The Battle of Magnano

5th April 1799

A Forgotten Austrian Victory

of 200 Years Ago

by Mag. Herbert Zima, Austria

(Translation Bernhard Voykowitsch, Austria

assisted by Neil Clifford, UK)

| |

Christopher Duffy's book Eagles over the Alps is one of the outstanding publications of Napoleonic military history of 1999. It is the first detailed coverage of Suvorov's famous victories in Italy 1799 in the English language and has filled a long felt void. Given the tremendous number of events to cover, Duffy justifiably concentrates on describing the events of the crossing of the Adda, the battles of the Trebbia and of Novi and the fighting in the Swiss Alps. However the events before Suvorov entered the stage and after he had left it are not as comprehensively covered. This article aims to complete the history of the 1799 campaign in Italy at its start when the Austrian "Army of Italy" rebuilt from its 1796-97 defeats and under an interim commander achieved a valuable but forgotten victory. In the spring of 1799 began the second round in the life-and-death struggle between Europe's conservative powers and revolutionary France. The first round 1792-1797 had ended with a clear French victory. In 1795 Prussia and Spain had left the First Coalition and had signed separate peace treaties. In 1797 Austria was forced out of the war by Bonaparte's victories in Italy which threatened the very existence of the monarchy. At Campo Formido a peace treaty between Austria and the French Republic was signed which must be regarded as a truce rather than a lasting treaty. At a congress in Rastatt a peace treaty between France and the German Empire was negotiated. Now, the 'Directoire', the French government of the time could dare to send Bonaparte with an army to Egypt in order to threaten the sole enemy left - Britain - at a vulnerable point with its colonial empire in India. In their turn the British, who had gained some respite with Nelson's naval victory at Aboukir, busily tried to create a new coalition by promising considerable subsidies. These efforts were successful; at first Naples and the Ottoman Empire, and then Austria and Russia joined the new coalition. The Neapolitans struck in the late autumn of 1798 - too early. They were decisively defeated. It didn't help that they were commanded by the Austrian General Mack (of Ulm 1805 infamy). King Ferdinand of Naples' saying about his army explains the reasons of defeat to the point: "No matter if one dresses them in red or green coats, they always run away." This explains why the 38,000 men strong Neapolitan army could be defeated by some 15,000 French under Championnet. In Naples the Parthenopean Republic, another French satellite state, was proclaimed. Mack had to flee to the French camp such was the Neapolitan rage about his capitulation. The General Strategic SituationThe Austrian preparations for war and the entry of Russian troops into Austria (the Russians crossed the frontier already in December 1798 and then went into winter quarters near St. Poelten) had not gone unnoticed by the French. The French envoys at the congress of Rastatt protested against this breach of neutrality; but in vain. Therefore in March 1799 the French Republic initiated hostilities in all the three main theatres of the war: Germany, Switzerland and Italy (in the summer of 1799 the Netherlands would also become a theatre of the war when a British-Russian expeditionary force landed there). The French attacked in order to prevent the arrival of the Russians. Yet their attacks were not co-ordinated. At first Jourdan crossed the Rhine on 1st March 1799. (He was soon to be defeated on the 23rd and 25th March by Archduke Charles at Ostrach and Stockach.) Then Massena struck in Switzerland, occupied Sargans 6th March 1799 and the following day captured an Austrian force under Auffenberg at Chur. Only on 12th March did France formally declare war on the Emperor and the Grand Duke of Tuscany. In Italy hostilities commenced on 24th March when the French under Schérer crossed the Mincio. The Opposing Forces in ItalyThe Austrians stood with about 59,000 men between the rivers Adige and the Tagliamento. The two divisions of Zoph and Ott with another 25,000 men were still on the march and meant that the Austrian Army of Italy could dispose some 68,613 infantry, 11,919 cavalry, 3,376 artillery and other specialist troops; a total of 84,000. The artillery was made up of battalion guns (2 three pounders per battalion) and 173 reserve guns. In addition there was a siege artillery train of 80 guns in Palmanuova. On Lake Garda both sides each had a flotilla of gunboats. The Austrians had 40 such vessels which were armed with at total of 300 guns and manned by 2,000 men. Of interest here is what FML Stutterheim (an eyewitness and author of the Austrian history of the 1799 campaign) has to say about Austrian infantry tactics: "Here I must mention that from unhappy experiences in the past campaigns our infantry had learned the art to fight in open lines supported by small ranged masses." The Austrian headquarters was located in Padua. FML Baron Kray (the senior divisional commander) was appointed temporary commander-in-chief FML because the designated commander-in-chief GdK Melas had not yet arrived with the army. Melas had been chosen to succeed the talented FZM Frederick of Orange who had died suddenly in January 1799; he was only 26 years old. Melas had refused to take over command due to ill health but had been appointed anyway. He was allowed to travel to the army in a number of conveniently short stages. Paul Kray Freiherr von Krayova and Topolya had been born on 5th February 1735 in Kaesmark, Hungary, the son of an army captain. 1751 he entered service in IR 31 as a cadet and fought during the Seven Years War where was severely wounded in the battle of Liegnitz 1780. He was appointed Major in 1778 and Lieutenant-Colonel with GzIR 2 in 1782. In 1784 he put down a peasant revolt in Transylvania. He became Colonel of GzIR 16 in 1785 and during the 1788-1790 Turkish War he distinguished himself by the covering of the Transylvanian frontier and the taking of Krajova. For this he was promoted Major-General and received the Knight's Cross of the MTO. In 1791 he was pensioned off at his own request. In 1793, aged 58 and very much against his will, he was reactivated upon the special wish of the Austrian commander in chief in the Netherlands, FM Prince Josias von Sachsen-Coburg. As commander of the advance guard he distinguished himself at Orchies, Marchiennes and Famars in 1793, at Menin and Courtray in 1794. In 1795 he was awarded the Commander's Cross of the MTO. He was promoted to FML in 1796 and was with the army in Germany fighting at Wetzlar, Amberg, Wuerzburg and Altenkirchen (where he returned Maurceau's corpse to the French). He was not too successful in the bad year of 1797 and he was transferred to the army in Italy in 1798. He made another request to retire which was denied. After the battle of Magnano, Kray was put in charge of the sieges of Mantua and Peschiera. He joined the field army again and especially proved his worth at the battle of Novi. In 1800 he was appointed commander in chief in Germany. He didn't fare too well during the 1800 spring campaign against Moreau (although the French army was considerably superior in numbers). He finally retired after 48 years of service and died 1804 in Pest (eastern part of Budapest). The Quartermaster General of the Austrian Army of Italy was GM Jean Chasteler Marquis des Courcelles. Members of the staff were Colonel Zach, Lieutenant-Colonel Weyrother and Major Radetzky (commander of the pioneers who was himself to gain renowned victories about 50 years later on the very same terrain). The French Army of Italy boasted a considerable paper strength: 96,023 Frenchmen and 38,925 allied troops, a total of 134,948. Yet of these, 32,000 were in Naples and the Papal State and 14,000 held Corsica, Malta and Corfu. Another division of 6,400 under Gaulthier, upon express orders of the Directory, had invaded Tuscany to chase away the Grand Duke (a member of a Habsburg dynasty) and in order to disarm the small Tuscan army. There were also garrisons to be left in the Piedmontese and Genoese territory. Another weak division of 5,000 under Dessolles had to be detached to Switzerland. Thus French forces in Italy were dispersed and the Directory had utterly violated the principle of concentration of forces. This is the reason why the French main field force between the rivers Mincio and the Adige was a little inferior in numbers to the opposing Austrians. The French Commander-in-chief was Schérer (until recently, the Minister of War). The 6 divisions of the field army were commanded by Delmas, Serurier, Victor, Grenier, Montrichard and Hatry. Here the proportion of non-French troops was considerably high - more than 10,000 Swiss, Piedmontese, Polish and Italians (Cisalpine Republic). This army strongly differed from the 1796-97 Army of Italy. Bonaparte had taken his crack troops to Egypt and the Army of Italy had been replenished with units from the Army of the Rhine and numerous recruits. The most of the generals also came from other armies notably the Armies of "Sambre-et-Meuse" and the "Rhin-et-Moselle". The Chief-of-staff was GB Musnier and Inspector of the Infantry GD Moreau whom Schérer used as kind of second in command. Bartélemy Louis Joseph Schérer was born near Belfort in 1747, and entered the Austrian army in 1760 as a cadet and served with the artillery