Peer Pressure

Wellington, Siborne, and the Waterloo

Model Exhibited 1838

by Peter Hofschroer, Austria

| |

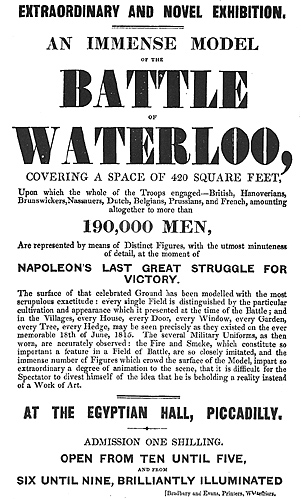

Flyer of the 1838 Exhibition of the Large Model. Siborne did not represent all the soldiers on the battlefield on a 1:1 scale, but used a proportion of around 1:2. The figures, about 10 mm high, are so detailed they even have moving parts! In 1841, there was a change of government, when the Tories under

Peel regained office. In May, Siborne petitioned parliament to purchase the

Model for the nation. He also wrote to Hardinge, now the new Secretary of

War in Peel’s administration, asking for his support. Hardinge declined his

request with disdain. Others, including Murray, were more amenable, but could

do little to help Siborne. [14]

Wanting to recover his costs, in a letter of 16 September to Hardinge, Siborne wrote,

‘I am well aware that in the opinion of some of our highest military

authorities, the Prussian troops occupy too prominent a position upon the

Model, an opinion to which I should be sorry to be so presumptuous as to

oppose my own impressions, which may be very possibly erroneous, and

the moment the work ceases to be my property and I am no longer obligated

to adhere to those impressions, I shall be most willing & able to make any

alterations that may be suggested in this or in any other respect’. [15]

In other words: “Buy the Model and I will change it”, but that was not to be. As Vivian pointed out, ‘then

comes the Money, then comes the difficulty of disposing of the Model & lastly there comes the D of Wellington,

for without him they will not one of them stir one inch’. [16]

As Siborne had embarrassed Wellington by refusing to change his Model before it was

exhibited, the new Tory government would not help him out of his predicament and purchase it.

With the Model completed, Siborne returned to writing his History of the Waterloo Campaign. From 1842 onwards,

he approached various people to enquire if they would be interested in subscribing to his book. It became

known in certain circles that the man whose Model had so upset Wellington was to publish a History of the Campaign.

On 23 September 1842, the Francis Egerton, an authority on military history and at one time Secretary of

War, wrote to Charles Arbuthnot. Both were close associates and advisors of the Duke.

Egerton commented, ‘I see also that Siborne, the officer who made that curious model of the

battle, is about to publish a detailed account. Under these circumstances I

think it probable that a good opportunity may present itself of such further use of

the Duke’s [Waterloo] mem m . [of September 1842] as may be required. When I

first saw Siborne’s model I suspected that he had been humbugged by the Prussians,

& I remember mentioning my opinion to Fitzroy Somerset’. [17]

In this Memorandum that Wellington expressly stated should not be published, he wrote,

‘The perusal of the account of this battle will show where the historian

[Siborne] collected the facts which he narrates. But some of the most important

facts of the battle are omitted; because the only authorities from

whom information was never required were the Commander-in-Chief himself,

and the Officers of the general Staff, and those acting under his immediate

orders in the Field.’ [18]

Using this Memorandum as a reference, Egerton wrote a review of Siborne’s History that was published

in the prestigious “Quarterly Review”.

He commented, ‘…The work of Captain Siborne demands a portion of our space … his

work is defective in one important particular. It seems to us, as far as the

British operations are concerned, drawn from every source except from

the commander-in-chief and the few officers attached at the time to headquarters

who really knew or could know anything of value about the great features of the business. This imperfection

is in our opinion very observable in one or two passages, which we shall

shortly have occasion to quote.’ [19]

As we saw earlier, Siborne had certainly consulted the Commander-in-Chief

and Wellington was aware of that. There are a number of further

instances of the Duke’s denigration of Siborne. One of these is related in

“Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine”.

Here, Wellington was asked by one of a group of judges, politicians and

dignitaries he was entertaining what he thought of Siborne’s Model: ‘That is a

question I have often been asked, to which I don’t want to give an answer,

because I don’t want to injure the man. But if you want to know my

opinion, it’s all farce, fudge!’ [20]

If he really had not wanted to injure Siborne, then Wellington would not

have made such a comment in front of a gathering of prominent people. The

Duke was certainly not going support to the man the Prussians had

‘humbugged’. In fact, Siborne had to die before his Model was purchased.

Two years afterwards, in 1851, it was placed on display in the Large Gallery

in the United Services Institution, London, where it remained for more than a century.

Records from 1834 to 1845 show that Siborne was in regular correspondence

with FitzRoy Somerset and that Wellington was aware of Siborne’s wish to obtain information

from him and officers on his staff at Waterloo. Records from September

and October 1836 demonstrate that Wellington commented on Siborne’s

approaches for information. Siborne had contacted the Commander-in-Chief,

so Wellington knew his denial of this was false. The Duke subjected Siborne

to a smear campaign for having the nerve to establish and publish historical

fact. Egerton noted that ‘... I wrote a letter, dated 18 May 1845, to Arbuthnot,

in which I deprecated the Duke’s severity towards Siborne.' [21]

This episode demonstrates that the image presented by certain historians of

the immaculate omniscience of Arthur, Duke of Wellington, is questionable.

His treatment of Siborne shows Wellington to have been a ruthless politician,

who considered his public image paramount. This episode also shows that the Duke went to considerable

efforts in the years following Waterloo to attempt to ensure the role of his Prussian allies in the victory at this

battle was not given its due credit. Historical truth was a casualty in this process and to this day, there are those

who wish it would remain so.

[1] The exact date of Siborne’s enquiry is not known as he did not keep a file copy, but the replies in

British Library London [hereafter BL], Siborne Papers, Add MS 34,703, fol. 192 are dated 29

October to 3 November 1834.

Peer Pressure Wellington, Siborne, and the Waterloo

|

In 1838, the Model was exhibited at the Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly and was visited by 100,000 people, each of whom paid one shilling to see it, a total of £5,000. Siborne was hoping that the revenues from this exhibition would clear his outstanding debt of £3,000. However, it seems that the manager appointed to run the exhibition might have cheated Siborne of his share of the income and did not give him a penny. Siborne would have little chance of clearing his debts on the pay of an army lieutenant.

In 1838, the Model was exhibited at the Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly and was visited by 100,000 people, each of whom paid one shilling to see it, a total of £5,000. Siborne was hoping that the revenues from this exhibition would clear his outstanding debt of £3,000. However, it seems that the manager appointed to run the exhibition might have cheated Siborne of his share of the income and did not give him a penny. Siborne would have little chance of clearing his debts on the pay of an army lieutenant.