Battle of Rolica

17 August 1808

The Battle

by Miguel Freire, Portugal

| |

It seems that Delaborde was very aware of his mission: trade space for time. Today it would be called a delaying operation, perhaps the most difficult kind of operation, for one fights with less resources and on demand must perform a timely breaking of contact (or better, non engagement) with the enemy. There is no need for anything more than an experienced Commander and disciplined troops to ensure some success in this kind of operation, all else being mere details. At the dawn of this same day the British-Portuguese Army left Caldas da Rainha and only in Óbidos took combat formation. General Wellesley’s idea was to engage the position by the front and at the same time make a double envelopment intending to attack the flank in case the forces were withdrawing, or to cut the withdraw routes, in case the units would stand too much time in the same position. So, the troops were disposed like this:

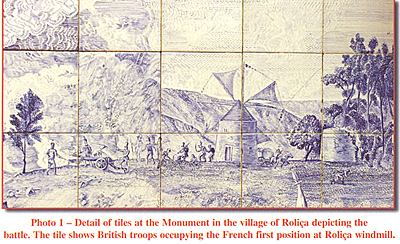

Photo 1 – Detail of tiles at the Monument in the village of Roliça depicting the battle. The tile shows British troops occupying the French first position at Roliça windmill. They withdrew by echelons, first the 70th Regiment and then the 2nd Light Infantry Regiment, the Artillery and the Cavalry establishing a position at Columbeira, about 1600 meters southward from this first position (Photo 1 and 2). The Attack on the Second Position

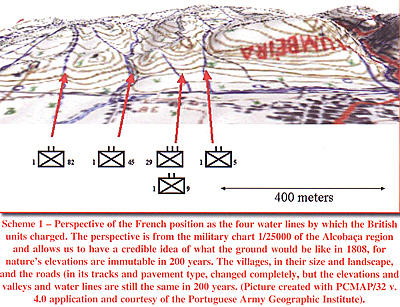

Wellesley kept the same disposition to engage the French second position and did not intended to launch the frontal attack until the flank movements from Trant and Ferguson were also secured.. The attack to the centre would be made by the front Regiments that would use the water lines or passes leading to the top of the Columbeira height line (Scheme 1). All these passes were difficult to access with bushes and sharp rocks that impaired communication amongst regiments. The attack was, therefore, performed with no synchronisation at all, the 29th Regiment accelerated the assault before any other strength was committed. At the end day, from the camp at Vila Verde, General Wellesley, in a letter addressed to the Secretary of State, Viscount Castlereagh, described the assault to the second French position as follows: “The Portuguese infantry were ordered to move up a pass on the right of the whole. The light companies of Major General Hill’s brigade, and the 5th regiment, moved up a pass next on

the right; and the 29th, supported by the 9th regiment, under Brig General Nightingale, a third pass; and the 45th and 82nd regiments, passes on the left.” [13]

At the top of Columbeira, Delaborde had only four Infantry battalions, (Photo 3) since he had assigned three companies from the 70th Regiment to his right side, to where Ferguson was heading. After two hours of fierce fighting, where the British launched three assaults, and in which Delaborde himself was wounded, orders were given to withdraw. The moment had come – Ferguson's troops began to appear from his right flank, The Portuguese forces, on the left flank, did not arrive in time to threaten the French position. Delaborde fell back, keeping two battalions in contact with the enemy while the other two withdraw. He used his Chasseurs à Cheval, in the process loosing their Commander, Major Weiss, to charge over the forward British skirmishers that were pressurising the retreat. The French retreat was made in an orderly and disciplined manner being only disturbed about 1500 ahead to the rearguard where the pass narrowed, at this point there was a slight disorder amongst the French.

As a result from this situation three artillery pieces and some prisoners were “abandoned”. In the words of the British Lieutenant-Colonel Wilkie who saw this retreat, “their (retreats) were made with as much precision as on parade, retiring by files from the right of companies, wheeling up occasionally round their pivot, giving their volley to the light troops in pursuit, and then resuming their former order of march.”

[14]

During the fights Loison would be in Cercal, at about 15 miles East from Roliça, and therefore had no chance to participate. It is interesting to notice that Sir Charles Oman in his work “A history of the Peninsular war” when he describes Roliça, and where at the moment the French Cavalry protects the orderly retreat of its men, he states that “the Portuguese Cavalry refused to engage the other”. General Maximilian Foy states that the Chasseurs à Cheval charged several times without any commitment from the Portuguese Cavalry. [15]

In his report, at the end of the day, Wellesley states that the enemy managed to withdraw in good order owing it firstly to the inexistence of Cavalry, and secondly to the inability to position timely by the water lines a sufficient number of troops and artillery pieces to support the units that made the first assault. [16]

Consequently the version that the Portuguese Cavalry had not committed appears in almost every work. For that reason, it is interesting to mention here one of the few reports from a British Cavalry officer present at Roliça. “We had watched the progress of the battle for some time, without sustaining any injury, ex-cept from a single shell, which, bursting over our column, sent a fragment through the back-bone of a troop-horse, and killed him on the spot – when a cry arose, 'The cavalry to the front!' and we pushed up a sort of a hollowed road towards the top of the ridge before us.

