Background

Background

After it's catastrophic defeat at Leipzig in October 1813 the French army's retreat did not end until it had finally left the occupied territories of Germany and crossed it's own frontiers back into France itself. Those remaining with the Eagles were a shadow of the rebuilt Grande Armée of 1813, perhaps only 70,000 men fit for duty. Behind them, their former allies and comrades-in-arms had each made their own arrangements with the victorious Allies on the best conditions they could get: Almost all included the requirement to contribute troops to the impending invasion of France.

As his Marshals attempted to hold the Allies on the French frontiers with the miserable resources that were available, once again Napoleon was making superhuman efforts to raise both morale and troops in Paris. That he was able to devote so much time to this was due to the failure of the Allies to effectively follow up their success at the Battle of the Nations. It was therefore not until the turn of the New Year that the two main Allied armies had finally crossed the Rhine into France.

Despite the breathing space he had been generously allowed, Napoleon still faced a formidable task: The Bohemian and Silesian Armies, commanded by Schwarzenberg and Blucher respectively, totalled some 250,000 men. Wellington with his Angle-Spanish army was on the Nive faced by Soult, whilst Suchet's troops were also tied down in the south.

Elsewhere Augereau's attempts to raise an army at Lyons were developing with frustratingly slow progress, Eugene's army in Italy, although quite formidable, was still tied down by superior numbers of Austrians and Murat chose this moment to treacherously change sides. Finally, 40,000 men of Bernadotte's Army of the North had entered the Netherlands; General Maison's corps of around 15,000 were in no position to offer effective opposition.

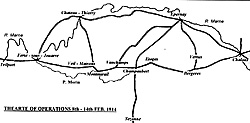

As January progressed the two Allied armies pushed back the meagre forces opposed to them. Eventually, on the 25th Jan, Napoleon could dally in Paris no longer; his presence, and all that meant to a demoralised army, was required at the front. His arrival at Chalons on the 26th immediately galvanised the army that was concentrating there and he quickly formulated his plans to throw back the complacent Allies. Aware that Blucher was moving towards Schwarzenberg in order to concentrate and induce him to march swiftly and directly on Paris, Napoleon planned to strike at the former's weaker army before this could be achieved.

Pyrrhic Victory

Unfortunately for Napoleon, although he was able to catch Blucher's army at Brienne on the 29th Jan the battle was indecisive. Despite occupying the field at the end of the day it was but a Pyrrhic victory and Blucher was merely pushed into the security of Schwarzenberg's outposts. It was of no consolation that the French had come within a whisker of capturing both Blucher and his able chief-of-staff Gniesenau. The fact that Blucher had escaped with just a bloody nose and Napoleon was unsure as to the Austrian's exact whereabouts restricted the French pursuit to taking up a position just south of Brienne, at La Rothiere, in order to fully concentrate.

Despite being able to gather most of his forces in this position Napoleon realised that he would soon face overwhelming strength and resolved to withdraw. On 1st February this movement had begun when the Allies attacked: Unable to disengage he was forced to hastily recall those formations that had already been despatched and fight a desperate battle, in snow and extreme cold, against an enemy twice his own strength. The result was almost a foregone conclusion despite the courage and tenacity of Napoleon's partly trained conscripts. With the loss of about 6,000 men, including 2,000 prisoners, and 50 or 60 guns the French were forced into a hasty night time withdrawal. Despite this significant reverse they were able to conduct a reasonably ordered retreat and by imposing a similar number of casualties on the Allies a rather tardy and ineffective pursuit was only launched after daybreak revealed the French had slipped away.

The news that Napoleon had suffered a defeat on French soil spread panic through Paris and despite a relatively unmolested withdrawal around 6,000 men deserted from the army: Napoleon needed a miracle to avoid total defeat. Luckily for him the Allies provided one for him. Instead of conducting a pursuit a l'outrance to destroy his army as Napoleon would have undoubtedly done, it was agreed that the two Allied armies would separate once more. Clearly it was believed that Napoleon was defeated and no longer a threat.

Blucher would take his Silesian Army and head for Paris along the valley of the Marne, whilst Schwarzenberg's Bohemian Army would follow the Seine to the same destination. Not only was Napoleon given the respite he required to rest and reorganise his demoralised army, but by standing as he did at Troyes he found himself in the perfect 'central position' With a rested army all he had to do now was to decide which army it would be most advantageous to attack first.

Prelude To The Battle

Despite Blucher having by far the weaker of the two Allied armies, Napoleon rightly considered him the most dangerous. Whether it was this that determined him to attack Blucher or the news that his corps had become dangerously spread out is unclear.

After his victory at La Rothiere and the agreement that he should conduct his own advance on Paris, Blucher set his army in motion with confidence: Napoleon himself had been defeated, his army dispersed and only Marshal Macdonald with a weak corps of about 9,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry stood between him and the French capital.

After his victory at La Rothiere and the agreement that he should conduct his own advance on Paris, Blucher set his army in motion with confidence: Napoleon himself had been defeated, his army dispersed and only Marshal Macdonald with a weak corps of about 9,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry stood between him and the French capital.

