Jena Auerstadt

A Day of Lost Opportunities

Battle of Saalfeld

by Patrick E. Wilson

| |

The Prince weakened his centre as a result so that when the French then attacked there, they broke through and it was here that the gallant Prince Louis met his end in one to one combat with Sergeant Guindel of the 10th Hussars. The death of Prince Louis led to the collapse of his advance guard division, many were captured in the French pursuit and as a formation it was thoroughly shaken, being of little use at the Battle of Jena-Auerstädt four days later. The fact that the majority of those engaged at Saalfeld were Saxons did not adhere that nation to the Prussian cause, indeed they seem to have become rather despondent as a result and must have felt that the initial weight of the war had fallen on them alone. The death of Prince Louis was of course a real shock to the Prussians themselves; the fact that the combat of Saalfeld should not have happened must have been another area of concern for them. It seems to me that Prince Louis was to a certain extent let down by his immediate superiors as he was only informed at 10.00 am on the 10th October that he should hold fast at Rudolstadt on the other bank of the Saale. At this time he was already heavily involved fighting Marechal Lannes and although it is possible he could have broken off, perhaps he felt he would be able to hold on until night fall. Unfortunately this was not to be the case and Prussia lost a potentially excellent soldier. Saalfeld had another effect upon the course of war though, for it jolted the Prussian commanders into action and positive action at that. A definite plan was at last formulated, the need to concentrate was recognised and the orders for this were issued without much debate. Prince Hohenlohe was to concentrate between Jena and Weimer to cover the Duke of Brunswick’s concentration upon Weimer itself, whilst General von Ruechel’s troops made for and reached Erfurt. By the evening of the 11th October Prince Hohenlohe held both Jena and Lobeda, the Duke of Brunswick had assembled his army at Weimer on the river bank of the Ulm and General von Ruechel was on the left bank, although von Ruechel did have some detachments facing west toward Fulda. These detachments would not made it back for the battles of 14th October. French March

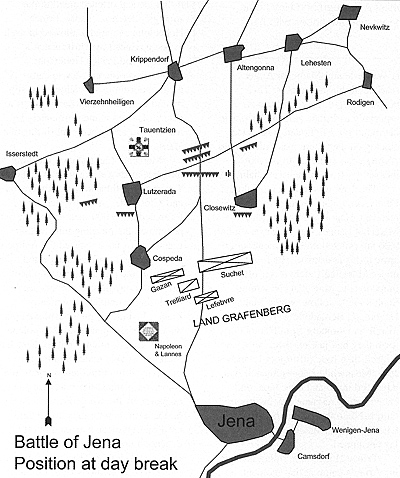

On the French side Marechal Lannes had advanced to Neustadt, Marechal Augereau had replaced him at Saalfeld. They had orders to march for Jena via Kahla. Marechals Soult and Bernadotte were about Weida and Gera, Marechals Davout and Ney about Mittel Polnitz and Gera respectively. The 12th and 13th October are of great significance, for they presented the Prussians with a great opportunity for a significant victory and also saw the period when Napoleon realised where the Prussians were and the fact that he would have to fight a battle two days before he had planned. If we look at the map we can see that Napoleon’s left wing, Lannes and Augereau, were in grave danger from a determined thrust from the Prussian armies on the other side of the Saale. This was somewhat precipitated (though unconsciously at that time) by Marechal Lannes who advanced in compliance with his orders upon Jena via Kahla. He collided with Prince Hohenlohe’s advance guard at Goeschwitz and Winzerle on the 12th and drove General Tauentzien back upon Jena itself. That night Lannes was at Winzerle and Marechal Auger reached Kahla in support. Their positions were very precarious, especially as Prince Hohenlohe was in the mood for a fight and if he acted quickly enough there was little Lannes or Augereau could do to prevent themselves from being overwhelmed. The 13th was to be a crucial day. Firstly, after studying the reports he’d received Napoleon realised that Marechal Lannes was in danger and at 9.00 am ordered other elements of his army to his assistance. His foot Guards under Marechal Lefebvre set off immediately, Marechals Ney mind Soult were to follow, whilst Marechals Davout and Bernadotte were ordered to march on Dornberg from Naumbourg, a town they had just reached. Napoleon himself then rode off to join Lannes at Jena. Meanwhile Lannes himself had advanced up to and took Jena, only encountering resistance as his troops climbed onto the plateau behind Jena where Prince Hohenlohe’s Army now lay encamped. Prince Hohenlohe, riding through his Army’s camp at that moment, heard the firing between General Tauentzien’s outposts and Lannes’. Immediately perceiving the cause he ordered his reserve infantry and four cavalry regiments forward to attack and drive Lannes back across the Saale, an attack that would undoubtedly have been successful as Lannes had under 20,000 men. At that moment though disaster struck for Prussia in the form of a message from the Duke of Brunswick, the nominal Commander-in-Chief, delivered by Prince Hohenlohe’s own Chief of Staff, Colonel Massenbach.

