Spotlight on

L'incomparable 9e Leger

Profile and Unit History

by Terry Crowdy and Martin Lancaster,

Illustrations by Terri Julians

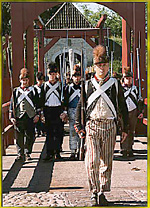

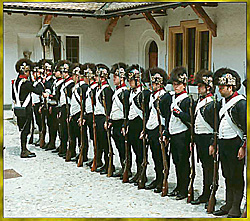

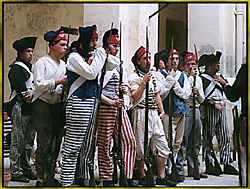

Photos by kind permission of 9è Légèr and Mëck Hoffmann

| |

The men that served in the 9è Légère traced their history back to the year 1784 when a battalion of light infantry, or chasseurs was added to the 4è régiment de Chasseurs à Cheval. Together these two bodies formed the Chasseurs des Cévennes in the city of Carcassonne in the Languedoc region of France. As colonel, the Viscount de Toulongeon spent much of his time overseeing the training of the cavalry arm of his regiment, especially so after lieutenant-colonel de Lardenelle [the officer directly responsible for the mounted wing of the regiment] was imprisoned! Therefore Toulongeon gave his other lieutenant-colonel, the Chevalier de Barroussel [see profile] carte blanche to go away and form the required infantry battalion from scratch as he saw fit. With the aid of the veteran avant-garde soldier, Major de Villionne, de Barroussel scoured his contacts in other regiments to collect a body of officiers and sous-officiers who were both experienced, and in the case of the most senior officiers at least, veterans of the petite-geurre.

For the first two winters, the chasseurs des Cévennes were trained rigorously by Major de Villionne and his volcano-mouthed adjudant, Christian Kuhmann. Together these two men whipped the youngsters into shape and built up their strength, while paying a lot of attention to target shooting - something the battalion was noted for in early inspection reports. In 1786 the regiment moved up towards the border, being garrisoned in the area around Metz, where it completed its training and conducted avant-garde type exercises to improve co-operation between both arms.

Outsider

Despite de Villionne's hard work he was not offered the promotion he deserved and an outsider was bought into replace de Barroussel: The new lieutenant-colonel was a bad apple from the start. Although a very experienced soldier he did not offer the stability needed at the top in such a dramatic period of change. He was the classic adventuring soldier, having served as a volunteer in America, Holland and Russia. He took his new command, was awarded the Croix de Saint-Louis and by the end of the year had fled the country as one of a growing band of disgruntled émigrés, gathering over the border in Koblentz, ready to march on Paris and restore the beleaguered King's God-given rights.

For the next two years the 9è slowly but steadily learned the art of war first hand in a bewildering succession of advances, retreats, victories and reverses. However, in spite of the chaos around them, the battalion steadily built up a reputation as a reliable avant-garde force.

After distinguishing themselves at Neerwinden [18th March 1793] the 9è bataillon, [now under the leadership of de Blondeau] returned for a period of rest at the camp at Maulde.

It is unclear who in the battalion knew exactly what was going on, but the plot failed and next morning the traitors were forced to flee. In a crunch speech, de Blondeau lined the battalion up and told them he was going over to the enemy because he could not serve the lunatics in Paris any longer - did anyone want to go with him? A few men did, leaving the senior capitaine, Mathieu Labassée [see profile] to pick up the pieces and inform headquarters what had just happened.

Being an aristocrat, it took a lot of courage for Labassée to walk into headquarters and tell the feared People's Representatives that his lieutenant-colonel and a portion of the men had just turned traitor; but his honesty and frank speaking saved him from a trip to Paris and a Jacobin haircut.

From this point onwards, the 9è went from strength to strength. The gaps in the officer corps caused by casualties, transfers and desertions were all filled by sous-officiers who had served in the battalion under de Barroussel. Although a little rough around the edges and not schooled in theory, these men proved to be an excellent corps of officers over the coming years. In early 1794, following the latest military reforms, the battalion was amalgamated with two other battalions of volunteer chasseurs, which together formed the 9è demi-brigade légère, under the command of Chef de Brigade Michel Eirisch, an aide de camp of Général Michaud.

Until the end of the War of the First Coalition, the 9è légère served under the celebrated Général Marceau in the Armée de Sambre et Meuse. In a period of near continual engagements the 9è Légère fought countless actions in which they continually merited the distinction of their young General. Badly supplied and short of men, Marceau avoided pitched battles against the numerically superior enemy, but instead waged a petite geurre, exactly the kind of fighting de Barroussel had once taught the young men who were now officers themselves.

