Netherlands Artillery

in the Waterloo Campaign

Part I: The Artillery Arm in the

Kingdom of the Netherlands

by Geert van Uythoven, The Netherlands

| |

Events unfolded at a fast pace when Napoleon returned to France. Without waiting for the outcome of the Congress of Vienna, on 16 March 1815 the Prince of Orange proclaimed himself King William I of the Netherlands, Prince of Orange-Nassau, Duke of Luxembourg. On 1 April the armies of the Southern and Northern Netherlands were united, and on 21 April the units were renamed as in the table. "A sergeant of the horse artillery in full dress, painting by Hoynck van Papendrecht" Therefore, from this date on there was officially no difference anymore between northern and southern units. However, until this day the difference is still made by many, and therefore I will continue this at the appropriate places beneath. On 17 March 1815, the day after the Prince of Orange had proclaimed himself King William I of the Netherlands, it was decreed by Koninklijk Besluit No.1 that thirty infantry battalions, ten cavalry squadrons, and ten artillery batteries would be mobilised to form a ‘Netherlands Mobile Army’ of three infantry Divisions. The Indian Brigade (consisting of troops destined for the West- and East-Indies), and three cavalry brigades (on 21 April united into a cavalry Division), which would be part of the Anglo-Allied army to be commanded by the Duke of Wellington. 5

To be complete; on 24 May 1815 it was decided to create a Reserve Army, to reinforce the Netherlands Mobile Army later in the campaign. Part of this Reserve Army would be three foot artillery batteries, and a horse artillery battery. The Reserve Army came into being only partially after the battle of Waterloo, without any artillery, and it did not participate in any fighting.

6

At first glance it may be a somewhat strange occurrence that ten artillery batteries would be ‘made mobile’, as it implies that most artillery was not made mobile, and thus could only serve in a static role within fortresses etc. In fact this really was the case! At this time in the Netherlands all artillery was regarded ‘fortress-artillery’, which mend that all artillery companies were in garrison. Of the sixteen of

those ‘artillery-garrisons’, i.e. fortresses with one or more artillery companies, that existed, only seven also had a train detachment in garrison, which mend that most of the artillery companies were not able to practice with horse teams.

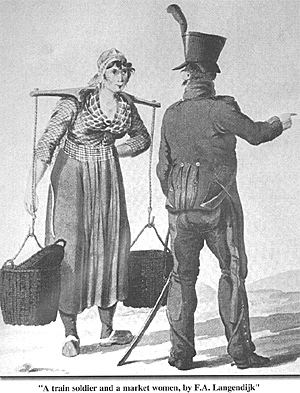

So at that time the Netherlands artillery could not be regarded as being proper ‘field-artillery’. This was indeed even the case for the horse artillery, of which for the northern part as we have seen already on 8 February 1814 it was decreed that only two batteries would be made mobile for use in the field, to be assigned to the cavalry. The companies of the horse artillery that were not made mobile served on foot, the same way as all other foot artillery companies. The downside of the system of ‘making mobile’ artillery batteries at short notice became clearly visible during the Waterloo campaign.

Therefore, after the campaign six batteries were ordered to remain mobile at all times, while all other artillery companies had to return their material and equipment to the magazines, and returned to the various fortress-cities to resume their static role as ‘fortress-artillery’.

The procedure of making mobile a battery was as follows. First, artillery companies were organised and brought up to strength, which were to serve artillery batteries. When, at will, such a company was order to make mobile an artillery battery, it was directed to the magazine in Delft were it received eight guns on carriages, with limbers and the necessary wagons, the latter consisting of loaded ammunition caissons and baggage wagons, everything with the necessary tools and other equipment. At the magazine the artillery company waited for the arrival of a detachment of the train under the command of a lieutenant, who brought the necessary horse teams. The company was usually known by the name of its (1st) captain, and when made mobile, it was known as the battery named by

its captain. For example, a company of the 4th Line artillery battalion was commanded by Captain E.J. Stevenart, and as such known as the Foot artillery company ‘Stevenart’.

