and the

isthmus beyond. La Mota formed the citadel and key of the defence.

Rey's Preparations for Siege

The possession of San Sebastian became of greater importance after Vittoria, and General Emanuel Rey entered the place, determined to hold it at all hazards. Rey was a man

of strong, soldier-like character, and his somewhat harsh, overbearing demeanour was accompanied by indomitable energy well suited to the present crisis. He was, like Philippon of Badajoz, and many other French governors of fortresses, the product of Napoleon's famous ordinance that a place of arms must never be surrendered until it has endured at least one open assault.

Rey strained every effort to reconstitute the fortress and develop its resources. The war commissary was sent off to Bayonne in an open boat, braving the English cruisers, to beg for substantial help. San Sebastian itself had been nearly dismantled. Many of its guns had been removed to arm other smaller places along the coast. It was short of ammunition, food was scanty, the wells were mostly foul, brackish, and thick with mud, and an aqueduct, which was soon cut off by the besiegers, supplied the only fit drinking water.

Fortunately for the French, the British blockade in the Bay of Biscay was ineffective, and sea communication was maintained between the fortress and Bayonne almost to the end of the siege. In this way munitions of war, reinforcements, food, and all other necessaries were constantly received. Rey set his garrison, which was now being strengthened by the arrival of fresh detachments ments, to work on the fortifications. It was now that the redoubt was built on San Bartolomeo; the bridge across the Urumea was burnt down; and as guns were received the batteries were armed and strengthened.

When the siege actually began Rey could dispose of 76 pieces of artillery: 45 were in the main works, 13 on Monte Orgullo, 18 were held in reserve. The number of artillerymen

was insufficient, so detachments of infantry were instructed in gun drill. The garrison was without bombproof cover, and was very exposed; so were the magazines.

Another drawback, which Rey dealt with in peremptory fashion, was the non-combatant population. Refugees from Madrid had crowded San Sebastian, the fugitive grandees

of King Joseph's Court, and these helpless people -- all useless mouths -- were promptly expelled.

Reconnoitre by Wellington

Wellington, accompanied by his senior engineer officer, Major Smith, reconnoitred the place on July 12th, and with him concerted the plan of operations. The conduct of the siege

was given to Sir Thomas Graham who had under his orders the 5th Division of British troops, two brigades of Portuguese, some blue-jackets from H.M.S. Surveillante , and a party

of sappers and miners. The first occasion on which these valuable soldiers were employed in a siege in Spain. The total force amounted to 10,000 men, being about three times the

strength of the garrison. Forty pieces of artillery were available, part of them belonging to the battering-train prepared for Burgos, the whole train being under the command of Colonel

Dickson, a favourite artillery officer of Wellington.

The weakest part of the defences, a point in the eastern wall of the town, was to be breached. When the breach was formed, the assault was to be delivered, the assailants advancing at low water between the walls and the river. It soon became clear that the San Bar- tolomeo ridge must be wrested from the enemy, for its guns would have greatly harassed the attacking columns. The capture of San Bartolomeo was accordingly the first enterprise undertaken. It was bombarded, then attacked on the morning of July 17th by two columns -- one of British, the other of Portuguese troops.

The latter moved slowly. Colonel Cameron, leading the 9th and Royals, raced forward and charged with such impetuosity that the French were driven straight out of the redoubt. Down below in San Martin they rallied, but Cameron being reinforced the suburb was presently won. The cask redoubt beyond was next stormed, but without success. It was, however, taken a couple of nights later.

The Siege of San Sebastian July 10th - August 13th 1813

|