Netherlands Artillery

in the Waterloo Campaign

Part I: An Artillery Arm is Raised

in the Northern Netherlands

by Geert van Uythoven, The Netherlands

| |

At right, author van Uythoven. After the arrival of a few hundred Cossacks in Amsterdam, on 17 November 1813 the ‘Vereenigde Nederlanden’ (‘united Netherlands’) declared themselves an independent nation, throwing of French yoke. 1

In fact, it was only a proclamation by three men. And this was a bold move to do, at a moment that numerous fortress cities in the Netherlands were still occupied by strong French garrisons. Many inhabitants were reluctant to support the self-created government. The arrival of a handful of British Marines in The Hague, followed by His Royal Highness Willem Frederik, Prince of Orange, who landed

in Scheveningen on 30 November, decided the issue in favour of the new nation.

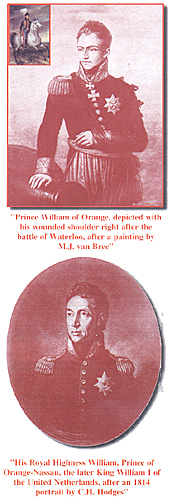

His Royal Highness William, Prince of Orange-Nassau, the later King William I of the United Netherlands, after an 1814 portrait by C.H. Hodges

Prince William of Orange, depicted with his wounded shoulder right after the battle of Waterloo, after a painting by M.J. van Bree

One of the first acts of the Prince of Orange, now Sovereign of the Vereenigde Nederlanden, was to decree some kind of Levée en masse (6 December 1813), which should provide for an army of 16,000 infantry and 4,000 artillery. An important act; the existence of an independent Netherlands nation would only be granted by the Allies when this young nation could contribute to the war efforts against

France, now and in the future. Although it was pointed out to the inhabitants that the task of this army would be to free the country from the French still present, the effort failed miserably. Not only were many families were still mourning the loss of their sons, of which thousands had perished in the Russian snow. Many officers and others with military experience were dispersed over the whole of Europe and indeed the whole world, in exile, as prisoners of war, or still serving in French or Allied armies. In the long term this manpower would become available, but not yet.

On 9 January 1814 followed another decree, which laid down the organisation of the Netherlands army, which not surprisingly was build up according to the French organisation. For the artillery, it was stipulated that there would be 4 foot artillery battalions (‘artillerie te voet’) of the standing army, eight companies and a staff each. In addition, there would be a horse artillery corps (‘Korps rijdende

artillerie’) also of eight companies. Also, a battalion of artillery train (Bataljon trein) of six companies would have to be formed.

Finally, to be complete, four militia foot artillery battalions (‘artillerie te voet landmilitie’) of eight companies each and a staff would be raised.

On 8 February 1814 it was decreed that the magazines would have to prepare ten artillery batteries for the field army, to be served by artillery companies. Of these batteries, eight would be armed with 6-pdr cannon, of which two would be served by the horse artillery; the remaining two foot artillery batteries would be armed with 12-pdr cannon, to be served by foot artillery companies. The amount, composition and armament of these batteries was influenced by the material available for use in the field. As there was no specific horse artillery equipment available, the horse artillery batteries had the same equipment etc. as the foot artillery; the only difference was that in the horse artillery the gunners were mounted, while in the foot artillery they were not.

From early 1814 on, the Netherlands army began to take shape, although process was slow. On 1 April 1814, of the over 6,500 men needed for the artillery only 3,600 were present, still a shortage of 2,900. The reason for this has already been pointed out. Especially officering the units was a problem. There were three sources available. A great number of former officers of the army of the Dutch Republic of before 1795, which did not see much or completely no active service since then, came forward to offer their services. Being of the old Orangist core which never had ceased to support the cause

of the House of Orange they could not be ignored, especially because at that moment no other officers were available. And because of their high age they all had to be considered for high commands.

Secondly, French military personnel of Netherlands origin that had been taken prisoner by the Allies were gradually released and joined. Especially after 30 May 1814, after the Treaty of Paris had been concluded, Netherlanders in French service received their discharge and most of them immediately applied for a new commission in the Netherlands army. Lastly, many young men which had in 1813 taken the lead in the rising against the French had to be rewarded for the efforts, receiving the rank of lieutenant or captain. Although highly motivated, most of them had little or no military experience, and now received the difficult task to raise and train their own units.

Captain Lux is a clear example of this. The return of officers that had been in French service finally gave the Netherlands army a core of experienced officers and NCO’s. At the same time, officers that had not the right qualities for a field command were pensioned or received static posts inside fortresses, were they could do not much harm for now. Until this moment, the artillery was in a sorry state, but with experienced officers and NCO’s arriving every day, the first artillery batteries were soon at a level that they were usable in battle.

On 14 March 1814, Prince Frederick of Orange was appointed Grand Master of Artillery, while Major-General Du Pont was appointed General-Inspector of the same arm. Already as early as December 1813, former Captain M.A. Kuytenbrouwer 2 who lived in the city of Utrecht was charged with raising a Horse artillery corps in that city. On 22 January 1814 by decree a number of officers were enlisted in the horse artillery, among them the Captains A. Petter, A. Bijleveld, and A.R.W. Gey, all having been in former French service, which we will meet again. As the biggest threat for the young nation came from the south, most artillery magazines for the field army were in the south in the province of Noord-Brabant. So not surprisingly, after a few months the horse artillery depot moved to the fortress-city Breda in this province. Of this corps, as far as is known, the 7th and 8th companies were never raised.

On 1 April 1814, the strength of the Horse artillery corps was fixed on six instead of eight companies. On 17 November 1814, before the army of the Northern Netherlands was merged with that of the Southern Netherlands, the artillery had reached the following strength [officers/others]:

Artillerie te voet landmilitie: four battalions, each of six companies, a total of 24 companies [128/2,952]. Strength of a battalion was the same as for the foot artillery battalions;

Korps rijdende artillerie: six companies [35/723]. Strength of the corps was 35 officers and 729 others. In peace time, it had 408 horses, 640 in times of war; -

Bataljon trein: six companies [17/468]. Strength of a train battalion was in peace time 17 officers, 468 others, and 468 horses. In times of war, strength was 23 officers, 943 others, and 1,629 horses. Netherlands Artillery in the Waterloo Campaign 1815 Part I

Netherlands Artillery in the Waterloo Campaign 1815 Part II: Artillery Officers

|

The Creation of an Artillery Arm

The Creation of an Artillery Arm

Quickly units of volunteers were raised, augmented with foreigners, mainly Prussians of the 4e Régiment Etrangers, which defected from the French. For the artillery this did not mean much; although cadres could be provided for foot artillery companies up to a total of 1,000 men, a horse artillery corps, and a battalion of artillery train, the gunners themselves were not present.

Quickly units of volunteers were raised, augmented with foreigners, mainly Prussians of the 4e Régiment Etrangers, which defected from the French. For the artillery this did not mean much; although cadres could be provided for foot artillery companies up to a total of 1,000 men, a horse artillery corps, and a battalion of artillery train, the gunners themselves were not present.