Eylau: A Russian View

Battle of Hof

by Patrick E. Wilson, UK

| |

Rallying quickly, the Hussars counterattacked and drove back the French Dragoons once again. Murat then attacked with General Count d’Hautpoul’s Cuirassiers, who caught the Dragoons (St. Petersburg Regt.) off guard and drove them in wild confusion upon the Kostroma Musketeers who were broken and terribly cut by the pursuing French Cuirassiers and lost two of their standards. His centre broken, all Barclay de Tolly could do now was see that his left and right wing Jäger regiments fell back before they were surrounded and overwhelmed. The regiment on the right was already surrounded but succeeded in bayoneting its way out. Colonel Dolgorucky brought up five fresh battalions to stabilise the centre and bring to a halt d'Hautpoul's Cuirassiers. In this Dolgorucky was undoubtedly helped by a fine charge by a young officer called Gallitzin at the head of two Russian Cuirassier regiments. Unfortunately young Gallitzin was killed but he and Dolgorucky had saved the day for Barclay de Tolly and thus the Russians held on until nightfall. Again losses in this action were high, about 2,000 Russians and certainly more then 2,000 French, Soult gives his losses as 1,960 men. [5]

The losses to the French Dragoons and Cuirassiers most have been substantial. Indeed such was the resistance that Napoleon had met with at Hof that he thought that a battle would be fought at Landsberg the next day and ordered both Ney and Davout to support him at Landsberg. But Benningsen had no intention of fighting at Landsberg as he had already selected Preussisch-Eylau, as his battlefield, his heavy artillery was already on its way and L’Estocq’s Prussians had been ordered there. Benningsen’s army marched at dusk on the 6th, which was just as well as it was difficult moving through Landsberg and one column had to back track when it found its

designated route blocked up by snow. Nevertheless by 12.00 on 7th the army had gained its position to the rear of Preussisch-Eylau, a division though had been left in the town to support Bagration’s hard pressed rearguard and to occupy that town after the rearguard had retired to its positions within the army. The condition of Benningsen’s army on its arrival at Preussisch-Eylau must have caused some alarm as it had been on the retreat from Jonkowo for four successive nights.

The means of sustenance available in such a sparsely populated country proved utterly inadequate for the needs of Benningsen’s famished legions, the troops were also fatigued by the narrow, winding, snowed up roads by which they had had to march. But for a true picture of the state of Benningsen’s army let me quote an officer

of the Azov Musketeer regiment:

‘We have just arrived. This is the first moment I have had since leaving Jonkendorf (Jonkowo) in which to bring my dairy up to date. I am so numbed, mentally and physically, by hunger, cold, and exertion, that I hardly have the strength or the desire left to write this down. No army could suffer more then ours has done in.these few days. It is no exaggerated calculation to say that for every mile between Jonkendorf and this place the army has lost 1,000 men who have not come within sight of the enemy. And the rearguard! What terrible losses it has suffered in those perpetual fights! The way they go about things is incredible and quite irresponsible. Our generals seem to vie with one another in a methodical undoing of the army. The disorder and confusion passes

human conception. Benningsen drives ahead in his carriage as usual, and the divisional generals follow their commanders example General staff officers and column guides are seldom in their appointed places, consequently it often happens that all detachments of the army are marched off at the same moment and all try to take the same road. This results in the last divisions having to stand half a day or night in the snow with empty stomachs and wet feet. We left many dead and many sick men behind us on the road in this way. It takes a patient, healthy Russian to stand all this. We have survived so far through being constantly on the move and by the cold weather, but the consequences will be terrible. Often during a night march through a wood or a defile the troops would be obliged to go in single file passed some trifling object which blocked the way, because no one gave the order to remove the obstacle . . . The poor soldiers glide about like ghosts. You see them asleep on the march with their heads resting on their neighbours. I myself arrived half-asleep and half-awake, and the whole retreat seems more a dream than reality.