Though driven from their first position, the enemy, it appeared, had rallied, and showing a line both of horse and foot, were preparing to renew the fight. Now, our cavalry were altogether incapable of coping with that of the French; and the fact became abundantly manifest, so as soon as our leading lines gained the brow of the hill – for the slope of a rising ground opposite was covered with them in such numbers, as to render any attempt to charge, on our part, utterly ridiculous.” [17]

Roliça lasted from 9 o’clock in the morning until shortly after 4 o’clock in the afternoon. Delaborde managed to achieve his mission: he had deprived his enemy of time and human resources, preserving his own the best he could.

There are some authors who underline the fact that, though the British were more numerous, the actual forces engaged in real combat were equal. General Wellesley himself supports this argument to emphasise the valour of his troops. I think this is not a matter of emphasis, for if that superiority did not exist, and it was demonstrated in this battle by the double envelopment, not even General Wellesley would dare to attack a position such as that of Columbeira, nor would General Delaborde consider abandoning the battle “so early”. What really mattered in this kind of operation – trade space for time – who has the lack of resources and what are the capabilities of the opponent and not the real number that is to be committed.

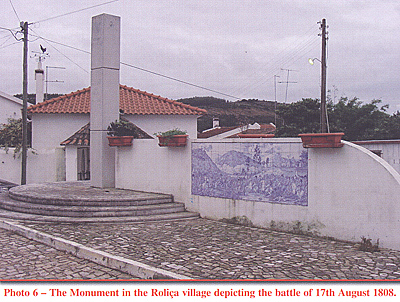

Roliça solved nothing! (Photo 6) Four days later, with the French forces regrouped and the British reinforced, another battle would take place, this time in the Vimeiro region.

No battle analysis, no matter how small, is complete without a slight reference to the Commanders of the forces in combat.

General Delaborde (1764 – 1833)

He enlisted himself at the age of 19 as a soldier in the Régiment de Condé, but the Revolution allowed him a fast climb and in 1793 he was Division General. In the first French Invasion of Portugal he leaded a Division. He returned to the Peninsula with Soult fighting in Corunna and in Oporto. General Foy in his work “Histoire de la Guerre de la Péninsule sous Napoléon” published in Paris in 1827, he wrote about Delaborde complementing his sang-froid and energy. He described him as being an “old warrior respected by his men and that rapidly inspired them due to his vigour and confidence.”

[18]

Wellesley himself recognised the ability, swiftness and courage in the way that the French defended themselves.

[19]

In 1808 he was invested Count. Became a commander of an Imperial Guard division in the Russian campaign. In 1815 he joined Napoleon but after Waterloo he retired.

General Wellesley (1769 – 1852)

We refer obviously to the Duke of Wellington. To Talk about Wellesley is to talk about the Peninsular War and I intend to cover him further in my next article in issue 70 on the battle of Vimeiro.

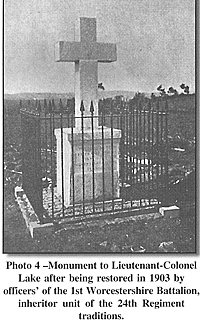

Right: Photo 5: Monument to Lieutenant-Colonel Lake in November 2002. After almost a century, and though well sign-posted, it may not need further restoration but it could at least do with being kept tidy!

In Volume X of “Organic and Political History of the Portuguese Army” written by Colonel Christovam Ayres de Magalhães Sepulveda and published in 1913, there is an interesting chapter about the memorial in honour of Lieutenant-Colonel Lake, Commander of the 29th Regiment.

The monument still exists on top of Columbeira. It was on that spot that Lieutenant-Colonel Lake was buried on the 17th of August of 1808, having been killed leading his Regiment in a charge

against the French along one of the water lines that led to the Columbeira.

