First Battle of Biberach

2 October 1796

The 1796 Campaign

by Jens-Florian Ebert and Roland Kessinger, Germany

| |

Moreau’s Crossing of the Rhine The two armies would then unite and continue a joint march to Vienna, while the third attack by the Army of Italy under General Napoleon Bonaparte was originally intended as a diversion to draw Austrian troops from the northern theatre. Bonaparte was ordered to advance to the Tyrol and there make contact with Moreau to support the important operations in southern Germany.

Bonaparte’s victories had both taken large parts of northern Italy and weakened the Austrian armies along the Rhine before the armistice in Germany had even ended. The Army of the Upper Rhine (k. k. Oberrhein-Armee), now under FZM Maximilian Graf Baillet de Latour, was reduced by 26,000 troops. To the north, the Army of the Lower Rhine (k. k. Niederrhein-Armee), was commanded by Archduke Charles, who now assumed overall command of Austrian forces in Germany. Facing.the 67 battalions and 99 squadrons (approx. 50,300 infantry and 16,350 cavalry.) of the k. k. Oberrhein-Armee stood Moreau’s Army of the Rhine and Moselle with nearly 78 battalions and 88 squadrons (approx. 71,600 inf., 6,000 cav.) between Basle and Mainz along the western bank of the Rhine. Once Jourdan had made the initial move, Moreau was to be ready to move across the upper Rhine in late June. The Campaign in Germany and the development of the Corps System

Desaix

Moreau would use this system again four years later, when he commanded the French forces in southern Germany for a second time. During the winter of 1799/1800, Moreau would take command of the Army of the Rhine and promptly reported to Napoleon that he organised it in four corps. Contrary to popular mythology, Napoleon merely acknowledged it and suggested that the left wing Division was also designated a Corps. First Consul Bonaparte did not use this system in his Marengo campaign at all, using only the old meaning of an ad-hoc force detached from the main army. Nevertheless, the introduction of the corps system has wrongly been attributed to Napoleon, whose only contributon was its establishment in peacetime at Boulogne in 1803. Austrian Reaction Knowing of the reduction in FZM Latour’s force, Moreau crossed the Rhine near Kehl on 24th June with a force of approximately 60,000 infantry and 6,500 cavalry. His army had been divided in the four corps. The Austrian commander had more problems than just organising a large army. With all the available forces around Kehl, he tried to prevent a French invasion of southern Germany, but the weak Austrian units in the area supported only by the poorly trained and equipped Holy Roman Empire contingents were quickly driven back. After the successful French crossing of the Rhine, most of these contingents disintegrated, (most of the remains were disbanded on 29th July), forcing most of the Austrian units to escape north down the Rhine. Only a weak Austrian corps under FML Michael Freiherr von Fröhlich (9 bat, 18 sqdns) reinforced by French emigre units under Prince Ludwig Joseph Condé (3 1/2 bat, 9 sqdns) remained south of Kehl in the area around Freiburg im Breisgau on the Rhine. Recognising the very dangerous situation developing in the south, Archduke Charles had handed over command on the Lower Rhine to FZM Ludwig Wilhelm Graf von Wartensleben and hurried south with part of the k. k. Niederrhein- Armee (23 2/3 bat, 39 sqdns including 8 2/3 bat, 19 sqdns Saxon (Imperial contingent) troops) to support Latour. Having joined Latour, Charles fought an indecisive battle around Malsch against the French corps of Desaix and St. Cyr on 9th July.