during the Seven Years War. He later joined the Dutch army and subsequently left as a Lieutenant-Colonel in 1790 to enter the French army. He was promoted GB in 1793 and served with the Armies of the Rhine, the North and the Sambre-and-Meuse. In 1795 he was appointed commander-in-chief of the Army of Italy and was its leader in the victorious battle of Loano. In 1796 he was appointed Inspector of Cavalry. Between 1797 and 1799 he was Minister of War, and then became supreme commander of the Armies of Italy and Naples. Soult wrote about him: "General Schérer left the war ministry and the scandal, which was the guilt of the members of the government, fell upon him. The spiteful tyranny of the directory had put the army at the mercy of the army suppliers and Schérer had been too weak to resist. Yet the common soldier in his sufferings went that far in his judgement that he accused his direct chief, the minister of war as the one guilty. General Schérer suffered all the bad consequences he would not have deserved and was badly received when he arrived with the field army." The very critical Duchess of Abrantes, the wife of French General Junot (a friend of Napoleon) writes in her memoirs that Schérer had been denounced and left his widow and children without means of support when he died in 1804. The Rival PlansThe Austrian Court War Council had drafted a detailed plan of operations for the Austrian Army of Italy with which the new Quartermaster-General of the army, GM Marquess Chasteler, arrived on the 21st March 1799. This plan was muddled and left the leaders of the army little room for initiatives of their own. Clausewitz was justified to ridicule this plan in his history of the war. On the other hand the Court War Council expected the army to operate on the offensive: "The Army of Italy shall with all its force advance by Brescia and Bergamo to the Adda; take the rear of the valleys leading to the Tyrol, Grisons and the Valtelfin. The first step shall be the crossing of the Tartaro and the Tion. With this operation the attack of Peschiera is connected. The bridges of Goito and Vallegio shall be overwhelmed and then army shall cross the Mincio. At Goito shall remain a considerable corps in order to observe Mantua and to secure communications. Then Peschiera shall be besieged, the army shall occupy Lonato and advance to the Chiesa while General St.Julien has to attack the enemy in the Chiesa valley. The further operation shall go until Brescia and Crema. From Brescia a corps shall be detached by Palazzuolo along the Oglio to Edolo and the Tonale pass, a second corps by Bergamo and Lecco along Lake Como and the Adda into the Valtellin and to Chiaverina. Where the enemy is found in concentration a main battle is to be given. Along this plan the Tyrol can be freed without mountain warfare." It was also the obvious (and quite sound) intention of the Court War Council to await the arrival of both commanders in chief (Melas and Suvorov) as well as the arrival of the 25,000 Russians before this plan was to be executed. Although he had no explicit orders to do so, Kray decided to go to the offensive. On 25th March he wrote to the President of the Court War Council that it seemed him to be irresponsible to keep the forces in Italy in an inactive concentration and to leave the enemy the time to execute his purposes elsewhere. The Austrian progress in Italy could thwart the enemy main plan and could force him to withdraw from the Tirol and Grisons. Therefore in two days he would attack the French and he promised to defeat the enemy still on the near side of the Mincio. Likewise, the Directory, the French government, in its instruction for the army commanders had ordered the French Armée d'Italie onto the offensive: "The Army of Italy which consists of about 50,000 men along the rivers Adige and the Po without taking into account the Cisalpine, Ligurian, Polish and Piedmontese troops - will operate on her left wing. The mass of the army will cross the Adige at Verona, will occupy this town and then will push the enemy behind the Brenta and the Piave. ..." The army further should send detached corps to its flanks to Bozen (Bolzano) and Brixen (Bressanone) in order to establish communications with the Army of Helvetia. Finally Tuscany should be invaded and the Cisalpine and the Piedmont Republics should be covered. The Combats of 26th March 1799The determination of both army commanders to go to the offensive had to lead to a clash. The Austrians had covered their northern flank by an entrenched camp comprising 14 redoubts and 4 fléches in the narrow strip of land between Lake Garda and the Adige. This was rather weakly occupied by the brigade of Gottesheim reinforced by Elsnitz's brigade (7,130 infantry and 702 cavalry).

