Battle of Rolica

17 August 1808

Opening Maneuvers

by Miguel Freire, Portugal

| |

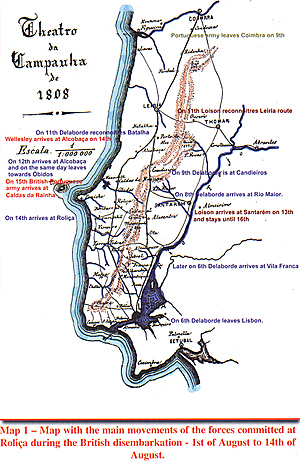

Map 1 – Map with the main movements of the forces committed at Roliça during the British disembarkation - 1st of August to 14th of August.

With the Tilsit Treaty [1] Europe achieved a frail peace but that was enough for Napoleon to advance beyond the Pyrenees. Napoleon dominated the whole Europe; only England was safe, though while France ruled over the land, England was still ruling over the seas. As it was not possible to Napoleon to engage England, he decided to enforce a trade blockade, that is, the so-called Continental System. The idea was to suffocate England economically and commercially. This system forbade all maritime commercial transactions between England and the Continent and all British goods were to be confiscated in all territories occupied by the French army, or its allies. The whole of Europe obeyed this system. Only Portugal, resisted maintaining a two-faced policy, maybe due to the fact that Portugal was faced with the twin threats of either a French invasion, if Napoleon’s orders of closing all ports to the British vessels were not carried out, or a take over of its colonies by England, who ruled the seas.

Faced with Portugal’s indefinable stance to the Continental System, on the 27th of October 1807 Napoleon brokered the secret Treaty of Fontainebleau with D. Manuel Godoy, [2] by which the Spanish Court compromise to help the French conquer Portugal that would afterwards be divided into three small kingdoms. Some ten days prior to the signature of the treaty' General Junot’s army was already in Spain, with the Spanish Army Corps of General Solano to the South and two divisions to the North, prepared to enter Portugal fulfilling the division of it in the preset three small kingdoms.

The French and Spanish armies entered Portugal without encountering any resistance whatsoever. In 1807 “the (Portuguese) line Army, badly paid, undisciplined, with no arms, with no instruction or command, demoralized (…) was a horde of invalids and politic-makers with whom one could not rely on to do war”. [3]

Although in 1806 the Army had undergone a reorganisation in order to update its structure, being organised into divisions and brigades and even a new Uniform Plan. The truth was that the line Army with its 24 Infantry Regiments, 12 Cavalry Regiments and 4 Artillery Regiments could not gather more than 10,000 to 12,000 men. With so few troops to oppose the invader there was no other option than not to resist, and to safeguard Portugal’s sovereignty the Court and the Government withdrew to Brazil. As the French established sovereignty in Portuguese territory, despite being allies, the relationship between France and Spain deteriorated to the point they turned on each other.

The most noteworthy event was the insurrection on the “2nd of May” in Madrid; thirty French soldiers and hundreds of Spaniards were killed on the streets. The next day, on orders of Marshal Murat, about one hundred Spaniards were executed. France was from now on considered the invader in both peninsular countries.

Upon hearing of the insurgencies in Spain, England decided to help Portugal and Spain economically, financially and militarily by sending an expeditionary force to the Iberian Peninsula. Spain accepted only material help. Portugal, however, accepted all help and integrated the army with the British forces, eventually achieving the status of Brothers in Arms.

By the summer of 1808, France and England knew what was at stake in the Iberian Peninsula and what they should do. Using current terms of military doctrine [4] we can say that to the British the operation End-state [5] would be to support Portugal and Spain in pushing out the invading troops of France and assure a final and total withdraw of that forces of the Iberian Peninsula. The Centre of Gravity [6] was the supremacy of the British Navy on the seas. Though war’s nature only allowed a victory through military operations successfully carried out on land. The contribution of the Royal

Navy was vital to maintain unrestricted communication and supply lines with England, or even to facilitate an evacuation of British forces as happened later at Corunna in 1809.

The Decisive Point [7] was Lisbon’s recapture and liberation. When on 24th July Wellesley disembarked in Oporto for talks with the Government, the Government thought that this was the right move as disembarking as close as possible to Lisbon meant that Junot would not have time to regroup his troops.