After being made mobile, it became the Foot artillery battery ‘Stevenart’. When Stevenart was killed at Quatre-Bras and his company decimated Captain van Steenberghe with his own company,

also of the 4th line artillery battalion, received on 30 June orders to take over the battery from the survivors. From that moment on, the battery ‘Stevenart’ ceased to exist. Another thing that should be noted, is that artillery companies that had not been made mobile were named vesting-artillerie, i.e. ‘fortress-artillery’. Because of translation errors, some of such companies that were attached to the artillery

parks later during the campaign are listed in some sources as ‘siege artillery’, or d’artillery de siege. This could give the wrong impression, although these companies could have been used for serving artillery pieces captured inside French fortresses, to besiege other fortresses still resisting to the Allies.

Each of the three infantry Divisions would have a foot artillery battery attached to each of its two brigades, while the three cavalry brigades in the cavalry Division would receive two half horse artillery batteries only. In addition, an artillery reserve would be formed of the remaining batteries, including the necessary horse teams and able to take the field. It was hoped that finally twelve or thirteen batteries

could be made mobile, i.e. ten of the former northern, and two or three of the southern Netherlands. Everything possible was done to reach this goal. Already on 16 March Colonel D.E. Bo(o)de, who was director of the 4th Artillery Direction 7 , had dispatched orders to load the caissons of the six additional batteries that would be made mobile; two in Breda, three in ‘s Hertogenbosch, and one in Bergen-op-Zoom.

The horses however were still an enor-mous problem: on 25 March only three batteries had enough horse teams to take the field! These were the Foot artillery battery ‘Scheffer’, and the Horse artillery batteries ‘Petter’ 8 and ‘Bijleveld’. This did however not mean that these were on full strength: Horse artillery battery ‘Petter’ was on this date still 56 horses short, while Horse artillery battery ‘Bijleveld’

needed an additional 140 horses! To add more artillery to the mobile army, a battery served by the 3rd company of the 5th ‘East-Indian’ Line artillery battalion, commanded by Captain C. J. Riesz, destined for the colonies in the East Indies, was attached to the Indian Brigade. 9

The 1st Division received Foot artillery battery ‘Scheffer’ 10 which was still at Namur. For the time being the Division would be one artillery battery short. The 2nd Division would receive a foot artillery battery that was made mobile in ‘s Hertogenbosch. For the time being, in order not to leave this Division without artillery entirely, Horse artillery battery ‘Bijleveld’ was assigned to it, to be transferred to the artillery reserve later. This never happened because of the lack of batteries. The 3rd Division would receive a ‘southern’ battery armed with 12-pdr cannon, or 6-pdr's that would have to be obtained from Breda. The Horse artillery battery ‘Petter’ would be divided over the three cavalry brigades. This was all that was available right now.

In the south the situation was even worse. As we have seen, Captain C.F. Krahmer de Bichin was busy forming a horse artillery battery, while Captain E.J. Stevenart was forming a foot artillery battery. It was hoped to raise a third (foot) artillery battery later. As there were no field guns available, personnel of the southern artillery companies and train soldiers were on 29 March ordered to go from Mechelen to Breda, to obtain the material and equipment for two 6-pdr batteries. The Horse artillery battery ‘Krahmer’ was ready first and attached to the 3rd Division which still was without artillery at

all. So because of the lack of foot artillery batteries, two infantry Divisions now had horse artillery assigned. To remedy the lack of foot batteries, on 18 March the 2nd (northern) Line artillery battalion was ordered to make mobile four of its six companies:

The remaining 2nd and 6th companies (‘Scher(r)er’ and ‘Overreitn’) moved to ‘s Hertogenbosch, to form the depot for the batteries that were in the field. The commanding officer of the 2nd Line artillery battalion, Lieutenant-Colonel G.J. Holsman, had been ordered to Louvain to supervise the making mobile of both batteries of the artillery reserve. He would be subordinate to Colonel, later Major-General C.A. Gunkel, commander of the artillery of the mobile army.