Operations were now running as Paris had planned: During the first days of July, Jourdan commenced a second and successful French attack on the Lower Rhine against FZM Wartensleben. The combination of Malsch and Jourdan’s renewed advance forced Charles to retreat eastwards, pursued by Desaix and St. Cyr, leaving large garrisons in the fortified cities of Mannheim and Mainz (Mayence) on the Rhine to threaten French communications. Charles’ withdrawal also led to FML Fröhlich and Prince Condé evacuating Freiburg and over the following weeks, they would be pushed by Ferino’s corps towards south-western Bavaria. Archduke Charles’ Decisive Move Throughout most of August, the Army of the Sambre and Meuse was pushing the k. k. Niederrhein-Armee under FZM Wartensleben eastwards. Contrary to the orders of the Archduke, Wartensleben didn’t march to the Danube (in the direction of Ingolstadt), where Charles intended to join him, but in trying to cover his operations base in Bohemia (now the western Czech republic), was leading his troops away from Charles. After a series of indecisive clashes around Neresheim in early August, the Archduke had been concentrating his forces on the south bank of the Danube in Bavaria and could now implement part two of his plan. This he would later describe as: “to contest the enemy’s advance step by step, without being forced into a battle; but to seize the first opportunity to join together the two separated parts of his army and then throw them at one of the two enemy armies” - a classic description of the Frederician “manoeuvre of the central position”, applying a superior force at one point despite an overall numerical disadvantage. Charles knew he had to act quickly. Leaving part of his troops under FZM Latour to keep Moreau busy and to keep the Frenmch southern army away from Jourdan, Charles headed north on 17th August. “Let Moreau advance to Vienna if he can; it matters nothing provided that I beat Jourdan”, the Archduke told latour as he crossed the Danube bridges at Ingolstadt and Neuburg, with 17 battalions and 52 squadrons to reinforce FZM Wartensleben. After driving part of the Army Sambre and Meuse under General de Division Jean Baptiste Bernadotte from Neumarkt in der Oberpfalz (northern Bavaria), Charles sent some troops back under GM Friedrich August Joseph Graf von Nauendorf to reinforce Latour. With the rest of his force – including 8 Grenadier battalions and 38 squadrons – the Archduke continued north and, rejoining Wartensleben, gained an indecisive vic-tory over Jourdan at Amberg on 24th August. From there, Charles drove west to crush Jourdan at Würzburg on 3rd September and drive him on a perilous retreat along the Main River to recross the Rhine at the end of September.

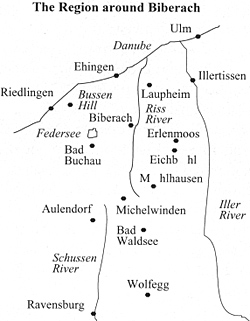

FZM Latour While the fighting rages in the north, Moreau stayed surprisingly inactive, while because of his numerical inferiority, FZM Latour could not attack, despite receiving additional reinforcements from Inner Austria and Galicia. However, Jourdan’s defeat at Würzburg and retreat to the Rhine at the beginning of September exposed Moreau’s position in Bavaria. Too late, Moreau had sent the corps of Desaix and St. Cyr north to support the Army of the Sambre and Meuse. Unable to reach Jourdan in time, they had turned back to the Danube. Despite a small success near Geisenfeld south of the Danube (approx. 15 km southeast of Ingolstadt) against GM Nauendorf, the Austrian reinforcements had joined FZM Latour and pressure was beginning to mount on Moreau from mid-September. Austrian Attacks in mid-September In mid-September, FML Fröhlich, commanding the Austrian troops in the most southern parts of Bavaria (Allgäu) launched an offensive against the division of General de Division Henry Francois Delaborde from Ferino’s corps, driving the French back beyond Ravensburg by 22nd September. At the same time, Austrian troops under FML Franz Freiherr von Petrasch, who had been directed by Charles to interdict Moreau’s lines of communication, began their operations. After Würzburg, Charles had also despatched Oberst (Colonel) Maximilian Graf von Merveldt with 11 cavalry squadrons to Mannheim, where they were to join nine battalions from the city garrison, and support FML Petrasch in clearing the Rhine Valley and cutting Moreau’s communications with France. Petrasch’s troops reached Kehl on 18th September after evicting weak French forces under General de Brigade Marc Armand Elysée Scherb from the Upper Rhine Valley. However, the Austrian forces were not strong enough to storm the French bridgehead of Kehl, so leaving some battalions to blockade the town, the remainder (6 battalions and 14 sqdns) occupied the key Black Forest passes and attempted to make contact with FZM Latour. While Petrasch was operating in the rear of Moreau, a popular uprising broke out in the southern part of Swabia and the Black Forest. During the summer, the French had forcibly extracted “contributions” from the area to pay and support of their army, as part of the terms of the armistices signed by the small Holy Roman Empire states of the Swabian District with the French Republic in August 1796. These extortionate contributions turned the German population against the “liberating” French, so many peasants were ready to take up arms in September and support the Austrians against the French. The peasants were organised by Austrian representatives into a Landsturm, (militia). These armed peasants quickly rendered all the roads between the southern part of Swabia and the Upper Rhine unsafe. French soldiers, wounded, wives and children of French soldiers, and merchants, who travelled alone or in small groups were attacked, wounded and often killed. Many supply convoys and artillery trains were stopped and plundered, sometimes in co-operation with regular Austrian forces. Despite having made peace with the French, the local authorities were unable to suppress a countryside in open revolt between the Upper Rhine and Lake Constance. First Battle of Biberach 2 October 1796 Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire # 70 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 2003 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com |

