Deployment And Plans

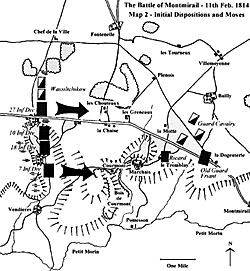

When Sacken arrived on the battlefield he deployed his forces and prepared to attack what he believed to be a weak covering force. He commanded two infantry corps (VI and XI) and a cavalry corps. The 7th and 18th Divisions (of VI Corps) were deployed on either side of L'Epine-aux-Bois with the 10th Division (of XI Corps) on their left.

When Sacken arrived on the battlefield he deployed his forces and prepared to attack what he believed to be a weak covering force. He commanded two infantry corps (VI and XI) and a cavalry corps. The 7th and 18th Divisions (of VI Corps) were deployed on either side of L'Epine-aux-Bois with the 10th Division (of XI Corps) on their left.

The 27th Division (the other division of XI Corps) and the cavalry of Wassiltchikow's corps were posted north of the Chalons to Meaux road. These forces were formed up in two lines in low ground with a grand battery of 36 guns on the high ground behind them. Although this battery looked impressive, because of the state of the ground they were unable to move forward and remained out of range of the French. Another battery stood to the right of the main road with a further one on the extreme left of the Russian line.

Napoleon's deployment very much reflected Sacken's with his cavalry north of the main road and his infantry south of it. Nansouty's Guard Cavalry Divisions covered a line from the village of Bailly in the north to the road near le Tremblay. Guyot's and Laferrierre's were in the front line with Colbert's tired division, which had led the advance, in reserve. In the area of le Tremblay was Ricard's division with Friant's 1st Old Guard Infantry Division in reserve.

Two weak Legere battalions (2/2nd and 7/4th), perhaps not more than 200 men, were placed around Plenois to watch out for the Prussians, and other skirmishers from Ricard's division were deployed on the western edge of the Courmont Wood.

Early Morning

By early morning Sacken had realised that the French had beaten him to Montmirail. However, he did not realise that it was a substantial force that barred his way and surely did not know that Napoleon himself commanded it. He was in communication with Yorck as the Prussian advanced down the Chateau-Thierry road but despite the relatively easy option of travelling across country to join him, seemed obsessed with the idea of fighting his way through to Blucher.

Having deployed his force his plan was to attack south of the road and seize Marchais which he felt was the key to the French position; this attack would be supported by a move along the main road which would take the farm of les Greneaux and threaten the French centre. Sacken seemed to feel that if these attacks were successful, the French, outflanked to the south and threatened by the advancing Prussians from the north, would be forced to withdraw or risk being crushed between the two forces.

Perhaps being more aware of the difficulty of the ground south of the road, Napoleon felt the open ground along the main road and to it's north was the key to the battle. This space gave him the opportunity to use the speed of manoeuvre, of which he was the master, to launch the decisive attack and outmanoeuvre the Russian forces bogged down in the south. However, before he could consider launching such an attack, particularly in the light of the Prussian approach, it was vital that he should have a properly constituted reserve. He was therefore forced to act on the defensive until Michel's 2nd Old Guard Infantry Division (which incidentally contained no Old Guard units) and Defrance's Gardes d'Honneur arrived. This had the advantage of allowing Sacken time to compromise himself in the south before launching the decisive attack.

The Battle

Having deployed, Sacken's troops swung quickly into action; Gen. Heidenreich, who had been ordered to take Marchais, advanced with over 2,000 men made up of the infantry regiments Pskof, Vladimir, Tambov and Kostroma, two companies of the 11th Jägers, the Don Cossacks and 6 light guns. It seems that this attack was supported by the balance of Prince Scherbatov's 7th Div. with the aim of swinging round the captured Marchais and rolling up the French line. At the same time, the advance along the main road was developed; this was generally unopposed and the farm of les Greneaux was occupied and fortified.

Despite his guns being unable to support his attack due to the mud, Heidenreich had successfully driven Ricard's troops out of Marchais by 11 o'clock. The ease with which this was achieved suggests that it was not vigorously contested, perhaps as part of Napoleon's plan of drawing as much of the Russian force south of the road as possible (or perhaps not depending on your viewpoint!) Either way, to ensure that they were unable to exploit this success, Ricard was ordered to counterattack and if unable to retake the village at least to keep the Russians in check.