In 1798 France launched two expeditions: one to Ireland and one to Egypt. This provoked a new war against Russia, Austria, England and Turkey, which among other things saw a resurgence of Royalist rebels in the Vendée region of France. By 1799, the Directory government of France was in absolute chaos; the country was practically bankrupt, the army was in tatters and on the retreat almost everywhere. The expedition to Ireland had been a disaster; Bonaparte was cut off by the British Royal Navy in Egypt; the French even seemed to be provoking a conflict with their fellow republic, the United States: And all the while, what were the 9è Légère instructed to do? Nothing.

They sat in Paris, with mounting debts, a large number of desertions among new recruits, still waiting for the fabled invasion of England to begin. Stupidity and waste it seems were the order of the day. Somehow though the Allies just could not deliver the final blow and as Bonaparte was being rowed ashore in the south of France [having come to save France, or having deserted his army in the field - depending upon your point of view] the situation stabilised somewhat. In this breathing space, Bonaparte returned to Paris and took control of a country that wanted nothing but peace.

The day before Bonaparte's Brumaire coup d'état began, the 9è Légère were seemingly remembered about and while one battalion was sent off towards Strasbourg, the main part was sent down to deliver the knock out blow to the Vendée. Therefore they missed the political fireworks in Paris and were not on hand to help 'throw the lawyers in the river' with the rest of the Paris garrison. They did not escape Bonaparte's attention for long though. Cafferelli's one legged brother Maximillian, had been the chief engineer of the Egyptian expedition. While besieging the town of Acre, Max had his arm shot off and soon after died. In recompense to the Cafferelli clan, Auguste was taken from the 9è and made adjudant-général of the newly formed Garde des Consuls. This left Labassée finally in charge of the 9è Légère: it would be under his command that the 9è had their finest hour.

Marengo

The Division Boudet, with the 9è Légère at its head, had started the day some way off and did not arrive in the field until around five o'clock in the evening. Under the command of Bonaparte's trusted friend, Général Desaix, the 9è Légère were launched at the advancing Austrians to hold them off while the army recovered its composure. The First Austrian regiment [IR 11 Wallis] broke after being hammered by the 'violent' fire of the 9è Légère.

The Austrians retaliated and brought up dozens of guns and the remains of Lattermann's Grenadier brigade to smash the 9è Légère away. Desaix ordered them to fall back into line with the rest of the army, a feat they performed with remarkable discipline and control under such heavy fire. Then, just as the Austrians believed they had swept this new threat away, Desaix rode to the head of the 9è's Carabiniers and ordered the 9è Légère to turn about and charge the advancing Grenadiers.

His victory secure, Bonaparte returned to Paris in triumph. However, the war was not yet fully over and the 9è Légère did not return home for another year. When they did arrive in Paris they were feted and covered in rewards - the most spectacular of which being three specially commissioned flags with the legend 'L'INCOMPARABLE' emblazoned in the centre of a dramatic sunburst. However the time in Paris was not a happy one, a depression set over the men suddenly bored by the peacetime parades and garrison duty. The uniforms were ragged, discipline was edgy, fights were breaking out with the Garde des Consuls who were merely elite as opposed to incomparable. A lot of the 9è Légère's men were getting old now and the wars of liberty as they were now remembered, had taken a heavy toll. Suicides were common place, as was desertion - it was time for a change.

On the 19th July 1803 Claude Meunier [see profile] took over command from Labassée who had recently been promoted to Général de Brigade. The 9è Légère was moved out of Paris to the famous camps at Boulogne where it spent the next two years getting its self in shape for yet another war. When on the 28th August 1805, the Division Dupont, with the 9è at its head, marched out on the road to Bavaria, Meunier had honed his regiment into a formidable machine. The glory years awaited them.

Even a summary of the actions fought by this regiment in the Empire period would be exhausting. The names of battles reeled off one after the other. Out numbered five-to-one at Haslach; pitted for the first time against the Russians at Durrenstein, the 9è Légère missed Austerlitz while guarding Vienna, Napoleon considering that they had already played a grand enough role in the campaign. They again missed out in Jena and blamed Bernadotte for his inactivity. They caught up with the Prussians at Halle and took their revenge in bloody fashion. At Friedland, Ney put himself at the head of the second battalion and with a cry of 'Vive L'Empereur launched a counter attack against the Russians which knocked back the advancing Russian columns only ending when, in an instant almost 300 Chasseurs and Carabiniers were gunned down by a massed Russian battery.

