Jena Auerstadt

A Day of Lost Opportunities

Battle of Jena

by Patrick E. Wilson

| |

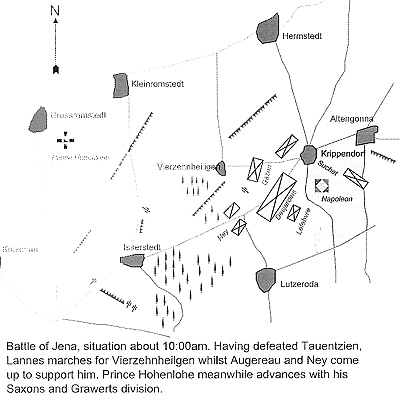

Which is why the French attacked so early, though General Tauentzien’s forward probes may have contributed to the decision. Still because of their compact mass, at least early on, the French lost heavily as they pushed forward. Despite the fact that neither side could see each other

and were firing blind into the fog. Eventually, as the French pushed forward the fighting centred on the two villages of Lutzeroda and Closewitz.

General Tauentzien had his troops well deployed with fusilier battalions and Jäger companies to the fore in the villages and woods around them. His main body was behind the villages ready to support and though his command comprised both Saxon and Prussian troops, it fought well.

It was about 8.00am when they were finally forced from the villages of Closewitz and Lutzeroda, Tauentzien having bought Prince Hohenlohe two hours by his fighting skills.

General Tauentzien had been keeping Prince Hohenlohe informed of developments on his front that morning and the urgency of his messages grew! Prince Hohenlohe himself seemed to be convinced that a major battle would not be fought that day and despite the growing noise of firing on his left, was annoyed when he discovered that General Grawert had already assembled his division in anticipation. Indeed, some elements were already marching toward the sound of the fighting. Fortunately Grawert himself soon arrived to convince Prince Hohenlohe

of the need to assist General Tauentzien. Sending Grawert’s cavalry ahead to aid General Tauentzien’s retreat from Lutzeroda and Closewitz, Prince Hohenlohe helped General Grawert in the deployment of that General’s infantry prior to its advance.

Meanwhile there had been another significant fight; Marechal Soult’s leading division under General St. Hilaire had been engaged against General Holtzendorf’s detachment on General Tauentzien’s right around Lehesten. General Holtzendorf had a grenadier and a cavalry brigade and

was endeavouring to rejoin the main body of Prince Hohenlohe’s force by the direct approach, straight through the enemy that threatened to engulf him! It was a brave but foolhardy move.

Advancing with the regularity of the parade ground, at first all went well as Holtzendorf’s division pushed back enemy skirmishers but then disaster struck. Marechal Soult had unleashed his Corps cavalry under General Guyot (8th Hussars and 11th Chasseurs a Cheval) who caught the cavalry protecting Holtzendorf’s left flank off guard and routed them.

This cavalry fell back upon Holtzendorf’s infantry to their left taking three of his battalions with them, only the Borcke Grenadier battalion held firm. This gallant battalion covered the retreat of the rest upon and through the village of Neckwitz, though the French took General Sanitz, 420 officers and men and an artillery battery. Colonel de Lamothe of the French 36th ligne was also killed here, he had been a veteran of the Egyptian campaign. [4]

Holtzendorf rallied his force badly shaken upon the village of Stobra and played no part in the rest of the battle. General Holtzendorf’s fight had finished by 11.30 am, by which time General Tauentzien had made good his retreat beyond the Dornberg abandoning the villages of Krippendorf and Vierzehnheilgen to the French. Marechal Lannes was quick in his pursuit, his vanguard, the 17th Legere under General Claparede pushed forward rather too boldly taking Krippendorf with ease but was repulsed beyond that village by Tauentzien’s Gettkandt Hussars. Indeed, this regiment was subsequently taken out of fighting line as a result of the casualties it had suffered that day.

