Battle of Vimeiro

21 August 1808

The Battle

by Miguel Freire, Portugal

| |

Photo B - photo taken at the beginning of the XX century and published in Revista Militar of August of 1908 (nº 8, Year LX), it depicts the Centennial of the "Peninsular War" celebrations. The elevation is the settlement and the hill of Vimeiro, seen from West to East.

Troop Adjustments At seven o’clock in the morning, the French army was gathered a few miles from the British advanced outposts. They could not see them and did not know at all about this French movement. [5]

At eight o’clock the British first see the patrols from the French cavalry that were send in all directions. Only at ten o’clock did the French infantry column started to move again taking its positions without letting themselves be seen by the British. At the front was General Delaborde’s division with its brigades in column, to the right the 1st brigade from General Brennier, to the left the 2nd brigade from General Thómieres.

To this division’s rear was General Loison’s division with the same troops disposition: to the right was General eral Solignac’s brigade, and to the left was General Charlot’s brigade. Far back, as reserve troops, came two regiments of grenadiers under General Kellermann's command. The cavalry was divided in two corps, one at the right flank of Brennier’s brigade, and the other marched by Kellermann's reserves.

Junot decided to make the main attack at the centre of the British line with a supporting attack against the northeast flank of the British. Junot´s option of engaging the main effort at the centre of the British line can only be as a result of an inadequate reconnaissance – perfunctory, as Charles Oman says [6] - and a misuse of his cavalry. The cavalry should have tried to identify the weak points of the enemy’s disposition. Wellesley quickly saw that the French attack was different to that which he anticipated and quickly redeployed his forces in order to safeguard the British position.

Wellesley kept Hill’s brigade (1st) to his right side and gave orders to Ferguson’s (2nd), Nightingale’s (3rd), Bowes’s (4th), and Ackland’s (8th) brigades to cross the Ribeira de Alcobrichel, between Vimeiro and Maceira, and head towards the Fonte de Lima path to take a new position.

Ferguson's and Nightingale's brigades deployed and stood side by side between the Ribeira de Toledo, to the right, and the Ribeira de Maceira, to the left, making a right angle with the Fane’s and Anstruther's brigades. Crauford’s brigade went in support of the Portuguese troops that were heading towards the Marquiteira region in order to protect the left flank and, at the same time, the rear.

The French Attack

Thómieres brigade makes the main attack to the centre of the position while Brenier’s brigade, from Delaborde’s division, is sent to take position and attack the northeast flank. The division commander, General Delaborde, stays with Thomiéres. Junot realizing the British movements to reinforce the northeast flank he decides to reinforce Brenier’s brigade. He gives orders to Solignac’s brigade to reinforce that one, while the one from Charlot’s will join the one from Thomiéres, that is, the divisions are cut in half and its brigades are to fight separated by a few miles. Brenier was left with seven battalions to the supporting attack while Junot kept eight infantry battalions and three cavalry regiments to make the main effort on the centre position. This situation did seem to worry neither Junot nor his division commanders that kept marching on in column.

The Main Attack (Scheme 1)

About 2200 French, under Delaborde’s command, launched the first strike. First they were fired upon by skirmishers and upon closing with the British they came under fierce musket and artillery fire that they could not stand against. Charging from positions that granted them good protection, some regiments from Fane and Anstruther launched violent bayonet attacks that made, initially, Charlot’s columns to disintegrate, and then Thómieres columns shortly after.

Having been defeated at the first assault, Junot decided to try a second assault at the very same positions on the Vimeiro plain, but this time he assigned the 2nd grenadiers regiment. Led by Colonel Saint-Clair they marched over the same trails, as used on the first assault and were reinforced by Thómieres’ men who had again regrouped. Once more the violent fire from the British muskets and artillery overcame the French determination, and they could not hold more than half the slope. Junot did not give up and launched his last reserve: the 1st grenadiers regiment, led by Kellermann. He did not follow the line of the other attacks, he decided to follow a trail through a lower hill that allowed him to take the British flank and get to Vimeiro. Not having anyone ahead of him, at least apparently, Kellermann's grenadiers marched up to the Church.

“Now 20th! Now we want you. At them, my lads, and let them see what you are made of”. [7]

The moment had come to the British cavalry to enjoy the success. Led by the Lieutenant Colonel Taylor, the allied cavalry, 240 British and 260 Portuguese, with the British at the centre and the Portuguese on both flanks, charged over the retreating French. Facing the disciplined firing procedures of the French the Portuguese cavalry hesitated and withdrew “and we never saw more of them till the battle was over ”. [8]

On the other hand, the British cavalry goes ahead. They enter the French positions but blocked by an obstacle they lost their impetus, and besides the fact that the French infantry was firing at them, two cavalry regiments, still fresh, charged over them. Now the fight had changed, the aim was to return to friendly lines. With exhausted horses and under fierce fire many did not manage to escape, and

the ones that did, did so thanks to the 50th regiment that forced the French to fall back. The light dragons from the 20th paid for their “baptism of fire” with the life of their commander and many dead and injured.

Junot had definitely committed himself to an assault on the British centre. Engaging all of his units and reserves, he could only hope for a successful supporting attack to make his day.

In order to attack the northeast flank, Brenier had to get to the area around Ventosa. Hoping to choose the best trail, he opted for the longest one. Solignac, who had orders to follow right behind him, was to arrive – with great surprise – to Ventosa before Brennier.