On the eve of the battle of Talavera the 9è Légère staged an audacious attempt to seize an important hill from the Allied army under the cover of darkness. One 9è officer [Girod de L'Ain] recalled what happened:

Unfortunately for the 9è légère, the two supporting regiments had lost their way in the darkness and so they were left alone to face a massive counterattack. Realising the impossibility of holding the hill, the surviving chef de bataillon ordered the regiment to pull back half way down the hill where they reformed. Once this was done volunteers were sent back up the hill to collect the wounded, including Colonel Meunier who had been shot three times. No one, not even the British, blamed the 9è Légère for pulling back - most were astounded that the attack had been made in the first place and only honour was heaped upon the survivors.

The 9è Légère was also unfortunate enough to have its third battalion in Badajoz when that town was infamously assaulted on the night of the 5/6th April 1811. The British assaulted the breeches their siege artillery had forced in the walls, under the cover of darkness and were butchered as they forced their way into the town -- each French soldier was armed with three loaded muskets in order to gun down the redcoats quicker than they could come up. Eventually though, the walls were forced and chaos broke out in the streets. The survivors of the 3rd battalion managed to reach the security of Fort San Christoval where they held out before surrendering the next day. The losses on both sides that night where terrible, the third battalion [under the command of chef de bataillon Billon] losing half its men in the fighting, the remainder carried off as prisoners of war.

While in Spain, the depots of the 9è Légère produced a fourth battalion which served with the Grande Armée in 1809. This battalion formed part of an ad-hoc regiment that fought at both Essling and Wagram. After the loss of the third battalion at Badajoz, a new battalion was formed to replace it, also a fifth and sixth battalion. While the fifth remained in the French town of Longwy and acted as a depot, the 4th and 6th took part in the campaigns in Germany after the Russian disaster. Although formed mainly of young conscripts, the men served well and fought a stupendous amount of actions during the retreat back into France. Their battle honours included, Lutzen; Bautzen; Wurschen; Katzbach; Culm; Leipzig; Hanau; la Rothière; Laon and finally the last stand at Paris.

Remnants of 1814

On the 30th March 1814, the remnants of the third battalion stood with Marmont's 6th Corps at Belleville. Fighting furiously, they held off the Russians, assault after assault until Marmot, after receiving the permission of Napoleon's elder brother, King Joseph, began armistice talks.

On the 1st of April, after what Marmont remembered was their 67th engagement of the campaign, the third battalion of the 9è Légère lined up for role call. Of the surviving nine officers and 37 men, only 27 were still able to stand in the ranks. As Napoleon was escorted to Elba and the Bourbons reclaimed their throne, the shattered remnants of the 9è Légère made their way home to Longwy, to lick their wounds and dream of better days.

As everyone knows, there was still one final twist to the tale. On the 20th March 1815, Napoleon once again sat on the throne of France: News of his arrival sent raptures of joy through the ranks of the 9è Légère. In a letter to his sister in Philippeville dated 'Longwy, 9th April, 1815,' Capitaine Cardron of the 9è recalled how he and his comrades had greeted the news:

I almost forget to tell you a thing that has given us great pleasure: the day that we raised the tricolour cockade, we took up arms. We were on the square where the brave Colonel Deslon resides. Without knowing why, he formed us up and led us to beneath his windows. Imagine seeing 80 officers in two ranks, asking one another what was going on? What was it? In the end we were filled with worry, when we saw Colonel Deslon appear, holding something in his hands? You would not guess what in a hundred years..... Our Eagle under which we had marched so many times to victory and that the brave Colonel had hidden inside the mattress of his bed when that rotten race of Bourbons ( an expression of the prince of the Moskowa) ascended to the throne and exchanged our cherished colours to those that reminded us of slavery. At the sight of the cherished flag cries of 'Vive l'Empereur!' could be heard; soldiers and officers, all overwhelmed, wanted not only to see, but to embrace and touch it; this incident made every eye flow with tears of emotion, and all of us, in a spontaneous movement; have promised to die beneath our Eagle for the country and Napoleon. I embrace you both with all my heart. [signed] Cardron.' However much Cardron or any of his comrades wanted to believe they could rekindle the glory days once more, it was not to be. The 9è Légère followed their Emperor over the border into Belgium and fought well at Ligny and saw once more the enemiess of France fleeing before their cherished Eagles. On the day of the 18th June, the 9è Légère were engaged in the pursuit of the Prussians towards Wavre when they heard the almighty cannonade coming from Mont Saint Jean. Despite the requests by their corps commander Gérard to march to the sound of guns, Grouchy would not allow them. Only at five o'clock was Gérard finally ordered to push on to rejoin the main body - would it be Marengo all over again?.