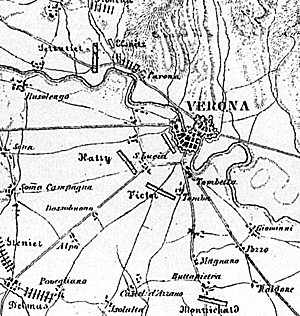

At Pol two pontoon bridges had been built across the Adige but the entrenchments had not yet been completed. Gottesheim is an interesting person: he was a French émigré, an Alsatian, who at the head of the Saxe Hussars had changed over to the Allies and then entered Austrian service. Of the Austrians, the divisions of Kaim and Hohenzollern (formerly Kray) with a little over 20,000 men stood near Verona. On the southern wing at Bevilacqua was the Austrian headquarters and the divisions of Frelich and Mercandin with also some 20,000 men. They would confront the right flank of any enemy advance to Verona. According to the memoirs of Radetzky this plan had been suggested by Colonel Zach upon the report of a spy. Brigade Klenau (4,500) had been sent south to cover the Austrian left wing and therefore was detached from the fighting to come. The divisions of Zoph and Ott had not yet arrived and only the brigade of St.Julien had been ordered to march through the Brenta valley to Trient (Trento) in order to secure communications with the Tirol. Deducting the detachments - Klenau's brigade and some additional 3 battalions - and adding the fortress garrisons, there remained 55 battalions, 10 Jaeger companies and 36 squadrons. Adding in the artillery brought the total to almost 55,000 men.