He set his own formations in motion: Yorck's Prussian corps was to pursue Macdonald down the Great Paris road which ran down the left bank of the River Marne from Chalons, through Chateau Thierry, La Ferte sous Jouarre and Meaux. Sacken's Russian corps would follow the "little" Paris road through Montmirail and on to La Ferte where he may anticipate Macdonald and crush him between the two forces. Olsufiew's weak Russian corps would follow Sacken a day's march behind and serve as a link with Blucher who was awaiting the arrival of Kleist and Kapzewitch with reinforcements. In all, Blucher had about 60,000 men.

Leaving a force of about 40,000 under Victor and Oudinot to face Schwarzenberg, Napoleon formed a mass de manoeuvre of most of his best troops to strike at Blucher. These included the two divisions of the Old Guard under Mortier, the two Young Guard divisions of Ney, Nansouty's three divisions of Guard Cavalry, Marmont's VI Corps and Defrance's Gardes d'Honneur; in all about 20,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry. If Macdonald's Corps could be co-ordinated with this force Napoleon might well expect to be able to conjure up a favourable result.

By the 8th February Macdonald had anticipated Blucher's attempt to cut him off at La Ferte sous Jouarre and taken appropriate steps to counter it. However, in their headlong charge forward the Allied corps stretched out over some 44 miles. Once Napoleon had confirmation of this he sent his forces in the direction of Sezanne. Marmont, who was already at this place, was sent north as the advance guard into the midst of Blucher's army. Although very slow progress was made at first due to the appalling condition of the roads the arrival of Napoleon immediately produced the necessary motivation. By the 9th February, Macdonald had successfully crossed the Marne at La Ferte and broken clean from the pursuing Yorck; it was now time to strike.

Russians Crushed

As he marched north from Sezanne on the 10th, Marmont ran straight into Olsufiew's corps of just under 4,000 men and 24 guns at Champaubert. In a short if bitter struggle, Olsufiew faced increasingly overwhelming odds as more and more French troops came up. With no cavalry to cover a withdrawal, the Russians were crushed: Only about some 1600 men and 15 guns escaped, Olsufiew himself was captured.

Napoleon now stood in the midst of Blucher's widely separated corps. He decided to turn west against Sacken's rear and wrote to Macdonald alerting him to the situation and ordering him to advance against Sacken in an effort to catch him between the two of them. Unfortunately, after his latest movement, Macdonald had arrived at Trilport and destroyed the bridge there, thus denying himself the means to follow the Emperor's orders and play a significant part in the next phase of the campaign.

At this stage Sacken was advancing on Macdonald at Trilport whilst Yorck was at Chateau Thierry. Blucher himself was at Vertus awaiting Kleist and Kapzewitch whom he had sent towards Sezanne to support Schwarzenberg. His plan was for Sacken and Yorck to concentrate at Montmirail with the aim of them fighting their way through whatever force had cut their communications, and he sent orders to them to this effect.

On the evening of the 10th Napoleon was at Champaubert. He sent Nansouty with two of his Guard cavalry divisions to seize Montmirail and reconnoitre beyond. Ricard's division of VI Corps was sent in support. The balance of the forces directly under his command were to follow on to Montmirail, except for the remainder of VI Corps and I Cav. Corps which, under command of Marmont was to watch for Blucher at Etoges.

Road State

The appalling state of the roads and the exhaustion of the troops made both Sacken's and Yorck's moves towards Montmirail painfully slow. Yorck seems to have realised that Napoleon would beat them there, took precautions to secure a withdrawal route back through Chateau-Thierry and sent messages to Sacken to join him at that town rather than at Montmirail. However, by the time this advice reached Sacken on the morning of the 11th, his advance posts were already in contact with the French east of Veils Maisons and he was preparing to attack what he considered to be only a weak force in front of him.

Nansouty had successfully carried out the mission entrusted to him by Napoleon: His Guard Cavalry had ridden into Montmirail, thrown out the Cossacks that were occupying it and then moved on to occupy the road junction where the routes from Veils Maison and Chateau-Thierry met. This was the junction where Sacken's and Yorck's routes would also meet. Having eaten his breakfast in Montmirail, Napoleon joined Nansouty on the high ground above the town. Here the Emperor was briefed on the situation: Sacken's cavalry were between Veils Maison and La Haute Epine and Yorck's cavalry had reached Viffort. Both were converging on Montmirail: The stage was set.

Climate And Terrain

The 10th February dawned clear and fine but this had finally broken a run of terrible weather. The battle at La Rothiere and the subsequent retreat had been conducted in snow and temperatures little above zero, and for the 5 days running up to Montmirail it had been raining steadily: The French march had been conducted using unpaved tracks, many soldiers had lost shoes in the mud and a combination of exhausting marches and miserable bivouacs ensured that even the hardiest of troops must have been in poor spirits and very tired. To make matters worse, much of the artillery was held up in the mud despite the best efforts of the locals who assisted with their own horses and labour. If there was any consolation for the French it was that the Allies were experiencing the same problems: These conditions were to do much to counter the Allied superiority in artillery.