At Vierzehnheilgen General Rielle likewise had entered that village with ease but was compelled to quit shortly afterwards as General Grawert’s troops began to make an appearance. Both the divisions of Marechal Lannes were now tiring having been in action since 6.30am, to assist them Napoleon himself had pushed forward a battery of 25 guns to their left. In addition Marechal Ney had arrived with his advance guard of 4,000 men and immediately deployed to Lannes left too. Unfortunately being the impetuous sort Marechal Ney plunged into the fray

without a thought, this could have had disastrous consequences. Because though his cavalry quickly overran a Prussian artillery battery and flung back its supporting cavalry, it found itself faced by overwhelming numbers of other Regiments of Prussian Cavalry rapidly coming up in support of their colleagues. Repulsed, Marechal Ney’s cavalry (3rd hussars and 10th Chasseurs a Cheval) streamed back forcing Ney himself to take

shelter in his infantry squares as the Prussian cavalry attacked.

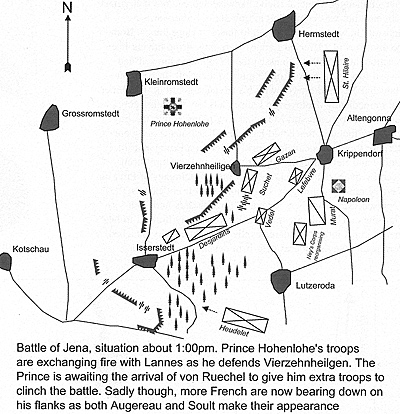

Back around Vierzehnheilgen the climax of the battle was about to be fought as General Grawert’s infantry now approached that village. It was also a moment that presented Prince Hohenlohe with another chance to win the battle but that moment needed an audacious commander, which Prince Hohenlohe was not! General Grawert’s advance was magnificent, in perfect order with colours flying; battalions in echelon with the left leading and as steady as if they were on formal parade at Potsdam. It was an awesome sight. Frederick the Great would have been proud. Cavalry covered both flanks of Grawert’s line of advance; there were about forty-five squadrons of them. If General Seydlitz or Prince Moritz of Anhalt-Dessau (two of Frederick the Great’s redoubtable generals) had been there all would have been well but they belonged to the past.

As Grawert neared Vierzehnheilgen his troops collided with Marechal Lannes’ intrepid though tired men who were attempting to advance beyond the village. Thrown back, Lannes’ men took cover in the houses, gardens and hedgerows of the village and begin a sharp skirmishing fire against Grawert’s troops. Prussian Jägers (Schützen) were deployed to counter this and a confused and costly battle developed within the village but the Prussian Jägers were out numbered and were subsequently driven out. General Grawert ordered the main body of his infantry forward and halted them within musket range of the village, his Colonels began company volleys which forced back Lannes’ skirmishers and Prince Hohenlohe bought up a howitzer battery that soon set the village ablaze.

So far so good. Lannes’ men were tired and had just been bundled back into the village; the advantage clearly lay with the Prussians. Prince Hohenlohe was urged to storm the village by his staff, even Colonel Massenbach who had prevented Prince Hohenlohe’s attack of the 13th now supported this course of action as better then the course

advocated by Prince Hohenlohe who wished to rely on volley fire. But Prince Hohenlohe’s nerve must have failed him, General Grawert’s infantry could and should have stormed Vierzehnhielgen and they may well have broken Lannes’ Corps. And yet, Prince Hohenlohe was uncertain, he felt he did not have enough troops to support such a course of action and wished to await General von Ruechel’s arrival (who Prince Hohenlohe had requested support from earlier that day). Though even if General Grawert had attacked Vierzehnheilgen and had been repulsed the forty-five squadrons of cavalry available-could have covered the withdrawal.

Whatever the reasons for Prince Hohenlohe’s decision, the consequences were to be painful for General Grawert’s magnificent regiments out in the open before Vierzehnheilgen firing their company volleys but subject to the galling fire of Lannes’ skirmishers and artillery, who took a heavy toll upon the unprotected ranks of General Grawert’s regiments. For two hours this went on and whole companies were decimated, dead

and dying lay all around and the once proud regiments of General Grawert’s division were slaughtered to no purpose. Eventually General Grawert’s men began to waver but not before they had repulsed another attempt by Lannes’ men to advance beyond the village.

