Peer Pressure

Wellington, Siborne, and the Waterloo

Introduction

by Peter Hofschroer, Austria

| |

Left: Captain William Siborne (1797-1849). This is the only known portrait of Siborne. It is currently in the possession of the family. My thanks go to Brian Siborne for his kind permission to reproduce this and to Bruce Allen Hendrix MPA, F.Ph. of Clearbrook Photographic Arts Inc. for supplying this photograph of the original. The portrait was painted by Samuel Lover, R.H.A. about 1833. Captain William Siborne is best known for his classic

History of the Waterloo Campaign and his Model of the Battle of Waterloo. First exhibited in 1838, it is now on display at the National Army Museum in London.

As we shall see, Siborne’s Model caused considerable controversy even before it was completed, with the first Duke of Wellington orchestrating a campaign to discredit him. Siborne, an honest historian, had done his research thoroughly. His version of events conflicted with Wellington’s, who was anxious to project a certain public image. Siborne’s Model, and later his History, showed the true role of the Prussian army at Waterloo, whereas Wellington was keen to present himself as the victor, minimising the Prussian role.

In 1830, the British army decided to honour Wellington by making a model of the Battle of Waterloo. Viscount Rowland Hill, then Commander-in-Chief, commissioned Siborne to design and construct this model that was to be funded from the public purse. Siborne was Assistant Military Secretary to the Commander-in-Chief Ireland, then Sir John Byng. Siborne spent several months in residence at the farmhouse of La Haye Sainte, a central feature of the battle,

making a thorough survey of the field. Sir Henry Hardinge, Waterloo veteran and a close associate of Wellington, assured Siborne that his costs would be met from public funds. At first, they were.

In 1833, after a change of government, the Whigs under Earl Grey gave Siborne the option of having the expenses incurred to date paid and terminating the project, or continuing it at this own cost. Siborne continued, being obliged to finish what he had started as he had already contracted out much of the work to tradesmen. He was expecting Hardinge to keep his word and a future Tory government to make good his outlay. As it happened, the Tories only got back into power in 1841.

When constructing the Model, Siborne decided to show the crisis of the battle, positioning the troops where they would have been about 7 p.m. To attain the greatest possible accuracy, Siborne went to the trouble of contacting many survivors of the battle, particularly officers in the British and German forces in Wellington’s army.

He also corresponded with Major von Gerwien of the Prussian General Staff.

Siborne did not accept the information given him uncritically and a long

discussion often took place before agreement on certain points was reached.

Siborne also contacted the Duke of Wellington. He did not write to Wellington directly, but approached the Duke through others, particularly FitzRoy Somerset, the Military Secretary.

This correspondence continued for twelve years from 1834 to 1845.

Starting in 1834, Siborne sent a circular letter to various participants of

the campaign. He enclosed a copy of his Plan of the battlefield, asking them

to state the formation of their unit and to mark the position of the attacking

Imperial Guard. Siborne collated the answers and by cross-referencing them

with each other, hoped to establish the likely positions and movements of the

forces involved in the Crisis.

Peer Pressure Wellington, Siborne, and the Waterloo

|

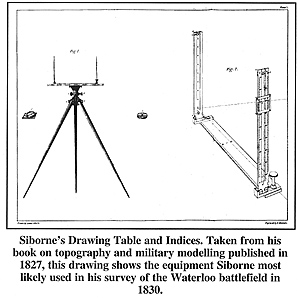

Siborne’s Drawing Table and Indices. Taken from his book on topography and military modelling published in 1827, this drawing shows the equipment Siborne most likely used in his survey of the Waterloo battlefield in 1830.

Siborne’s Drawing Table and Indices. Taken from his book on topography and military modelling published in 1827, this drawing shows the equipment Siborne most likely used in his survey of the Waterloo battlefield in 1830.