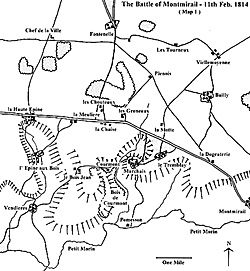

The battlefield of Montmirail (see Map 1) was bisected from east to west by the paved road that ran from Chalons to Trilport; the "Little Paris" road. This passed through Etoges, Champaubert, Montmirail, Veil Maisons and La Ferte sous Jouarre. Just to the west of Montmirail this was joined by the road running from Chateau-Thierry in the north along which the Prussians were advancing.

The battlefield of Montmirail (see Map 1) was bisected from east to west by the paved road that ran from Chalons to Trilport; the "Little Paris" road. This passed through Etoges, Champaubert, Montmirail, Veil Maisons and La Ferte sous Jouarre. Just to the west of Montmirail this was joined by the road running from Chateau-Thierry in the north along which the Prussians were advancing.

This was the junction occupied by Napoleon's forces. To the north of the Montmirail - Veil Maisons road the ground slopes gently to the north and is slightly rolling. This is not sufficient to provide much dead ground and is excellent cavalry country. Only a few small woods and farms provide any obstacles.

South of the road the ground drops more steeply down to the Petit Morin river which formed the southern edge of the battlefield. This area is also dissected by a number of ridges and gullies which make east/west movement very difficult. There are also a host of other obstacles such as farms and woods, the largest of which is the Bois de Courmont, which further makes an advance difficult despite a number of tracks. These obstacles, combined with the atrocious weather had made this part of the battlefield impassable to artillery.

The battlefield contained a number of villages which would feature in the fighting. The most important of these is Marchais. This village lay just in front of Napoleon's line and played a significant part in the battle. It sits on a promontory surrounded on three sides by slopes of varying degrees. Although containing only a small number of houses (even today), it's position makes it a natural fortress when approached from the west or south. The slope is particularly steep on the western side, the very side from which the Russians attacked. The approaches available to the French, the east and North, were far easier; indeed, from the east the ground is almost flat.

The Opposing Forces

There seems to be little agreement between sources as to the strengths of the two sides. Numbers for Sacken vary between 14,000 and 20,000, although it seems that after La Rothiere, and the hard marching since then, the lower end of that scale is perhaps most accurate.

Napoleon started the battle with about 11,000 men and was reinforced during the day up to a total of approximately 14,000; immediately available he had Nansouty's Guard Cavalry, Friant's 1st Old Guard Division and Ricard's 8th Infantry Division.

Ricard had 12 guns and there were 24 of the Guard. He could expect Michel's 2nd Old Guard Division, the Gardes d'Honneur and perhaps some more Guard Artillery to arrive during the day. Russian, Prussian and even some French sources claim that Ney's Corps of Young Guard were present throughout the battle.

However, in Anatomy of Glory, a respected history of the Guard, Lachouque is quite specific in stating that the Young Guard did not arrive in time to take part in the battle. Some confusion may stem from the fact that Ney himself was present, and actually led the decisive attack, so it is quite possible that some commentators have assumed that his troops were also. I have included the OB of this weak corps for those who tend to the Allied view. Yorck's Prussian Corps committed around 5,000 troops to the battle, having left one of it's three brigades at Chateau Thierry. This was tasked to secure the corps' line of retreat and protect the heavy artillery that was unable to negotiate the road to Montmirail.

Detailed OBs are shown elsewhere but it is important to understand the state that both the Allied and French armies had deteriorated to by this time. Corps and divisions were no longer the grand organisations of earlier in the wars: After the total destruction of it's armies in 1812 and 1813, and the hasty reorganisation just prior to 1814, the Grande Armée was a shadow of it's former self. For example, Ricard's 8th Division arrived at Montmirail only 1,800 strong and yet it was made up of the remains of 14 battalions. Only the Old Guard divisions were anywhere near up to full strength.

The situation in Sacken's corps was little better: The Russian Army tended not to send individual reinforcements to their regiments but simply raised new ones with which to replace those expended at the front. Therefore, as regiments sustained growing casualties they amalgamated their two battalions into a single one; this is reflected in their OBs for the Battle of Montmirail.

It is generally assumed that by this time in the campaign the Allied forces were grizzled old veterans and the French Marie Louises were immature and untrained conscripts. Although this may be generally true of the Allies the French forces should not be too hastily dismissed: Firstly, particularly at Montmirail, a high proportion of the troops involved in the major battles were Guard troops. By this time in the wars Napoleon was not prepared to go to the great lengths he used to save these excellent troops. Secondly, although the French Line formations were predominantly conscript, there was still a core of veterans and those conscripts who were still with the Eagles had fought at Brienne, La Rothiere and endured the demoralising retreat and appalling weather. Throughout the campaign, their tactical capabilities may have been decidedly limited but time and again they displayed outstanding courage and perseverance.

More Monmirail

-

Deployment, Plans, and the Battle

Large Photographs of the Battlefield (extremely slow: 338K)

Orders of Battle

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #36

Back to First Empire List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by First Empire.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com