Meanwhile the Saxons around Isserstadt had been involved in their battle against Marechal Augereau’s Corps. General Zeschwitz’s division had for the most part contributed little to the battle and had stood largely around the Schnecke, a hill to the south of Isserstadt. Now Marechal Augereau’s forces attacked him, General Desjardin’s division assaulted the hill directly from Isserstadt and in the process sustained heavy causalities from the Saxon artillery whilst General Heudelet’s division attacked from the direction of Cospeda in two columns. Gradually Augereau’s forces forced the Saxons back by shear weight of numbers but the Saxons give a good account of themselves before it became obvious that if they did not retreat they would be overwhelmed and captured.

Sadly, General Zeschwitz’s men had only got as far as Schwabhausen and Kotschau when they were finally surrounded and compelled to surrender at about 3.00 pm. General Zeschwitz himself at the head of some cavalry fought his way out but the greater part of his division, despite their valiant fighting retreat from Schnecke were taken prisoner. It was a sad end but the Saxons had been disillusioned with the Prussian alliance and two days later actually switched sides and would become a faithful French ally for the next seven years.

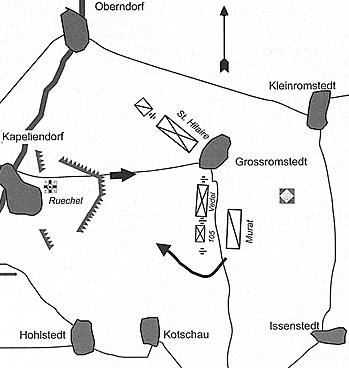

This was, as it turned out, fatal advice. The best General von Ruechel could have done would have been to establish a defensive line

between Kapellendorf and Hammerstadt behind the Sulzbach stream. Which would have stopped the French offensive (at least until nightfall) thus enabling Prince Hohenlohe some time to rally his scattered troops and may well have led to some far-reaching benefits for the Prussian cause. It was another missed opportunity and ultimately cost Prussia Prince Hohenlohe’s and General von Ruechel’s Armies. Instead General von Ruechel led his Corps forward to win a battle that was already lost. Passing through Kapellendorf he deployed his forces in echelon with the centre leading. General von Ruechel’s own cavalry and elements of Prince Hohenlohe’s that had rallied covered the flanks. Once again Prussian regiments advanced with the steadiness of the parade ground.

Advancing uphill from Kapellendorf towards Gross Romstadt, they attracted the attention of French artillery and cannonballs soon began to plough furrows through their ranks. Undeterred the advance continued, officers in particular becoming casualties including General Ruechel himself. French skirmishers and light artillery soon fell back, French cavalry surged forward but was beaten back by General von Ruechel’s supports. Then as the Prussian regiments neared the crest of the hill they were ascending, they were met by a huge mass of French infantry and artillery. A terrific firefight ensured that lasted about twenty minutes, losses were heavy and General von Ruechel’s regiments could do no more. Falling back the Prussian cavalry endeavoured to save them but Marechal Prince Joachim Murat’s cavalry were upon them, the 1st Cuirassiers crushing the Winning regiment and taking 400 prisoners, many other regiments met a similar fate. General von Ruechel’s gallant effort thus suffering the fate of Prince Hohenlohe’s forces, as initial order and controlled retreat degenerated into hasty flight. Their combined forces had been put to the sword; individual units did keep together and fight a successful withdrawal from the stricken field.

The Saxon cavalry and General Tauentzien’s command both accomplished this but in general the Prussian Army that fought so bravely at Jena was routed. It could have been so different.

