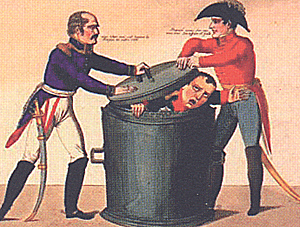

A Belle Alliance

The Battle About Books

About the Battle

Main Controversy

by Gary Cousins, Germany

| |

However, the main controversy is undoubtedly about the events in the final phase of the battle of Waterloo on the 18th June -– specifically the operations and (inevitably) the contributions of the armies of Wellington and the Prussians. Here the difference between the quantitative and the qualitative is arguably more significant. "History" says that Wellington’s troops defeated the final French attack on his line, a struggle involving at least 33,000 troops [9], and then made a (triumphant, victorious, glorious, brilliant, etc...) general advance, led by 3 (largely British) brigades, rolling up the centre of the French army and crushing its reserves

"…in such a manner as to render the incipient panic which it [the repulse of the imperial guard] had created, general and uncontrollable…" ("History", p.356). At the time of this initially limited follow-up by Wellington’s line , the Prussians’ disposition was "…that the advanced portion of Zieten’s corps had joined the left of the allied line, that part of Pirch’s

corps (including his reserve cavalry,) had joined Bülow; and that the latter was on the advance -- his right to attack Lobau, and his left to make a third assault on Plancenoit -- the French opposed to them evincing, at all points, every indication of making a firm and determined stand" ("History", p.354).

On the extreme left of Wellington’s line, Ziethen’s Prussian advanced cavalry and infantry joined just before the general advance at 8pm. In an unfortunate incident, some of the Prussian infantry exchanged fire with the Nassauers

of the 2 nd Brigade of the 2 nd Netherlands Infantry Division. Vivian and Vandeleur

had already moved their cavalry brigades towards the centre of the line.

Mr. Hofschröer’s statement in [2] that Vivian "had only been able to do so because the Prussians had relieved him", and that he did so on Wellington’s orders, stretches the "facts" related in "History", according to which Vivian did not wait for Ziethen’s troops to relieve him, but having become impatient of waiting for the Prussians to

join the line (despite them having been sent several messages urging haste), he moved off on his own initiative, without waiting for orders, followed more reluctantly by Vandeleur ("History", p.354). Vivian later called the Prussian advance "tardy" ("Letters" p. 152).

"History" then describes the point at which Wellington decided to make the

advance general: "Wellington, perceiving the confusion in which the columns of the

French imperial guard fell back after the decided failure of their attack -– a

confusion which was evidently extending itself with wonderful rapidity to a vast

portion of the troops in their vicinity who witnessed their discomfiture; remarking

also the beautiful advance of Vivian’s hussar-brigade against the French reserves

posted close to La Belle Alliance, and in the very heart of Napoleon’s position; as

well as the steady and triumphant march of Adam’s brigade, which, driving a host of

fugitives before it, had now closely approached the nearest rise of the French

position contiguous to the Charleroi road; finally, observing that Bülow’s movement

upon Planchenoit had begun to take effect, perceiving the fire of his cannon, and

being also aware that part of a Prussian corps had joined his own left by Ohain,

he ordered a general advance of the whole of his line of infantry, supported by the

cavalry and artillery" ("History", p.361).

This passage, in text and structure, so closely resembles a passage from Wellington’s Despatch [10] that it is clear that it is based upon the Despatch, and since Siborne Sr. makes no comment about the accuracy of the Despatch, adverse or

otherwise, it must be assumed that either he saw nothing wrong in its contents -- i.e.

that after all his "very careful research", he also regarded the Despatch as "high

authority" -- or he was himself an apologist for any of its shortcomings. Yet this is the

very same passage from the Despatch which Mr. Hofschröer quotes in "Peer Pressure!" to suggest that it shows that Wellington deliberately played down the role of the Prussians up until that point of the battle.