With the 9è Légère spearheading Gérard's Corps, the drive was halted at the river Dyle and the bridge at Bierges. Général de Division Hulot led the first battalion forwards but the Prussians were too strong. The water was too deep to outflank the position but some men still tried to swim over and force the flanks -it didn't work. Frantically Gérard himself led the 9è Légère forwards but he was wounded and carried off to the rear. Grouchy put himself in the line of fire and tried desperately to get his men across - still to no avail. Finally Grouchy left Hulot's Division to watch the bridge, while he took the rest of Gérard's Corps to force a crossing over the bridge at Limale. It was all too late, for at ten the next morning the terrible news from the main body reached Grouchy's ears. There would be no second Marengo for the 9è.tried to swim over and force the flanks -it didn't work. Frantically Gérard himself led the 9è Légère forwards but he was wounded and carried off to the rear. Grouchy put himself in the line of fire and tried desperately to get his men across - still to no avail. Finally Grouchy left Hulot's Division to watch the bridge, while he took the rest of Gérard's Corps to force a crossing over the bridge at Limale. It was all too late, for at ten the next morning the terrible news from the main body reached Grouchy's ears. There would be no second Marengo for the 9è.

Again the army fell back towards Paris in disarray, furiously pursued by the Prussians. On the 2nd of July 1815, the 9è Légère fought its last action outside Paris at Issy. The Prussians were held at bay, sous-lieutenant Deslon being the last soldier of the 9è Légère to be killed in action. The next day, the convention of St Cloud was signed and the French army retreated beyond the Loire, where on the second return of the Bourbons, the Imperial army was completely broken. On the 15th September the regiment that had begun one September morning 31 years before, was finally disbanded. The men were ordered to return to their Departements of origin where they would be formed into Légions with no link to either Revolution or Emperor.

As an epitath to the continuity that flowed from the days of de Barroussel, through the madness of the Terror into the glory days of the Empire and final collapse, we see the name of Capitaine Pierre Gros on the register of those officers now put on half pay and discarded. Gros' father had joined the Chasseurs des Cévennes on the 24th September 1784, its first day of existence. As an ex-soldier and a tough old boot at that, Gros was just the kind of man that de Barroussel and de Villionne were looking for in their new battalion. They signed Gros up with a good bounty and promoted him to sergent that same day. Gros though had a big family to look after and needed every denier he could get. Gros' one year old son was therefore made an enfant de troupe, normally a position reserved for orphans. Over thirty summers later, that infant finally laid his sword to rest.

More Spotlight on L'incomparable 9e Leger

|

Between the years 1792-1815 the 9è légère fought in over thirty battles, a blaze of smaller combats, sieges and an innumerable number of outpost skirmishes. As one of the most decorated units in the history of the French army, their deeds, nearly 200 years after their disbanding, still excite the imagination of all that come into contact with their memory . . .

Between the years 1792-1815 the 9è légère fought in over thirty battles, a blaze of smaller combats, sieges and an innumerable number of outpost skirmishes. As one of the most decorated units in the history of the French army, their deeds, nearly 200 years after their disbanding, still excite the imagination of all that come into contact with their memory . . .

De Barrousel's next task was to fill the ranks with eager young men who would serve with the discipline and energy needed by light troops. This was no easy task in a country at peace with its neighbours and where military service was unpopular with a reputation for brutality and bad pay. Unwilling to fill his battalion with vagabonds, drunkards and social misfits, de Barroussel targeted local youths with promises of adventure and backed up his sweet words by paying them a substantial, over-the-odds bounty on their enlistment. This practise soon caught the attention of the financiers in Paris and several warning shots were fired down to de Barroussel - it was the Kings money he was throwing around - not his own! However, de Barroussel's work was largely done: He had a corps of experience officers, good sous-officiers and fit, developing, young lads.