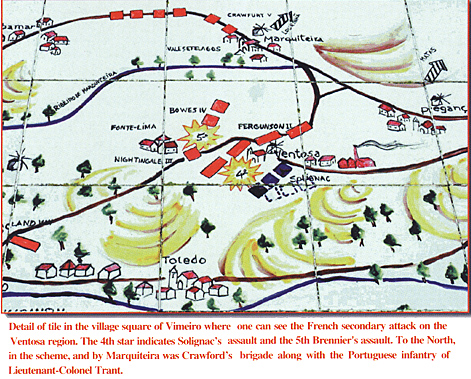

Detail of tile in the village square of Vimeiro where one can see the French secondary attack on the Ventosa region. The 4th star indicates Solignac’s assault and the 5th Brennier's assault. To the North, in the scheme, and by Marquiteira was Crawford’s brigade along with the Portuguese infantry of Lieutenant-Colonel Trant.

When he arrived there, he saw a mere British infantry line at the top of the hill. Solignac, other French generals would later, experience that not what all our eyes see is what really is there. On the reverse slope, were Ferguson’s, Bowe’s and Nightingale’s brigades. When Solignac discovered this concealed deployment it was too late to withdraw, there was no other option but to fight as best they could. Solignac was seriously injured and the French broke and withdrew. Meanwhile, Brenier approaching from the northeast, attacked the British forces that had not pursued Solignac, they were protecting three artillery pieces and were recovering from the attack. Brennier launched an assault and managed to get the artillery pieces, but the British regrouped and were even reinforced. Brennier’s troops befell the same fate as Solignac's!

The End

Junot had exhausted his troops. The Battle of Vimeiro was over and was a clear victory for the British and in particular to their commander, General Wellesley. [9]

Junot withdrew to Torres Vedras leaving Delaborde and Thiébault to gather and reorganise the scattered units, while Margaron, with the cavalry, covered the retreat.

With the French defeat at Vimeiro, a negotiation process began, which would be known has the Sintra Convention. This convention signed on the 30th of August of 1808,

[10] allowed the French, about 26,000 French military personnel, to be evacuated to France in British vessels.

The scandal was such that the three British generals [11] had to justify the process before a court. The Portuguese, who were always kept aside from the negotiations, were not only humiliated and despised by their British allies but also deliberately robbed by the French.

Many details were left unmentioned though they can be read in several works about the Napoleonic campaigns in Portugal, specifically those concerning the first French invasions. More than describing a battle, it is interesting to reflect upon some issues that deal not only with the commanders’ decisions but also with all the military operations “Command and Control” philosophy.

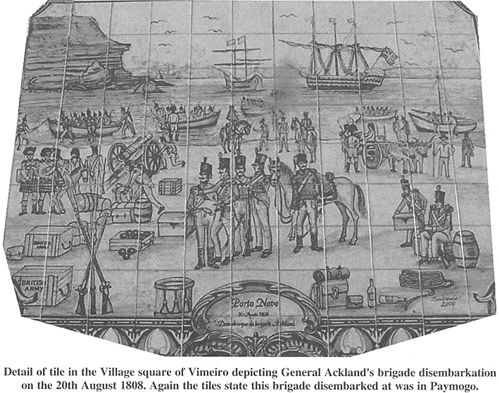

Detail of tile in the Village square of Vimeiro depicting General Ackland's brigade disembarkation on the 20th August 1808. Again the tiles state this brigade disembarked at was in Paymogo. Battle of Vimeiro 21 August 1808

The Battle Junot and Wellesley Chart 1 - British Army Order of Battle Chart 2 - French Army Order of Battle Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire # 70 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 2003 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com |

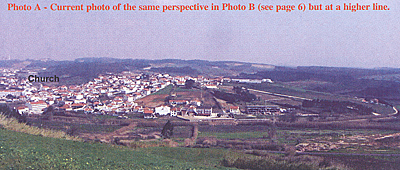

Current photo of the same perspective but at a higher line.

Current photo of the same perspective but at a higher line.

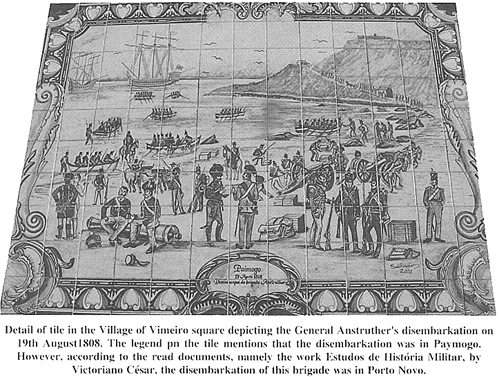

Detail of tile in the Village of Vimeiro square depicting the General Anstruther's disembarkation on 19th August 1808. The legend on the tile mentions that the disembarkation was in Paymogo. However, according to the read documents, namely the work Estudos de História Militar, by Victoriano César, the disembarkation of this brigade was in Porto Novo.

Detail of tile in the Village of Vimeiro square depicting the General Anstruther's disembarkation on 19th August 1808. The legend on the tile mentions that the disembarkation was in Paymogo. However, according to the read documents, namely the work Estudos de História Militar, by Victoriano César, the disembarkation of this brigade was in Porto Novo.

But to their despair, Anstruther had seen Kellermann's troops movement and sent, by his own initiative, the 43rd regiment that struck the French flanks. Ackland having also seen Kellermann's movement decided to move his forces to the centre of Vimeiro from where they also fired at the French. The French grenadiers determination and courage led them a bit forward but the firepower, a consequence of the accurate movement by the British and of their commander’s orders, was so intense that they fell back in disorder.

But to their despair, Anstruther had seen Kellermann's troops movement and sent, by his own initiative, the 43rd regiment that struck the French flanks. Ackland having also seen Kellermann's movement decided to move his forces to the centre of Vimeiro from where they also fired at the French. The French grenadiers determination and courage led them a bit forward but the firepower, a consequence of the accurate movement by the British and of their commander’s orders, was so intense that they fell back in disorder.

The Supporting Attack

The Supporting Attack