The rest of the morning and the early afternoon settled into something of a pattern: The Russians, determined to control Marchais, committed more and more troops to achieve this. Napoleon, restricted by his shortage of troops was able to conduct only localised counterattacks to maintain his position, draw as many Russian troops south of the road as possible and buy time for the arrival of reinforcements. There seems little doubt that Napoleon's tactics proved more successful: Marchais changed hands at least three times, Sacken was forced to weaken his centre (where Napoleon planned to attack) to secure the village and by the time that Ricard's infantry, which by this time had been reinforced by a battalion of the Old Guard and the arrival of some more artillery, had been forced back to le Tremblay, Napoleon's much needed reinforcements were in sight. The fighting around Marchais was clearly quite fierce as statistics testify: Around 7,000 Russians got drawn into the fighting around this small village and at one point they had managed to advance from it and gain a foothold in le Tremblay before being pushed out again. Ricard's small division lost 50% casualties in the battle.

It was some time around 2pm that Michel's 2nd Old Guard Division arrived. Although consisting of only six weak battalions (the Fusilier-Grenadiers and -Chasseurs had been left to garrison Sezanne), along with the arrival of Defrance's division of Gardes d'Honneur (which included the 10th Hussars) Napoleon was now able to move onto the offensive.

Michel's troops, under command of Marshal Mortier, were to move to the north to ensure the arrival of the Prussians did not interfere with Napoleon's planned destruction of Sacken's corps. At this stage Yorck was still advancing rather cautiously to aid his threatened ally and was still not in a position to influence proceedings on the battlefield. Only Katzeler's cavalry had arrived and was deployed to keep communications open between the two allied forces; it thus took little or no part in the fighting.

Despite the arrival of Michel, Napoleon's position was still not secure. If Yorck was to arrive in strength then Michel's tired division was barely strong enough to be able to offer a concerted resistance. Ricard's division was fighting valiantly but having been committed for several hours and having suffered significant casualties it was relying on the support of the Old Guard battalion and was in no position to make a telling contribution to an offensive. This only left Friant's Old Guard Division and the Guard cavalry to deliver the decisive blow and if this was the ideal force, it's launch would leave Napoleon with no reserve at all; not a situation even he could consider with equanimity.

Even so, with the Russians potentially fatally compromised in the south and the Prussians so far failing to make a substantial appearance, now was the opportunity Napoleon had been waiting for. It seems that he was also helped by the fact that as the Prussians drew slowly closer, Sacken further weakened his centre by sending troops to the north to secure the communications between them.

Bravest of the Brave

Napoleon chose Ney to lead the main assault which was to comprise of four battalions of the Old Guard with two more advancing some distance behind to act as a reserve. 30 guns of the Guard Artillery supported the attack and the Gardes d'Honneur covered the right flank, ready to counter any move of the Russian cavalry. Finally, the Guard cavalry was positioned to be able to exploit any gap caused in the Russian line.

Using the main road as an axis Ney led the Old Guard forward. Despite the strength of their position, it seems that the Russians entrenched in les Greneaux were put to flight by the very appearance of these famous troops. Certainly no serious resistance was put up and a number of guns were abandoned.

Having breached the Russian front line the Old Guard were counterattacked by some of the Russian cavalry. However, deploying calmly into square these were easily thrown back and the advance resumed. Ney continued to la Meuliere where he was in a position to attack la Haute Epine and from where he outflanked those Russian troops south of the road.

Sacken realised that he was in a precarious position; his forces were in danger of being cut in two and his right flank cut off and isolated. He immediately sent elements of Lieven's XI Corps forward in an effort to hold the French attack and to buy time to extract his forces committed south of the road. Unfortunately for him this counterattack was repulsed by the Old Guard. As the seriousness of the position became clear he determined to move north to close up on the advancing Prussians. Given the extent to which his troops were committed south of the main road, particularly those as far forward as Marchais, this was obviously going to be a manoeuvre fraught with danger, moving as they would have to across the front of the French.

Crucial Time

![]() It was at this crucial time, with the Russian counterattack defeated and the movement of troops to the north, that Napoleon launched the Guard cavalry. This attack was spearheaded by Letort's Guard Dragoons led by Dautencourt. Moving down the line of the main road they swung south of la Chaise and charged into the Russian troops moving back from the area of Marchais. A number of squares were broken and the withdrawing units thrown into confusion. These fugitives were then charged by the Guard Grenadiers and Marmalukes with devastating results. The Dragoons rallied on the high ground overlooking L'Epine aux Bois. Led by Guyot, the four Service Squadrons were then launched down the road pursuing the survivors to La Bord Wood, 500 meters beyond la Haute Epine.