De Barrousel's next task was to fill the ranks with eager young men who would serve with the discipline and energy needed by light troops. This was no easy task in a country at peace with its neighbours and where military service was unpopular with a reputation for brutality and bad pay. Unwilling to fill his battalion with vagabonds, drunkards and social misfits, de Barroussel targeted local youths with promises of adventure and backed up his sweet words by paying them a substantial, over-the-odds bounty on their enlistment. This practise soon caught the attention of the financiers in Paris and several warning shots were fired down to de Barroussel - it was the Kings money he was throwing around - not his own! However, de Barroussel's work was largely done: He had a corps of experience officers, good sous-officiers and fit, developing, young lads.

In 1788 the light arm of the French army was reorganised yet again and Toulongeon's regiment was split in two. De Barroussel took charge of the infantry [which retained the Cévennes title] while Toulongeon took the Chasseurs à Cheval to form the Bretagne régiment. For the next four years, in the lead up to a new war with Austria, massive changes occurred in both the military and social fabrics of France, all of which affected the Cévennes battalion greatly. Although the French Revolution occurred in 1789, it took until January 1791 for the biggest reforms to hit de Barroussel's men. Considering that provincial titles were too feudalistic in their nature, the chasseurs des Cévennes was re-titled the 9è bataillon des chasseurs a pied. A new set of drill regulations was introduced and finally, to cap the spirit of change - the ageing de Barroussel unexpectedly died.

In 1788 the light arm of the French army was reorganised yet again and Toulongeon's regiment was split in two. De Barroussel took charge of the infantry [which retained the Cévennes title] while Toulongeon took the Chasseurs à Cheval to form the Bretagne régiment. For the next four years, in the lead up to a new war with Austria, massive changes occurred in both the military and social fabrics of France, all of which affected the Cévennes battalion greatly. Although the French Revolution occurred in 1789, it took until January 1791 for the biggest reforms to hit de Barroussel's men. Considering that provincial titles were too feudalistic in their nature, the chasseurs des Cévennes was re-titled the 9è bataillon des chasseurs a pied. A new set of drill regulations was introduced and finally, to cap the spirit of change - the ageing de Barroussel unexpectedly died.

Yet again another outsider was brought in to command the 9è, which was rapidly filling its ranks as it moved up to a war footing. The 54 year old de Peudemar at least stayed the course and when the French National Assembly at last declared war in the April of 1792, he led the 9è to the front for the first time. Serving in the Armée des Ardennes under Général Lafayette, the 9è did not get off to such a good start. First engaged around Philippeville on the 23rd of May, after two hours skirmishing de Peudemar was killed and the battalion fell back to reorganise itself.

Yet again another outsider was brought in to command the 9è, which was rapidly filling its ranks as it moved up to a war footing. The 54 year old de Peudemar at least stayed the course and when the French National Assembly at last declared war in the April of 1792, he led the 9è to the front for the first time. Serving in the Armée des Ardennes under Général Lafayette, the 9è did not get off to such a good start. First engaged around Philippeville on the 23rd of May, after two hours skirmishing de Peudemar was killed and the battalion fell back to reorganise itself.

It was here that they received an unexpected visitor in the guise of their ex-lieutenant-colonel, the émigré Segond. Somehow Segond had managed to find a place on the staff of the commander of the Armée du Nord. Général Dumouriez had planned to turn his army on Paris, but when that plan failed miserably, he decided to jump ship over to the Austrians. Dumouriez plotted to steal the army's treasury to retire in luxury with, but needed some accomplices - his new friend Segond went to find these would be deserters in his old unit - the 9è.

It was here that they received an unexpected visitor in the guise of their ex-lieutenant-colonel, the émigré Segond. Somehow Segond had managed to find a place on the staff of the commander of the Armée du Nord. Général Dumouriez had planned to turn his army on Paris, but when that plan failed miserably, he decided to jump ship over to the Austrians. Dumouriez plotted to steal the army's treasury to retire in luxury with, but needed some accomplices - his new friend Segond went to find these would be deserters in his old unit - the 9è.

While fighting ebbed and flowed all along the border of the German states, in Italy the young Général Bonaparte waged a successful campaign that saw the Austrians pushed out of Italy into Austrian itself. This drive led to the end of the war in 1797. At this time Eirisch was replaced as commander by the promising aide de camp of Marceau, [who had been killed the previous September] Auguste Cafferelli du Falga. Under his command, the 9è Légère marched off towards the coast to make up part of the planned invasion force going to England. En-route, the demi-brigade was redirected to Paris where it would remain in garrison for nearly two years.