“The patience which our soldiers display in this business is truly commendable, and better than any philosophy. To one who has served in other armies this sort of thing is doubly grievous, because he knows by experience that it could be and ought to be different. Is there any precedent for reducing an army like ours to such a condition! In our regiment (the Azov), which has not seen the enemy and was complete when it marched across the frontier, the companies are reduced to 26 or 30 men apiece. The grenadier battalion scarcely musters 300 men, the other two are even weaker. Not all the regiments have lost so many, it is true, as they had fewer recruits. Most of those that we left behind are in fact recruits and hard bargains. One could almost credit Benningsen with the desire to retreat still further, did the state of the Army permit it. As however, it is so weakened and exhausted as to render a forced march on these same lines practically impossible, he has at last decided to do what he ought to have done long ago to fight!” [6]

The afternoon and evening of the 7th February would see more serious fighting as Bagration fulfilled his orders and a serious engagement for the possession of Preussisch-Eylau developed. Bagration deployed most of his rearguard on the frozen Tenknitten See as it blocked the main route of the French advance. He had a battery of guns, two grenadier and two musketeer regiments, plus two Jäger regiments that he deployed in skirmisher order and the St. Petersburg Dragoons eager to avenge themselves for the dismal performance at Hof. Immediately in support of Bagration was the Russian 8th Division, which was deployed between the village of Freiheit and the Langer See. A battery was deployed to its left and cavalry deployed on both flanks, 25 squadrons behind the Waschkeiten See and 10 squadrons to the north of Bagration’s position.

Eylau: A Russian View by Patrick E. Wilson, UK

|

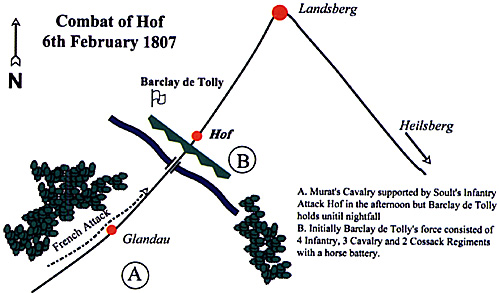

Barclay de Tolly deployed his troops at Hof in the following manner; a Jäger regiment in the woods to his right, another in the woods to the left, both supported by

Hussars. In the centre behind a bridge over a marshy stream he had a Hussar regiment drawn up and supported by two Musketeer regiments and another cavalry regiment. The French began their attack at about 3.00pm with skirmishers attacking Barclay de Tolly’s left, he countered this by moving one of his Musketeer regiments to support his Jägers and drove the French Skirmishers back. Next the Grand Duke of Berg (Marechal Joachim Murat to you and me) with General Klein’s Dragoons stormed across the bridge to Barclay de Tolly’s front but as they were not deployed they were quickly bundled back across by Barclay de Tolly’s Hussars. Barclay de Tolly’s other regiment, a regiment of Dragoons, carried too far by the adrenaline of the combat, pursued the French across the bridge and was in its turn bundled back across breaking the Hussar regiment and allowing the French Dragoons to attack across the bridge until they were brought to halt by the Russian horse batteries and the squares of the Kostroma Musketeer regiment.

Barclay de Tolly deployed his troops at Hof in the following manner; a Jäger regiment in the woods to his right, another in the woods to the left, both supported by

Hussars. In the centre behind a bridge over a marshy stream he had a Hussar regiment drawn up and supported by two Musketeer regiments and another cavalry regiment. The French began their attack at about 3.00pm with skirmishers attacking Barclay de Tolly’s left, he countered this by moving one of his Musketeer regiments to support his Jägers and drove the French Skirmishers back. Next the Grand Duke of Berg (Marechal Joachim Murat to you and me) with General Klein’s Dragoons stormed across the bridge to Barclay de Tolly’s front but as they were not deployed they were quickly bundled back across by Barclay de Tolly’s Hussars. Barclay de Tolly’s other regiment, a regiment of Dragoons, carried too far by the adrenaline of the combat, pursued the French across the bridge and was in its turn bundled back across breaking the Hussar regiment and allowing the French Dragoons to attack across the bridge until they were brought to halt by the Russian horse batteries and the squares of the Kostroma Musketeer regiment.