Mr. Hofschröer chooses to interpret this passage as a description of a sequence of events: first the French cavalry attacks, then the final French attack and defeat, then the effective Prussian intervention.

Thus Wellington, it is implied, says that the Prussian intervention had begun to take

effect only after the last attack was defeated, so as to take the credit for the victory through his general advance. It is perhaps not surprising that Mr. Hofschröer has chosen the interpretation which most sharpens the axe he is grinding.

It is equally possible that Wellington was describing, in no particular order, the thought process behind the decision - the several events or conditions which, now all occurring or culminating, he took into account when he arrived at the judgement that it was safe to order a general advance.

Only after the repulse of the final French attack, and having been joined on his left

wing by the Prussians, and seeing their advance upon the French right wing, did

he have confidence that a general advance was possible. It does not imply that

Wellington had seen no Prussian intervention at Plancenoit or on his left

wing before the end of the battle, even though it is clear that Wellington has

omitted to state in the Despatch -- either at that particular point or to be more

chronologically accurate earlier - that the first Prussian intervention occurred earlier

than his defeat of the final French attack and the general advance.

The Prussians had already pushed back Lobau’s troops towards Plancenoit, had made 2 assaults

upon that village, and had been driven out again by French reinforcements, first from the Young Guard and then from the Old Guard. But "History" says that Wellington was generally aware of the Prussian intervention long before, but could not judge how supportive it would be, or see the detail: "Although the Duke was aware that Bülow’s corps was in active operation against the extreme right of the French army, the ground upon which that operation was mainly carried on was too remote from his own immediate sphere of action to admit of his calculating upon

support from it, beyond that of a diversion of the enemy’s forces; and it was only from the high ground on which the extreme left of the Anglo-allied line rested, that a general view could be obtained of the Prussian movements.

As regards, however, the village of Plancenoit itself…it was scarcely possible to

distinguish which was the successful party in that quarter. Napoleon might (as he

really did) present an efficient check to the Prussian attack, and at the same time retain

sufficient force wherewith he might make another vigorous assault upon the Anglo-allied

army" ("History", p.326).

Not Sure

One cannot be sure whether Wellington was using the phrase "to take effect" in the Despatch to mean "to happen", or "to become effective", when he says that when he ordered the general advance "…the march of General Bülow’s corps, by Frischermont, upon Plancenoit and La Belle Alliance, had begun to take effect…" ("Despatch"). However, whichever one chooses, the fact of Prussian intervention was not in itself sufficient for him to order a general advance: hitherto, it had not been, as far as he was concerned, sufficiently effective and directly supportive of his line. Siborne Sr.’s "History" later says approvingly that Wellington’s "…consummate and unerring judgement had caused him to defer the [general] advance until the attack could be undertaken with every probability of success" ("History", p.361). This is not

inconsistent with Wellington’s "Memorandum" of October 1836, ("Supplementary Dispatches…" vol. X, 513: quoted in [2]): "…I was informed that the smoke of the fire of cannon was seen occasionally from our line behind Hougoumont at a distance, in front of our left, about an hour before the British army advanced to the attack of the enemy's line...That attack was ordered possibly at about half-past seven, when I saw the confusion in their position upon the repulse of the last attack of their infantry...". (Taking no particular heed of the timings -- elsewhere they differ from those generally accepted).

Having said that, the Despatch could perhaps be accused of being inaccurate, sloppy, idiosyncratic, imprecise, oversimplified, understated, misleading, etc., and therefore not up to the rigorous and pedantic standards of the historian, but it is open to question whether it is deliberately false -- i.e. a lie. In general the Despatch was not meant to be a detailed

and accurate description of the operations or the relative contributions of the two allied armies -- under the circumstances in which it was written it could not be, and for many reasons which Mr. Hofschröer does not consider. (For a discussion of some, but not all, of these considerations, see [11]). It is also self-obsessed -– describing things mainly from Wellington’s viewpoint -- again perhaps that is understandable given that Wellington’s perspective may have been coloured by the fact that his army had just

spent over nine hours under fire, enduring several attacks on the main battlefield, anxiously and impatiently awaiting the promised Prussian assistance -- even if he had been kept up-to-date on Prussian movements towards the battlefield, or knew of the details of the early stages of the Prussian involvement against the French right wing, or knew of the battle at Wavre.