Jena Auerstadt: A Day of Lost Opportunities Introduction

|

The 14th began with yet more mist and this was to help the French more then the Prussians. For it was concealed from the Prussians, General Tauentzien in particular, the French masses as they collected themselves on the plateau that morning. Indeed, according to Colonel

F.N. Maude, 25,000 men were crowded into a front of less then 1,200 yards and had the Prussian artillery been aware of the target in front of them it is easy to imagine Lannes’ fate. [3]

The 14th began with yet more mist and this was to help the French more then the Prussians. For it was concealed from the Prussians, General Tauentzien in particular, the French masses as they collected themselves on the plateau that morning. Indeed, according to Colonel

F.N. Maude, 25,000 men were crowded into a front of less then 1,200 yards and had the Prussian artillery been aware of the target in front of them it is easy to imagine Lannes’ fate. [3]

Fortunately Ney’s squares held firm despite the enormous pressure they had to sustain. In the end, Marechal Lannes’ cavalry on the direct orders of Napoleon rescued him but Ney’s forces were now rendered ‘Hors de Combat’ for the rest of the battle. Toward the Village of Isserstadt Marechal Augereau was making an appearance and engaging the Saxon elements of Prince Hohenlohe’s Army. The fighting was not easy but General Desjardin’s division took the village of Isserstadt about this time. Having defeated the Prussian light troops in and around that village and pushed back General Cerrini’s supporting Saxon brigade. Which subsequently fell back toward General Grawert’s right. A well timed charge by the French 7th Chasseurs a Cheval took out the Grossmann artillery battery but had little support.

Fortunately Ney’s squares held firm despite the enormous pressure they had to sustain. In the end, Marechal Lannes’ cavalry on the direct orders of Napoleon rescued him but Ney’s forces were now rendered ‘Hors de Combat’ for the rest of the battle. Toward the Village of Isserstadt Marechal Augereau was making an appearance and engaging the Saxon elements of Prince Hohenlohe’s Army. The fighting was not easy but General Desjardin’s division took the village of Isserstadt about this time. Having defeated the Prussian light troops in and around that village and pushed back General Cerrini’s supporting Saxon brigade. Which subsequently fell back toward General Grawert’s right. A well timed charge by the French 7th Chasseurs a Cheval took out the Grossmann artillery battery but had little support.

It was about 1.00pm when General Grawert’s men began to fall back upon Prince Hohenlohe’s order, General Grawert himself wanted to hold on where he was until General von Ruechel arrived. At first all went well and discipline held as the regiments retired as if on parade but suddenly at 2.00pm, the left and centre of Prince Hohenlohe’s line broke and even though Prince Hohenlohe’s cavalry tried to provide cover. The French cavalry of Marechal Prince Joachim Murat were upon them, eleven cavalry regiments strong, which Prince Murat led contemptuously wielding a mere riding whip, pursued the fugitives of Prince Hohenlohe’s line until brought to abrupt halt by the sight of fresh enemy troops advancing to the attack. These troops were General von Ruechel’s Corps.

It was about 1.00pm when General Grawert’s men began to fall back upon Prince Hohenlohe’s order, General Grawert himself wanted to hold on where he was until General von Ruechel arrived. At first all went well and discipline held as the regiments retired as if on parade but suddenly at 2.00pm, the left and centre of Prince Hohenlohe’s line broke and even though Prince Hohenlohe’s cavalry tried to provide cover. The French cavalry of Marechal Prince Joachim Murat were upon them, eleven cavalry regiments strong, which Prince Murat led contemptuously wielding a mere riding whip, pursued the fugitives of Prince Hohenlohe’s line until brought to abrupt halt by the sight of fresh enemy troops advancing to the attack. These troops were General von Ruechel’s Corps.

General von Ruechel’s Corps met the fugitives of Prince Hohenlohe’s command near Frankendorf, asking the passing Colonel Massenbach how he could best help he was given the advice: ‘Now only through Kapellendorf .’ [5]

General von Ruechel’s Corps met the fugitives of Prince Hohenlohe’s command near Frankendorf, asking the passing Colonel Massenbach how he could best help he was given the advice: ‘Now only through Kapellendorf .’ [5]