Sadly Prince Hohenlohe eventually allowed himself to be convinced by Massenbach’s argument and Prince Hohenlohe’s reserve was ordered back to camp. A great opportunity was allowed to slip by and General Tauentzien was left to contain Lannes alone, fortunately he was able to easily accomplish this that afternoon. Marechal Lannes upon reaching the plateau above Jena saw as General Tauentzien fell back upon Lutzereoda and Closewitz, an army that he estimated at 40,000 men and as the sun penetrated the morning mist that day. Lannes must have realised the full peril of his situation and have expected to be swept off the plateau at any moment. But as the day progressed this seemed increasingly unlikely, eventually Lannes had all his men positioned on the edge of the plateau and Napoleon and his Guard infantry joined these that evening. Unable to account for the inactivity if the Prussians, Lannes and Napoleon planned their defence against an attack by the whole Prussian Army on the 14th, hoping they could hold until reinforcements arrived but it all depended upon the speed of any Prussian offensive. They were unaware that Prince Hohenlohe been forbidden to make any offensive move and that the Main Prussian Army was then already marching for the Elbe via Kosen and Halle. The 14th would eventually lift the veil but the morning still held dangers for Napoleon’s Army, especially Lannes and as we shall see later, Marechal Davout. Jena Auerstadt: A Day of Lost Opportunities Introduction

The Prussian Army of 1806 The Campaign Battle of Saalfeld Battle of Jena Battle of Auerstadt Conclusion Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #63 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 2002 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com |

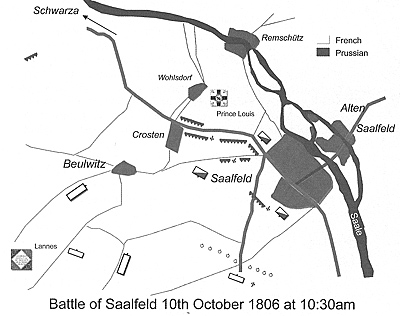

The action of Saalfeld was a mismatched encounter that pitted Prince Louis’ 8,300 men against the 14,000 Frenchmen of Marechal Lannes, probably the finest commander Napoleon ever had. Prince Louis deployed his force with the river Saale at its back and did not occupy the outlying villages; his major concern was his right flank as it covered his line of retreat. Lannes of course, exploited Prince Louis’ mistakes as he became aware of them and concentrated his main attack towards Prince Louis’ right.

The action of Saalfeld was a mismatched encounter that pitted Prince Louis’ 8,300 men against the 14,000 Frenchmen of Marechal Lannes, probably the finest commander Napoleon ever had. Prince Louis deployed his force with the river Saale at its back and did not occupy the outlying villages; his major concern was his right flank as it covered his line of retreat. Lannes of course, exploited Prince Louis’ mistakes as he became aware of them and concentrated his main attack towards Prince Louis’ right.

Pierre Francois Charles Augereau by Johnson after Lefebvre, Marechal of the Empire, Commander of the French VII Corps at Jena.

Pierre Francois Charles Augereau by Johnson after Lefebvre, Marechal of the Empire, Commander of the French VII Corps at Jena.

Prince Hohenlohe was to refrain from offensive action and maintain his present position; thus acting as a flank guard as the Main Army of the Duke of Brunswick marched from Weimer to Kosen. Massenbach asserted that Prince Hohenlohe’s contemplated attack upon Lannes was a violation of these orders. But Prince Hohenlohe demurred, arguing that it was the right course of action to take, as strategic defence did not rule out tactical offence, especially if that tactical offence aided in the strategic defence.

Prince Hohenlohe was to refrain from offensive action and maintain his present position; thus acting as a flank guard as the Main Army of the Duke of Brunswick marched from Weimer to Kosen. Massenbach asserted that Prince Hohenlohe’s contemplated attack upon Lannes was a violation of these orders. But Prince Hohenlohe demurred, arguing that it was the right course of action to take, as strategic defence did not rule out tactical offence, especially if that tactical offence aided in the strategic defence.