As opposed to the Austrians, the French had massed their forces on the their northern wing. Three full divisions - Serurier, Delmas and Grenier with 23,000 men would attack the position of Pastrengo and then cross the Adige in order to advance on the eastern side and push back the Austrians from Verona. Schérer thought that the Austrians were massed at Rivoli as in 1796/97. He therefore intended to attack Rivoli before crossing the Adige. Against Verona and under the overall command of Moreau there stood the divisions of Victor and Hatry with 15,000 men while in the south Montrichard with his 9,000 strong division would observe Legnago and await the order to cross the Adige. The French totalled some 46,000 to 47,000 men. Other sources give the French at 43,000. The French commander-in-chief was with the three divisions of the left wing. Both commanders were unaware of enemy intentions and both had massed their main forces on their respective left wing. When the French attacked at 3 o'clock on 26th March the Austrian position at Pastrengo, with its incomplete entrenchments, was only weakly held. The Ist and IInd battalions of IR 53 Jellacic held the entrenchments and the heights south of Pol and near Bussolengo. The Ist and IInd battalions of IR 59 Jordis stood to the west, the Oguliner Grenz battalion on the hills of Calmasino and the Warasdiner-Kreuzer in and near Pastrengo. Outposts were manned by 5 companies d'Aspre Jaeger and 2 divisions of HR5. In addition FML Kaim had sent IR 26 Schroeder and a cavalry battery as reinforcements to Pastrengo. These reinforcements arrived only after the fighting had already started. Schérer advanced Serurier's division on the left French wing through Lazise and Bardolino to Incassi. Delmas' division was in the centre and marched through Caprino, while Grenier was sent through Bussolengo with orders to unite with Delmas. Serurier on the left wing easily pushed back the Oguliner Grenz battalion to Rivoli. Thus the right Austrian flank was wide open. In the centre Delmas had more problems. Only when Grenier, whose division had captured Bussolengo, went into combat could the regiments of Jellacic, Jordis and Schroeder be defeated. The Austrians were able to bring the larger part of their troops back to the eastern bank of the Adige and to dismantle one of their pontoon bridges. The second pontoon bridge fell into the hands of the pursuing French. The Austrians now retreated along the Adige to the south and took up positions first at San Ambrogio and San Pietro then at Parona where they tried to re-establish order. Austrian losses were heavy; 641 dead, 1,379 wounded and 1,516 prisoners (total 3,536 men) and 12 guns. The French also suffered severe losses. The French had forced the crossing of the Adige and nothing now hindered their advance south to Verona. Yet for reasons that cannot be understood the French commander let this opportunity pass. The French maintain that the captured pontoon bridge was damaged by a ferry that the Austrians sent down the Adige and the repair took five hours. In his"Apercu des operations militaires de l'Armée d' ltalie" Schérer has tried to justify his behaviour as follows: "it would have taken more than 5 hours to repair the bridge. The chance to follow the enemy to Verona thus was gone because one cannot take a bastioned town defended by 50,000 men if the garrison closes the gates." If one believes this implausible justification one must ask why Schérer left his own pontoon train at Peschiera. It is even more remarkable when according to French reports at 6 o'clock in the evening GB Musnier, Schérer's chief of staff urged Moreau to renew his attacks in the centre because the commander in chief was advancing from the north against the gates of Verona and was needing support. Michailowski-Danilevski gives a description which is worth considering here: "Some historians say that one of the bridges had been destroyed by the retreating Austrians and that the other bridge had already been taken by the French who also started to cross to the eastern bank. Yet no more than 400 had crossed over it when the big boat that was in the middle of the river (probably deliberately set loose by some Frenchmen) was swept away by the river, destroyed two pontoons and thus cut the connection which only could be restored with great pains after 5 hours. Other historians say that Serurier made it to the left bank of the Adige on this day and came as far as Chiusa and thus had turned the fight wing of the Austrians ..." On the same day combat had also taken place in front of Verona. The Austrians awaited the French attack in three lines. In the first line two battalions IR 36 Fuerstenberg had occupied San Massimo and Santa Lucia and in Tomba was one battalion of IR 14 Klebek. The outposts were manned by 2 companies of Jaegers and some Hussars. The second line was behind Santa Lucia and in front of the Porta Nuova of Verona. It comprised the grenadier battalion Pers and the Ist battalion IR 48. A squadron of HR 5 covered both wings. Behind them in the third line there were 2 battalions of IR 40 Mittrowsky and the IInd Battalion IR 48. In addition 6 squadrons of Levenehr dragoons formed a reserve. At the Porta San Zeno behind San Massimo there were 2 battalions IR 32 Giulay, IIIrd battalion IR 40 Mittrowsky, the grenadier battalion Stentsch and the Karacsay dragoons. In Verona only IIIrd battalions of IRs 48, 53 and 59 and 2 battalions of IR 14 Klebek formed a reserve. The Austrian first line was commanded by GM Lipthay who was at Santa Lucia. The overall command of Austrian troops at Verona had FML