So on 12 June 1815 the Netherlands mobile army had nine artillery batteries with its field army in the southern Netherlands, with a total of 72 officers, 2,524 others, and 2,559 horses. Of these however, only seven were fully made mobile and with enough horses. With the mobile army about 31,000 men strong, this meant 1.8 guns for every thousand men, while at that time the Netherlands army had 2.5 gun for each thousand men as the standard. Especially for a raw an untrained army as the Netherlands army was at that moment, this was a serious disadvantage. The 1st Division was still one artillery battery short; both batteries in the artillery reserve as we have seen were without enough horses. Of the intended ten ‘northern’ and two ‘southern’ batteries, five were still not fully mobile: Foot artillery battery

‘Kaempfer’, for the time being with the reserve, would take the field first as it would be the first one mobile; the 12-pdr Foot artillery battery ‘Du Bois’ and three more batteries still in the province of Noord-Brabant were still without any horses and not able to take the field yet. 11 The assignment of the batteries present with the Netherlands Mobile Army were as follows [officers/others/horses](‘N’ = ‘northern’; ‘S’ = ‘southern’):

Commander in Chief: His Royal Highness the Prince William of Orange

Indische Brigade (‘Indian Brigade’ Lieutenant-General C.H.W. Anthing)

1ste Divisie (Lieutenant-General J.A. Stedman)

2de Divisie (Lieutenant-General Baron H.G. de Perponcher Sedlnitzky)

3de Divisie (Lieutenant-General Baron D.H. Chassé)

Cavalerie Division (Lieutenant-General Baron J.A. de Collaert)

Reserve-artillerie (Lieutenant-Colonel G.J. Holsman)

Park (Lieutenant-Colonel J. de Frees)

The park consisted of the following: a director; two 2nd captains or 1st lieutenants; two clerks; a custom-house officer, an aide-surgeon and an élève-surgeon, one captain-commander of the field train; a foot artillery company; artificers in wood and iron; a horse veterinary surgeon, and harness makers. Each day the Netherlands units exercised, to bring training up to an acceptable standard as soon as possible. However, this was still not completed when hostilities began. Only on 4 June for example, the Prince of Orange made clear his intentions to concentrate the 3rd Division on the fields near Casteau village, in order to train manoeuvres on a higher level (i.e. brigade and Division).

The first manoeuvre was planned for 8 June, but because of safety reasons (the French threat which was materialising, and it would bring the Division too far west) it was cancelled. From the next day on, the Prince of Orange ordered that every unit should be under arms early each morning, until evening when everything was still quiet. The artillery would have to be under arms in the park from 05.00 p.m. until 19.00 a.m.: “If there are no further orders, the commanders of the companies may dismiss their respective batteries at 7 hours”. During these fourteen hours, to be changed at noon, half of the horse teams should be in the park, the other half harnessed in the stables. It should however be noted that the train detachments were not always cantoned in the same places as their respective batteries! It should also be noted that the artillery was formally part of the Divisions, not of specific brigades with the exception of the Indian Brigade. Hence the appointment of Divisional commanders of artillery.

In practice though the batteries were attached to the brigades within the Division, although at Waterloo, both batteries of the 3rd Division (‘Lux’ and ‘Krahmer’ acted directly under the direction of the Commander of the artillery Major J.L.D. van der Smissen. All artillery batteries had 8 guns; six 6-pdr cannon, and two 24-pdr howitzer. The only exception was the Foot artillery battery ‘Du Bois’ of the

reserve, which had 12-pdr cannon. 14

The batteries were divided in ‘sections’; three cannon- and one howitzer-section. But they could also be divided in two ‘half batteries’, consisting of three cannon and a howitzer each, each commanded

by the most senior lieutenants with the battery. In many instances the artillery batteries operated in separate sections or half batteries, and not as a whole, according to the circumstances. For example Lieutenant Winssinger’s section during the battle of Quatre-Bras, and Captain Krahmer’s half batteries at Waterloo.

Netherlands Artillery in the Waterloo Campaign 1815 Part I

Netherlands Artillery in the Waterloo Campaign 1815 Part II: Artillery Officers

|