Later in the Despatch Wellington states, perhaps realising that he has earlier understated the Prussian role: "I should not do justice to my own feelings, or to Marshal Blücher and the Prussian army, if I did not attribute the successful result of this arduous day to the cordial and timely assistance I received from them. The operation of General Bülow upon the enemy's flank was a most decisive one; and, even if I had not found myself in a situation to make the attack which produced the final result, it would have forced the enemy to retire if his attacks should have failed, and would have prevented him from taking advantage of them if they should

unfortunately have succeeded…."

If one sees shortcomings in Wellington’s Despatch, then what should one make of the Blücher / Gneisenau Report, which is idiosyncratic in its own way, and also totally at variance with

Siborne Sr.’s version of events? It omits the entire final French attack on Wellington’s

line, (as stated a struggle involving at least 33,000 men) - Blücher being, as "History"

points out, wholly unaware of the extent to which Wellington had attacked the centre of the French army and pushed his advanced brigades to the very rear of the troops which the Prussians had been opposing. The final attack of the French upon Wellington’s line is mentioned almost only in passing by von Plotho, ("Verbund", p.62), perhaps following that Report.

The Blücher / Gneisenau Report also appears to attribute the French rout to the attack by Ziethen’s troops from Wellington’s left, and von Plotho also follows this line, saying that

Ziethen’s advance troops joined Wellington’s left, linking the two allied armies, and began their attack, which "…decided the battle" ("Verbund", p. 68) since the French found themselves assailed on three sides and began a general retreat, which turned into a rout. Vivian, quoted by Mr. Hofschröer in [2] in support of Siborne Sr., disagreed: he argues for the decisive influence of the advance of two brigades of Wellington’s cavalry -- including his own - in causing the French rout ("History", esp. pp. 157 et seq.) -- contradicting Prussian claims for Ziethen: and in general he is by no means as unequivocally supportive of Mr. Hofschröer’s case as suggested - see both "History" and "Letters"– but then he too went on to become a politician…

"History" says: "The French historians invariably attribute the final deroute of their

army to the charges made by the British light cavalry launched against it immediately after the attack by the imperial guard" ("History", footnote, p.392). It seems that early accounts from both sides were inaccurate and partial.

Wellington predicted: "I shall certainly be involved in a controversy with nations as well as individuals; which will not be an agreeable pastime in my old age!" (WP 2/34/135-6, Wellington to Colonel Gurwood, 30th July 1835: quoted in [12],

p.5): and one reason was the controversy over Siborne Sr.’s model of the battle of Waterloo, the subject of Mr. Hofschröer’s article "Peer Pressure!", which tries to show that Wellington was a ruthless man, prepared to distort or falsify the truth in pursuit of his personal and political ambitions, who personally orchestrated a smear campaign of which the "too pro-Prussian" Siborne Sr.’s health and wealth was the victim.

Siborne Sr. says in "History" that the original version of his model showed the Prussian troops between the extreme allied left and Plancenoit in too forward a position, giving "…the appearance of a much greater pressure upon the French right flank than could have occurred at the moment represented on the model" ("History", p.398).

The cause is attributed to errors in Prussian accounts, in which the defeat of the final French attack and the general advance occur simultaneously, when according to Siborne Sr. there was an interval of twelve minutes between the two events. His original model therefore showed Wellington’s troops as they stood when the final French attack was defeated, but the Prussians in the more advanced position they only occupied some quarter of an hour later: it did not compare like with like. If that was all that caused the controversy, then a correction of the model to bring the relative dispositions of the troops of Wellington and the Prussians into line was all that was needed, and was made. But it was no doubt about more than that.

A Belle Alliance The Battle About Books About the Battle

|