Battle of Vera 1813

"Please God,

I Will Keep the Bridge"

The Battle at the Bridge

by Rifleman Moore

| |

A worried Smith then left to see Colbourne, who was equally dismayed at Skerrett’s order concerning the bridge. Colbourne agreed to immediately support Cadoux should firing be heard. Smith - still suffering under his premonition of impending disaster - could now only return to sit and fume in front of the headquarters fireplace. Clausel read Soult’s reply to his second message in the rain of the late afternoon. Soult confirmed Clausel’s wish to retreat immediately, slip away out of the closing pincers and support the troops at Behobie, leaving one Division before Vera on the ‘French’ bank of the River Bidassoa to watch the bridge. There was just time enough to do it - Clausel’s troops retired at once leaving a rearguard, a Brigade under General Van der Maesen, to keep any pursuing Allies at a respectable distance. The main body reached the Vera fords before dark and managed to cross over. It did not however occur to Clausel that by the time Van Der Maesen’s troops arrived, the fords there would probably be well under the rising flood water and hence totally impassable.

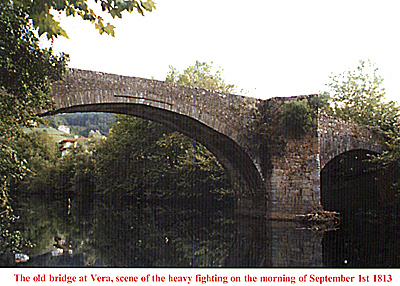

When the French rearguard arrived in the darkness and pouring with heavy rain, Van Der Maesen was met with a report that several French soldiers had an hour earlier been drowned attempting to cross by the fords, by now flowing far too deep and too fast to be used. The French rearguard was forced to move upstream to try to find the bridge at Vera and cross the river there to avoid encirclement the next day. Just before 3am, the morning of September 1st 1813, a courier delivered a message to Skerrett’s headquarters from General Karl Von Alten. Alten confirmed the reports that the French were cut off on the ‘Spanish’ side of the Bidassoa due to the floodwater and would certainly try to get over the bridge at Vera, where Skerrett was well-placed to stop them. Smith after hearing the message from Von Alten went to persuade Skerrett to amend his dispositions and move into Vera in force. Skerrett refused to do so, and became obstinate in the face of Smith’s persistence - the two men then became involved in an argument matched only in fury and velocity by the heavy rain still pounding on the pantiles above their heads. The heavy rain also prevented the doubled sentries at the bridge from hearing the approach of a stealthy French scouting force. The corporal and the guard were surprised and killed by the French before they could give the alarm - the French silently signalled back to the waiting troops who then slipped forward and began to cross the twelve-foot wide, fifty-yard long bridge over the raging torrent. Suddenly a terrific cheer went up from the other side, the windows of the houses filled with a blazing volley from the rifles of Cadoux’s men, stopping the French in their tracks and hurling many back and over the parapet of the narrow bridge. A second cheer, and as the riflemen in the house quickly reloaded a sword-bayonet charge came in onto the bridge to push the French back onto the other side. A scene of furious hand-to-hand combat, with some French soldiers trying to fight through the front ranks trying to clamber over them to get away from the flashing bayonets and rifle-butts of the screaming greenjackets. Smith and Skerrett stopped arguing as the blast of the volley at the bridge was heard. Smith turned and bolted for his horse, leaving Skerrett standing there. As Smith reached the 2/95th, he saw them already under arms and moving off towards the sound of the firing. The scene at the bridge was terrible - Cadoux personally led the fighting at the barricaded near end of the bridge, with the riflemen behind and above him firing from the cover of the dry upstairs rooms of the houses into the dark mass of the French on the bridge and the far bank. Van Der Maesen ordered his troops to line the bank and any with dry muskets and ammunition to begin firing across the river ; Clausel’s troops in the Reserve beyond Vera upon hearing the shooting sent troops into the village to flank Cadoux at the bridge and also to prevent any support arriving from the Light Division, dragging two field guns along with them. Cadoux at this point received a message from Skerrett, ordering him to withdraw at once. Cadoux sent the message back for confirmation, adding that although in apparent danger of being surrounded, he was in a strong position blocking the bridge and doing the French great damage as their muskets were almost all now soaking wet, the threatening two French artillery pieces were not able to get close enough to do serious damage to the houses, and he was still able to hold the bridge if Smith arrived soon with the 52nd to keep the French from both attacking through Vera in strength and pushing them away from the bridge. Before Smith arrived, Skerrett confirmed his order to retire immediately. Cadoux, uncertain now through these messages that Smith was ever to reach him, quickly made preparations for a fighting withdrawal back through narrow, dark, wet streets crammed with French soldiers, adding to one of his subalterns that “But few of us, I think, will reach the camp …” As the rifleman burst out of the houses into the streets, the firing died away as Baker rifles were quickly soaked by the rain. The clashing of weapons, stifled cries, the grunts of men and the low thud of bodies hitting the ground could be heard for a short time, before dying out to be replaced with the only sounds being panted curses and nailed boots moving quickly over cobbled streets.