It was at this crucial time, with the Russian counterattack defeated and the movement of troops to the north, that Napoleon launched the Guard cavalry. This attack was spearheaded by Letort's Guard Dragoons led by Dautencourt. Moving down the line of the main road they swung south of la Chaise and charged into the Russian troops moving back from the area of Marchais. A number of squares were broken and the withdrawing units thrown into confusion. These fugitives were then charged by the Guard Grenadiers and Marmalukes with devastating results. The Dragoons rallied on the high ground overlooking L'Epine aux Bois. Led by Guyot, the four Service Squadrons were then launched down the road pursuing the survivors to La Bord Wood, 500 meters beyond la Haute Epine.

It was only now, with the Russians facing disaster, that the Prussians started to make a significant appearance. At 3.00pm the 1st Brigade (Pirch) passed through Fontenelle and turned towards les Tourneux. However, having deployed, this brigade waited until the 7th Brigade (Horn) had formed a supporting second line before making any move to take some of the pressure from their Russian allies. Each brigade had only a light battery to support them as the heavy artillery had been left at Chateau Thierry. It seems that they were also supported by a Russian battery on the right of their line.

The 1st Brigade advanced on the village of Bailly once the Plenois Wood had been cleared of French skirmishers. The artillery was dragged forward with considerable difficulty to support the advance. Having occupied Bailly they were immediately counterattacked by Michel's division and thrown out again. Ordered to retake the village the attack was led by Pirch himself and comprised of the whole of the 1st Brigade and the 15th Silesian Landwehr of the 7th Brigade. However, the attack was met with heavy musket and canister fire from the village and outflanked by a strong force of French skirmishers; the assault faltered and fell back, Pirch was wounded.

The French now attacked the Prussian right and they were forced to withdraw towards the second line between Fontenelle and les Tourneux. Although the situation was stabilised the Prussians failed to mount another attack before orders were given to withdraw. Even now Michel's troops attacked the rearguard and hurried them off the field.

The French now attacked the Prussian right and they were forced to withdraw towards the second line between Fontenelle and les Tourneux. Although the situation was stabilised the Prussians failed to mount another attack before orders were given to withdraw. Even now Michel's troops attacked the rearguard and hurried them off the field.

With the Guard cavalry sweeping the battlefield along the main road and the Prussians failing dismally to influence events, Napoleon's final move was to seal the fate of Marchais. Whilst Ricard was ordered to make one final effort with his exhausted conscripts by attacking from le Tremblaye, the last two available battalions of Old Guard were to launch a simultaneous assault from the north of the village. Already fearful for the security of their withdrawal route, and facing a co-ordinated attack from different directions, the remaining defenders of the village offered little resistance and tried to make good their escape about 5pm. Being forced to withdraw past the victorious French cavalry this was a perilous operation. Charged by the Gardes d'Honneur those that had held out the longest were nearly all killed or captured. The brigades of Dieterich and Blagovenzenko were both virtually wiped out.

Sacken's Last Card

Sacken had one last card to play to avoid the total destruction of his corps: He now threw his cavalry at the French in order to clear his withdrawal route to the north where he could combine with Yorck's Prussians. Although they had successfully routed the Russian forces in the centre and south the Guard cavalry was tired and inevitably somewhat disordered by it's exertions. It was therefore not in a position to offer significant opposition to the still powerful Russian cavalry and was steadily pushed back.

The actions of their cavalry had given the shattered Russian infantry the opportunity they needed to finally break clean and make their escape. They were aided by the gathering darkness which eventually brought the fighting to an end. Covered by Wassilchikow's cavalry the infantry and artillery straggled north to the comparative security of the Prussian forces who had been able to extract themselves in reasonable order. As it was a number of damaged guns had to be abandoned and many others were only saved by using cavalry horses to supplement those of the train.

The darkness and the terrible condition of the tracks the Russians were forced to take made the withdrawal a nightmare, but at least the same conditions spared them from what could have been a devastating pursuit. Even if the conditions had been more conducive, the French were too exhausted to pursue their beaten enemy. Napoleon spent the night in the farm of les Greneaux and the pursuit was only started at 9.00am the next day.

Aftermath

There is no doubt that the battle of Montmirail had been a decisive French victory. However, equally there can be little doubt that it was not quite as decisive as Napoleon would have hoped; he was surely trying to take Sacken out of the equation all together and the fact that he almost achieved it can have been of little comfort to him.