In April of 1903 Victoriano José César wrote to Christovam Ayres that “today this unique monument is about to disappear through neglect and abandonment, it should be a duty of ours to preserve this homage to the bravery of that one, who fighting for Portugal, here shed his blood and gave his life.” [20]

Colonel Christovam Ayres was not insensitive to the letter and studied the possibility of restoring the monument at the Portuguese Government's expense or by the officers of the 29th Regiment. The monument was restored at the expense of the officers during August 1903. It is a curious fact that Ayres found, within the resident British community in Portugal, a descendant of a soldier who fought at Roliça and Vimeiro and that he had a son, who was then a Lieutenant in the 1st Worcestershire Battalion, which had been formed from the 29th and inherited the 29th Regimental traditions. It was via this Lieutenant, Alfred F. Custance, that contact was established with officers of the Battalion so that the monument could be restored at their expense. (Photos 4 and 5)

Though properly signposted, the monument still needs further restoration!

Author would like to thank the Army Geographic Institute for the loan of the PCMAP/32 version 4.0 application in order to make the perspectives used in the schemes 1 and 2.

[1] On the 25th of June Napoleon met with Alexander of Russia for talks. On the 9th of July the peace treaty was signed with Russia and on the 12th of July with Prussia. Russia, out of Napoleon’s generosity, managed to achieve a little more than its defeated status at Friedland would foresee. On the other hand, Prussia was humiliated loosing many of its possessions.

Battle of Rolica 17 August 1808

|

Photo 6 – The Monument in the Roliça village depicting the battle of 17th August 1808. Another detail of the tile on the Roliça Monument. The tile shows the strength of the 2nd French Position. On it, we can see the silhouettes of French soldiers on the top of Columbeira.

Photo 6 – The Monument in the Roliça village depicting the battle of 17th August 1808. Another detail of the tile on the Roliça Monument. The tile shows the strength of the 2nd French Position. On it, we can see the silhouettes of French soldiers on the top of Columbeira.

The French occupied the Roliça windmill position and Delaborde gave orders to withdraw as Fane's skirmishers began exchanging fire with his, while Trant and Ferguson were coming from the flanks.

The French occupied the Roliça windmill position and Delaborde gave orders to withdraw as Fane's skirmishers began exchanging fire with his, while Trant and Ferguson were coming from the flanks.

Scheme 1 – Perspective of the French position as the four water lines by which the British units charged. The perspective is from the military chart 1/25000 of the Alcobaça region

and allows us to have a credible idea of what the ground would be like in 1808, for nature’s elevations are immutable in 200 years. The villages, in their size and landscape, and the roads (in its tracks and pavement type, changed completely, but the elevations and valleys and water lines are still the same in 200 years. (Picture created with PCMAP/32 v. 4.0 application and courtesy of the Portuguese Army Geographic Institute).

Scheme 1 – Perspective of the French position as the four water lines by which the British units charged. The perspective is from the military chart 1/25000 of the Alcobaça region

and allows us to have a credible idea of what the ground would be like in 1808, for nature’s elevations are immutable in 200 years. The villages, in their size and landscape, and the roads (in its tracks and pavement type, changed completely, but the elevations and valleys and water lines are still the same in 200 years. (Picture created with PCMAP/32 v. 4.0 application and courtesy of the Portuguese Army Geographic Institute).

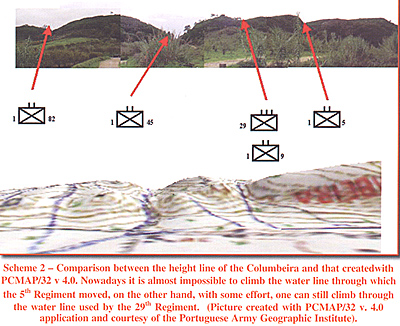

Scheme 2 – Comparison between the height line of the Columbeira and that created with PCMAP/32 v 4.0. Nowadays it is almost impossible to climb the water line through which

the 5 th Regiment moved, on the other hand, with some effort, one can still climb through the water line used by the 29 th Regiment. (Picture created with PCMAP/32 v. 4.0 application and courtesy of the Portuguese Army Geographic Institute).

Scheme 2 – Comparison between the height line of the Columbeira and that created with PCMAP/32 v 4.0. Nowadays it is almost impossible to climb the water line through which

the 5 th Regiment moved, on the other hand, with some effort, one can still climb through the water line used by the 29 th Regiment. (Picture created with PCMAP/32 v. 4.0 application and courtesy of the Portuguese Army Geographic Institute).

Left: Photo 4: Monument to Lieutenant-Colonel Lake after being restored in 1903 by officers’ of the 1st Worcestershire Battalion, inheritor unit of the 24th Regiment traditions.

Left: Photo 4: Monument to Lieutenant-Colonel Lake after being restored in 1903 by officers’ of the 1st Worcestershire Battalion, inheritor unit of the 24th Regiment traditions.