In the spring of 1796, three French armies received the order from the Directory to launch a combined offensive towards Vienna. The Army of the Sambre and Meuse under General Jean Baptiste Jourdan was to form the northern spearhead, advancing across the Lower Rhine near Düsseldorf, while at the same time, General Jean Victor Moreau was ordered to cross the upper Rhine with his Army of the Rhine and Moselle and advance down the Danube.

In the spring of 1796, three French armies received the order from the Directory to launch a combined offensive towards Vienna. The Army of the Sambre and Meuse under General Jean Baptiste Jourdan was to form the northern spearhead, advancing across the Lower Rhine near Düsseldorf, while at the same time, General Jean Victor Moreau was ordered to cross the upper Rhine with his Army of the Rhine and Moselle and advance down the Danube.

An armistice had been agreed in Germany, which was to last until 31st May, so Jourdan launched his first attack during the following month, but was defeated decisively at Wetzlar. Thus, the young General Bonaparte was able to make good use of the opportunity to outshine his then better-known colleagues. In a daring spring campaign, he first separated the Piedmont-Sardinian army from the Austrians and knocked Sardinia out of the war by the end of April. This defeat forced both the Austrian k. k. Lombardische Armee under FZM Johann Freiherr von Beaulieu to retreat towards Mantua

and the Austrian military command in Vienna to send significant reinforcements under General der Kavallerie (GdK) Dagobert Sigmund Graf von Wurmser from their Army of the Upper Rhine (25 bat, 10 cos light infantry, 18 sqdns and 36 guns) and from the interior of Austria to the Mantua region.

An armistice had been agreed in Germany, which was to last until 31st May, so Jourdan launched his first attack during the following month, but was defeated decisively at Wetzlar. Thus, the young General Bonaparte was able to make good use of the opportunity to outshine his then better-known colleagues. In a daring spring campaign, he first separated the Piedmont-Sardinian army from the Austrians and knocked Sardinia out of the war by the end of April. This defeat forced both the Austrian k. k. Lombardische Armee under FZM Johann Freiherr von Beaulieu to retreat towards Mantua

and the Austrian military command in Vienna to send significant reinforcements under General der Kavallerie (GdK) Dagobert Sigmund Graf von Wurmser from their Army of the Upper Rhine (25 bat, 10 cos light infantry, 18 sqdns and 36 guns) and from the interior of Austria to the Mantua region.

The size of armies had grown considerably in the 1790s and the existing command structure was inadequate. Although keeping with the standard 18th century organisation of a left and right wing, main body and reserve, Moreau had redesignated them as four corps (based on the French word for “body”, a standard term in the late 18th century describing forces detached from the main army), introducing a more formalised corps system to control and lead it effectively before the campaign began:

The size of armies had grown considerably in the 1790s and the existing command structure was inadequate. Although keeping with the standard 18th century organisation of a left and right wing, main body and reserve, Moreau had redesignated them as four corps (based on the French word for “body”, a standard term in the late 18th century describing forces detached from the main army), introducing a more formalised corps system to control and lead it effectively before the campaign began:

Ferino

Ferino

Fighting in Bavaria – Moreau against Latour

Fighting in Bavaria – Moreau against Latour