Russian losses are given between 2 and 3000 casualties, 800 to 1000 prisoners and up to 13 guns. Despite their rather cautious and limited intervention the Prussians suffered quite severely; around 1000 of their 4 to 5000 men were casualties. The French lost 2000 men, 900 of which were Ricard's men, a testimony to the fighting spirit of the Marie Louises. In his Second Bulletin from the front Napoleon wrote: "Never did our troops display more ardour. The enemy, everywhere broken, is completely routed"

On the 12th the pursuit began in earnest in an effort to finish off the job of the day before. As the least disorganised of the two Allied corps, the Prussians provided the rear guard. They took up a position on the Caqueret hills about two thirds of the way to Chateau Thierry. Fresh from their convincing victory of the previous day the Guard infantry and cavalry soon pushed this force off their positions and into a precipitate withdrawal towards Chateau Thierry.

The retreat now became a running fight as the Prussians and Russians desperately attempted to escape north across the Marne. Despite the attempts of Yorck's previously uncommitted 8th Brigade (that of Prince Wilhelm), the French proved unstoppable and the Allies only narrowly escaped. However, the bill was heavy; the Prussians lost 1250 men, 6 guns and part of their baggage and Sacken lost a further 1500 men, 3 guns and nearly all his baggage. The French loss had not been more than 600.

Having ordered Mortier to continue to press Sacken and Yorck, Napoleon now planned to move against Schwarzenberg on the Seine. However, early in the morning of the 14th he heard that Blucher was advancing against the weak forces he had left with Marmont. He was therefore compelled to move in Marmont's support before turning his attention south. Moving quickly to join this Marshal Napoleon launched a furious assault on the Prussian at Vauchamps which took them completely by surprise.

Making the most of his rarely found superiority in cavalry Napoleon threw the Prussians back to Etoges where the rearguard was surprised and slaughtered. The retreat did not end until Chalons. By this time the corps of Kleist and Kapzewitch had lost about 6000 men and 16 guns, Napoleon's loss was comparatively insignificant. From the 10th to the 15th of February Blucher had lost in the region of 16,000 men out of a total of 56,000. The French had lost around 4,000.

Despite this considerable achievement Napoleon had no time to gloat: In the short time he had taken to deal this significant blow against Blucher, his forces in the south had been pushed back by Schwarzenberg's overwhelming forces. With Fontainebleau directly threatened by Cossacks Napoleon was forced to hurry towards the Seine to deal with this new threat. Despite his successes in the following days the need to be at two fronts at the same time and the continuous attrition of his army ultimately resulted in his defeat and abdication.

Sources

Most of the sources used for this narrative and listed below are widely available through the advertisers in this magazine. Despite being a relatively small battle the various accounts do contradict each other considerably. This is particularly true, perhaps understandably, between accounts of each of the respective participants. Inevitably, the French portray a glorious victory whilst the Russians describe an equally glorious defeat in the face of overwhelming numbers. Prussian accounts tend to be rather more balanced in describing their own performance and casualties. The Eagles, Empires and Lions articles are based on the most contemporary sources and give each of the three participants' account of the battle. However, despite this being an interesting approach, it does rather confuse the overall picture as various formations appear at different parts of the battlefield at the same time!

The most balanced account of the campaign, although without a very detailed account of the battle itself, is to be found in Operations of the Allied Armies 1813-1814 by Lord Burghersh. Given the contradictions between the various accounts of the battle I have based my own account on those phases where the sources are in agreement where this is not possible on what I interpret as the most likely or logical.

Bibliography

Empires, Eagles and Lions Magazine, Vols 7 to 10.

Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon.

Houssaye, 1814 France.

Mikhailofsky-Danielofsky, History of the Campaign in France in the Year 1814.

Lord Burghersh, The Operations of the Allied Armies in 1813 and 1814.

Petre, Napoleon at Bay.

Baron Fain, Memoirs of the Invasion of France 1814.

Count Yorck von Wartenberg, Napoleon as a General.

Tranie and Carmigniani, Napoleon - 1814 La Campagne de France.

Philippart, The Campaign in Germany and France.

Lachouque, The Anatomy of Glory.

More Monmirail

-

Background and Prelude to Battle

Large Photographs of the Battlefield (extremely slow: 338K)

Orders of Battle

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #36

Back to First Empire List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by First Empire.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com