Kaim. The French attacked with Victor's division against Santa Lucia, with Hatry's division against San Massimo. San Massimo is approximately 1,200 metres from Verona and Santa Lucia some 1,500 metres south of San Massimo. Both villages were carried by the French attack during which the Polish Legion and the 15th Chasseurs particularly distinguished themselves. Both GM Lipthay and GM Minkwitz were wounded. GM Prince Hohenzollern-Hechingen counter-attacked with 2 battalions and the Levenehr-Dragoons, re-captured Santa Lucia but was again driven out. FML Kaim then lead the second line from the Porta San Zeno against San Massimo. Bitter fighting for the village ensued during which it was taken and lost several times. Finally it remained with the Austrians but FML Kaim was wounded in the process. At 9 o'clock in the evening the fighting ended. The French withdrew from Santa Lucia and on the next day took up positions at Dossobuono. Losses on both sides were considerable with 240 killed, 1,296 wounded and 1,063 missing and captured on the Austrian side; French losses are said to have been higher still. The third area that saw fighting on the 26th March was the area surrounding Legnago. Montrichard had orders to observe Legnago and was to build a bridge further up the river. It seems that Montrichard didn't want to restrict himself to the execution of this order but attempted a serious attack on Legnago. Defeated by the garrison he ordered Vigne's brigade to march on Anghiad while Gardanne's brigade remained in front of Legnago. When FML Kray learned about the French advance he ordered the troops in the camp of Bevilacqua to march to Legnago - a distance of about 10 kms. Reinforced by the fortress garrison he advanced across the Adige. The Austrian attack took place in three columns: The 1st or Left column under GM Lattermann (2 coys Jaeger, Ist battalion IR 28 Frelich, 2 battalions IR 39 Nadasdy, the grenadier battalions Korherr and Mercandin, 2 squadrons HR 8 and 1 pioneer coy) had to advance against Gardanne to San Pietro. The IIIrd battalion IR 45 was sent into the left flank of the 1st Column. The 2nd or Right column under Colonel Marquess Sommariva (IIIrd battalion IR 39, 3 battalions IR 43 Thurn, grenadier battalion Weber) had to advance to Anghiari against Vigne's brigade. The 3rd or Centre column under Colonel Riedt von Callenberg (2 battalions each of IR 45 Lattermann and IR 28 Frelich) marched into the direction of a farm north of San Pietro. Thus Kray had constructed ad-hoc attack formations from the several divisions and the fortress garrison. The assignment of units to brigades and divisions still was not done on a permanent basis by the Austrians and obviously hindered efficient control of battlefield tactical units. The first Austrian column pushed the French back to San Pietro while the centre column went around the French let flank. Gardanne's brigade was forced to retreat but was able to withdraw under the cover of the night. The Austrian right column was delayed by a French battery that was positioned on a dam. Only when the battery had been turned and then taken could Anghiari be stormed. The French fled after GB Vigne was killed. The Austrians lost 81 dead, 586 wounded and 72 prisoners, French losses are given as 2,000. In addition, the Austrians captured 15 artillery pieces. On the 27th March Montrichard managed to re-unite his two battered brigades and withdraw to Isola della Scala. The result of the fighting on the 26th March was a bloody draw. The total loss of the Austrians was 6,695 men and 12 pieces, that of the French was 3,000 killed and dead, 1,500 prisoners and 15 pieces. According to other sources the French lost 4,600 dead and wounded and 900 prisoners, the Austrians 4,520 dead and wounded and 2,631 prisoners. Schérer had won a victory at Pastrengo which, for an unexplained reason, he did not exploit. As the combat of Pastrengo had ended at 8 o'clock in the morning a crossing of the Adige was still possible. In front of Verona the opponents departed without either side gaining a significant advantage. To the south of Verona the French had to accept defeat. A critical survey of the leadership of both armies must come to the conclusion that although Schérer had developed the better plan he lost his nerve at the critical moment. Had he had the moral courage to cross the Adige and to advance with 20,000 men south to Verona he would have encountered only minimal resistance from the battered survivors of Pastrengo and as a last reserve 5 Austrian battalions in Verona. A French success here would have been more than likely. Austrian Quartermaster-General Chasteler has said this expressly: "Had General Schérer exploited the flaws of the first Austrian disposition he would have been able to invade Italy after the combat of Verona because he had 42,000 men against 23,000." Montrichard had ventured too far, he had exceeded his orders and his defeat must be attributed to his own carelessness. As previously mentioned, Kray had wanted to attack only on the next day. His dispositions must be seen in this light. Never-the-less the weak occupation of the position of Pastrengo, the idea of a flanking movement from the relatively distant Legnago in a north-westerly direction and the detaching of Klenau's brigade to the south must be deemed as mistakes. The preference of cordon-like positions and the dispersal of forces (a common mistake made by Austrian generals) was obvious. Yet, as we will see, Kray was to draw the correct conclusions from the events of 26th March. Regrouping of Forces and the Combat at Parona on 30th March 1799