As Smith arrived, close behind the first soldiers of the 95th and 52nd, he realised Cadoux had been overwhelmed and they were too late. The French had escaped over the bridge, leaving only dead and wounded men and a handful of stragglers. Grimly noting the carnage at the bridge almost blocked by dead men, the Rifles quickly pursued the French through the village, forcing them to push their guns down into the river along a seventy-yard long stretch to prevent immediate capture. In the growing light, Smith found Cadoux where he had fallen, killed instantly by a shot through the head at the bridge, his ring torn from his finger, his body surrounded by the other officers and sixteen dead and over forty wounded greenjackets, amidst a layer of over two hundred dead and trampled Frenchmen, one of whom was later found to be General Van der Maesen. When Smith was told about Skerrett’s order to Cadoux to withdraw, he set his jaw, firmly closed his eyes, clenched his fists at his sides and ground his teeth together in tearful anguish. If not for that … he would have kept the bridge, by God! The rushing river was seen to be partly blocked a short way downstream at a bend by the bodies hurled over the parapet of the bridge by those following behind struggling to get over with the artillery ; as the water level fell, a veteran rifleman from a party collecting bodies for burial pointed out brown trout nibbling at the corpses of the Frenchmen still in the water, making his redcoated comrade shudder and turn away. EpitaphThe war moved on - the Light Division a month later in October 1813 attacked and captured the lofty Rhune Mountain and heights above Vera, before descending beyond into France. General Skerrett left the army shortly after this event to ‘take possession of a large inheritance’. He was killed in action a year later in 1814 at Bergen-Op-Zoom. Harry Smith went on with his faithful wife Juana to fame and fortune with one of the longest and widest service records of any serving British soldier. Harry met Juana after the storming of Badajoz in 1812 and they are interred together at Whittlesey. A old local priest at Vera -- no longer incumbent -- recorded twenty years ago that Daniel Cadoux and the riflemen who fell at the bridge at Vera were buried in the churchyard, in two pits. Two rough and unmarked stones were later placed by an unknown person or persons to mark their final resting-place ; later still a memorial to them was set upon the bridge itself, with an inscription in both English and Spanish. A rifleman of the 2/95th - one of the first on the scene -- stole the large emerald ring from Daniel Cadoux’s dead left hand but was discovered and arrested when he tried to sell the ring to an officer a short time later. He was subsequently punished. You can still easily find all the places mentioned in this article today : the San Marcial hill hermitage, the old bridge at Behobie and the fords on the east side of the Great Gorge where the French crossed the Bidassoa, the Light Division positions on the Santa Barbera heights south of Vera - and of course the old village bridge, complete with the memorial to Daniel Cadoux and his soldiers, all set amidst some of the most spectacular scenery you’ll see in the Peninsula. ‘Rifleman Moore’ is a battlefield tour guide for The Peninsular War and Waterloo Campaigns, for Midas Tours. The sites mentioned form just one part of ‘Over The Hills and Far Away / Walking the Pyrenees, 1813-1814’, just one of the Napoleonic period tours from MIDAS TOURS (Telephone 01963-371550 for more details). More Battle of Vera 1813 Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #62 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 2002 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com |

The old bridge at Vera, scene of the heavy fighting on the morning of September 1st 1813

The old bridge at Vera, scene of the heavy fighting on the morning of September 1st 1813

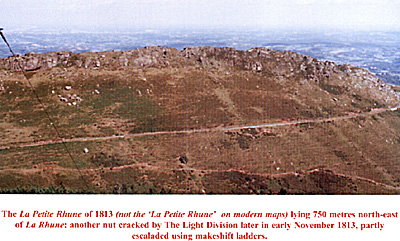

The La Petite Rhune of 1813 (not the ‘La Petite Rhune’ on modern maps) lying 750 metres north-east of La Rhune: another nut cracked by The Light Division later in early November 1813, partly

escaladed using makeshift ladders.

The La Petite Rhune of 1813 (not the ‘La Petite Rhune’ on modern maps) lying 750 metres north-east of La Rhune: another nut cracked by The Light Division later in early November 1813, partly

escaladed using makeshift ladders.