[8]

For Napoleon's, the End-state of invasion was the blockade of the Tagus, denying access to the Royal Navy and the end of all trade relations between the British and the Portuguese ports (although the colonies’ ports were still inaccessible). As Centre of Gravity the French were interested in maintain the population on their side. The French knew they had to have the support of the Portuguese people (or at least not have their hostility), in order to carry out their operations, to maintain their lines of communication, of supply and to gather information. Furthermore, this feeling is shown in the words of Junot to the Lisbon people on his arrival “… I come to save your port and your Prince from England’s bad influence (…) Lisbon people worry not and stay in your homes; have no fear nor of my army

nor of me; our enemies and the wicked ones are the only that should fear us.” [9]

On the 16th of August when Junot had to leave Lisbon heading with the Army core to the North, he spoke to the Lisbon people like this. “I leave only for three or four days. I am visiting my

Army and if necessary give fight to the British, and whatever the result, I shall return to you. To govern Lisbon I leave a General that because of his consideration and strength of character I know to have deserved the respect of the Portuguese in Cascaes and Oeiras [10] (…). You have been so far quiet; and that is how you should continue: Stain you not with any hideous crime, at any moment our luck in

arms will decide, with no risk whatsoever to you, the power that shall rule you.” [11]

Knowing in advance that by spreading their forces could be fatal to them, the Decisive Point of the French was to maintain its forces ready to, at any time, regroup and engage the invading army that could disembark at the coast.

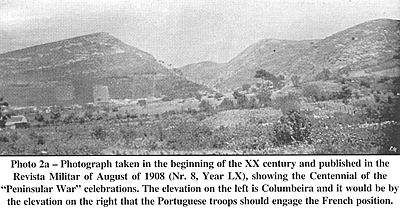

Photo 2a – Photograph taken in the beginning of the XX century and published in the Revista Militar of August of 1908 (Nr. 8, Year LX), showing the Centennial of the “Peninsular War” celebrations. The elevation on the left is Columbeira and it would be by the elevation on the right that the Portuguese troops should engage the French position.

This operation took almost five days until all the units were ashore. When Junot was informed that the British were disembarking he gave orders to General Delaborde to go meet the British with one Division and ordered General Loison, who was heading to Badajoz, to march to Abrantes. Meanwhile elements of the Portuguese Army led by the General Bernardim Freire were heading south to Leiria to join Wellesley’s Army. The set of main movements of these forces can be seen in Map 1 and this will be concluded, at a first moment, on the 17th of August with the Roliça fight. The Order of Battle of the committed units are the ones shown in the Chart 1 for the British, Chart 2 for the Portuguese and Chart 3 for the French.

On the 14th of August, Delaborde occupied the region of Roliça disposing his troops as follows:

Loison was striving to join his forces with Delaborde, but after a reconnaissance of the area made from the Leiria route, on the 11th, he saw that the British-Portuguese Army was already in the town so he withdrew to Torres Novas and then headed to Santarém. From the day he was ordered to head to Abrantes, Loison had force-marched his troops. In Santarém, Loison had to give in and rest his men, he

staying in the town until the 16th of August. This rest period would hinder Loison joining Delaborde in time to jointly engage the British.

The fusion of the Portuguese army forces with the British was not a simple and objective process. General Bernardim Freire, to whom had been given command of what was left of the Portuguese Army, was reluctant to leave behind the Cavalry, the Light Infantry and 1000 men of the Line and only by pressure of Wellesley did he concede.

On the 15th of August the Advanced Guard of the British Army established contact with the French Advanced Outposts in Óbidos and Arrifos. The French soon abandoned Arrifos, but in Óbidos the British paid for their daring. After pushing out the French from this position they pursued until the French finding a suitable position to make a stand, repulsed the four British companies that, without any

backup whatsoever, had engaged in the pursuit. About 70 British were killed and others wounded in this fight. By the end of the day, the British frontline was in Óbidos and the Army’s main body was in Caldas da Rainha.

On 16th August the British performed some reconnaissance tasks while the French prepared their position at Roliça.

Battle of Rolica 17 August 1808

|

Napoleon had defeated Austria and Russia at Ulm and Austerlitz in 1805, and beaten Prussia at Jena in 1806 and overcame Russia, once more, at Friedland in 1807.

Napoleon had defeated Austria and Russia at Ulm and Austerlitz in 1805, and beaten Prussia at Jena in 1806 and overcame Russia, once more, at Friedland in 1807.

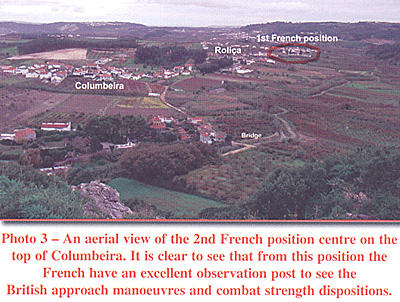

Photo 3 – An aerial view of the 2nd French position centre on the top of Columbeira. It is clear to see that from this position the French have an excellent observation post to see the

British approach manoeuvres and combat strength dispositions.

Photo 3 – An aerial view of the 2nd French position centre on the top of Columbeira. It is clear to see that from this position the French have an excellent observation post to see the

British approach manoeuvres and combat strength dispositions.

The British fleet came to the Mondego mouth on the 30th of July and began disembarking on the Lavos beach immediately the day after.

The British fleet came to the Mondego mouth on the 30th of July and began disembarking on the Lavos beach immediately the day after.