The bloody and pointless fighting on 26th March caused both commanders to reconsider their situation and to change their plans. Kray decided to concentrate his forces at Verona on the eastern side of the Adige and to await the arrival of reinforcements. Zoph's division was to arrive on the 29th March and St.Julien's brigade had been ordered to join from the Tyrol. Only Klenau's brigade was left in its original detached position. The Austrian army would observe the Adige between Verona and Legnago. In the French headquarters Schérer's decision not to cross the Adige on 26th March had found lively resistance. Even on the 27th Moreau had tried to change Schérer's mind - in vain. At a council of war on the 29th in Villafranca the attending French generals reproached their commander-in-chief for having missed such an opportunity. As Kray had concentrated his army at Verona the forcing of the Adige in the north had become impossible. Therefore the French council of war decided to concentrate the French army in front of Verona and to try to cross the Adige down the river near Ronco or Albaredo. Accordingly the French pontoon train was sent to lsola Rizza between Verona and Legnago. Obviously this was to be a repetition of the successful manoeuvre of Arcole in 1796. Yet the French would have to perform a flank march in front of the Austrians at Verona. Therefore Schérer ordered divisions of Victor and Hatry to remain in their positions in order to cover the march of Grenier's and Delmas' divisions coming from the left wing. Serurier's division received orders to distract the enemy's attention by an attack on the eastern side of the Adige. This was a very risky operation because a single division was separated from the army by an impassible obstacle like the Adige. The Austrian battalions of IRs 53 and 59 that had fought at Pastrengo stood near Parona. They were commanded by GM Elsnitz and had been reinforced by IR 14 and 4 squadrons Karaczay dragoons. The Austrians took up positions with the 1st and lInd Battalions IR 59 Jordis between Parona and Arbizzano, Ist and IInd Battalions IR 53 Jellacic to the left in the direction of the Adige, and, on the right, IR 14 Klebek against Nevera. Serurier had Meyer's brigade and the advance guard under General Adjutant Garreau advance through Pescantina while the mass of his division advanced to Piedemont and over the hills to the north. When the French had pushed back the Austrian outposts and were about to attack the Austrian main position, FML Kray arrived in person bringing reinforcements in the form of 7 battalions and 4 squadrons. These were from Frelich's division and consisted of 2 battalions each of the IRs 39 Nadasdy and 43 Thum, the grenadier battalions of Weber, Fiquelmont and Korherr as well as 4 squadrons of the HR 5. The 14 Austrian battalions immediately formed three columns and went onto the attack. The grenadiers relentlessly pushed along the Adige to the French pontoon bridge. Its tows were cut and those French troops that had not yet reached the far side of the river had to surrender. The Austrians lost only 390 men during this brilliant success while the French suffered severe losses; 4 chefs de batallion, 73 officers and 1,100 men were taken prisoners. The total French loss is said to have amounted to 1,700 men. After this setback Schérer withdrew Serurier's division to Bovolone behind the centre of the army. Magnano Part 2: The Battle of 5th April More Magnano

Battle of Magnano 1799: Orders of Battle Battle of Magnano 1799: Large Maps (extremely slow: 496K) Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #49 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 1999 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com |

the Adige near Pol and Pastrengo.

the Adige near Pol and Pastrengo.

Looking upstream on the Adige from the modern bridge at Pol.

Looking upstream on the Adige from the modern bridge at Pol.