While fighting ebbed and flowed all along the border of the German states, in Italy the young Général Bonaparte waged a successful campaign that saw the Austrians pushed out of Italy into Austrian itself. This drive led to the end of the war in 1797. At this time Eirisch was replaced as commander by the promising aide de camp of Marceau, [who had been killed the previous September] Auguste Cafferelli du Falga. Under his command, the 9è Légère marched off towards the coast to make up part of the planned invasion force going to England. En-route, the demi-brigade was redirected to Paris where it would remain in garrison for nearly two years.

The Battle Marengo [14th June 1800] is remembered mainly because it gave Bonaparte the victory which cemented his political power and opened the door to him placing the crown of France on his head. However he came very, very close to losing everything at Marengo. His army was exhausted and almost out of ammunition, his Grenadiers à Pied had been shattered; all over the field his men were in retreat while the Austrians advanced to mop up the last remnants of his reputation. However, before the sun set, victory was to side with the French.

The Battle Marengo [14th June 1800] is remembered mainly because it gave Bonaparte the victory which cemented his political power and opened the door to him placing the crown of France on his head. However he came very, very close to losing everything at Marengo. His army was exhausted and almost out of ammunition, his Grenadiers à Pied had been shattered; all over the field his men were in retreat while the Austrians advanced to mop up the last remnants of his reputation. However, before the sun set, victory was to side with the French.

At just ten paces, the 9è Légère took the Grenadier's final volley in which Général Desaix was killed instantly. The momentum of the charge could not be halted though and when the two adversaries clashed, Général Victor remembered that 'the clash was terrible.' Simultaneously, Général Kellermann led a rag bag assortment of Heavies and Dragoons into the rear of the Austrian troops. Assailed by the bayonets of the 9è Légère from the front and cut down by the cavalry from the rear, the Austrians, including their chief of Staff GM Zach, laid down their arms in surrender. This was by no means the end of the battle, only the turning of the tide. At one in the morning the guns finally fell quiet and the enormous losses sustained were counted for the first time. The 9è Légère lost over 300 men killed or maimed that single evening. For their troubles, a grateful Bonaparte dubbed them simply: L'INCOMPARABLE.

At just ten paces, the 9è Légère took the Grenadier's final volley in which Général Desaix was killed instantly. The momentum of the charge could not be halted though and when the two adversaries clashed, Général Victor remembered that 'the clash was terrible.' Simultaneously, Général Kellermann led a rag bag assortment of Heavies and Dragoons into the rear of the Austrian troops. Assailed by the bayonets of the 9è Légère from the front and cut down by the cavalry from the rear, the Austrians, including their chief of Staff GM Zach, laid down their arms in surrender. This was by no means the end of the battle, only the turning of the tide. At one in the morning the guns finally fell quiet and the enormous losses sustained were counted for the first time. The 9è Légère lost over 300 men killed or maimed that single evening. For their troubles, a grateful Bonaparte dubbed them simply: L'INCOMPARABLE.

After reforming, Colonel Meunier led the same battalion in a bayonet charge which pushed back the giants of the Russian Imperial Guard in disorder. That day [14th June 1807] being the 7th anniversary of Marengo, the 9è Léger lived up to their reputation: Napoleon awarded them 36 croix d'honneur.

Then it was off to Spain, where the regiment would serve until 1814. Again the names of battles reel off: Espinosa; Somo-Sierra; Uclès; Médellin; Talavera; Chiclana; Fuentès-de-Onoro; Vittoria; Laon. and finally back over the border at Toulouse. Spain was a campaign marked with bitter fighting and attrocities by and against the local population. However a healthy respect was shown for the British soldiers they fought against; a respect they returned in kind.

After reforming, Colonel Meunier led the same battalion in a bayonet charge which pushed back the giants of the Russian Imperial Guard in disorder. That day [14th June 1807] being the 7th anniversary of Marengo, the 9è Léger lived up to their reputation: Napoleon awarded them 36 croix d'honneur.

Then it was off to Spain, where the regiment would serve until 1814. Again the names of battles reel off: Espinosa; Somo-Sierra; Uclès; Médellin; Talavera; Chiclana; Fuentès-de-Onoro; Vittoria; Laon. and finally back over the border at Toulouse. Spain was a campaign marked with bitter fighting and attrocities by and against the local population. However a healthy respect was shown for the British soldiers they fought against; a respect they returned in kind.