The picture painted by my audience was therefore of a morally ordinary man who was a military genius, or at least a good general, but who certainly did not revolutionise the art of war, regardless of whether he was a good or bad thing for France, on which point there was no agreement at all. My own opinion was that Bonaparte as a man fell somewhere between 'ordinary' and 'bad'; he was definitely a bad thing for France; he was 'just a good general' rather than a genius - and he did not in fact revolutionise the art of war.

It was really this last bit that I was particularly interested in exploring, and I was gratified that everyone in my audience agreed that Bonaparte had not at all revolutionised the art of war (and I hadn't even prompted them to say that - honest!). However, to read some modern literature one could be forgiven for imagining that this was something of a minority view, since in recent times there seems to have been a massive upsurge in Napoleon-Worship.

Misplaced Bonaparte Hype

Personally I find this ethos and all the Bonapartist hype rather unsavoury and misplaced, since I believe that Bonaparte drew almost all of his inspiration from the Revolutionary Wars in which he was raised. If he had not run a military coup in 1799, some other general would surely have done so, just as his systematic use of aggressive wars had already been organised and practised by the Revolution from at least 1793 onwards. Bonaparte would have been a truly great man if he had been able to restore civilian government and bring an end to the round of aggression that the Revolution had initiated; but in the event he could do neither of those things.

If we look at just what aspects of warfare Bonaparte is supposed to have 'revolutionised', we find that most of them had already been invented before he came to command an army. Most of them had actually been invented during the Wars of Frederick the Great, and were distinctly 'Old Régime' in style, rather than Revolutionary. The parts that were not 'Old Régime' - such as the Levée en Masse, the abandonment of regular logistics and hence the resulting need for an Offensive d l' Outrance - were all products of the early Revolution rather than of Bonaparte. My list of the parts of warfare that Bonaparte is supposed to have 'revolutionised' would look something like this:-

Let us take these supposedly 'Napoleonic' innovations one at a time, in turn:-

Bonaparte certainly had his own particular methods of leadership and personal command but then so has every other general who has ever lived, and in the Revolution many of them inspired just as much loyalty among their own men, year by year, as he did. Indeed, one of the main worries of the revolutionary governments from 1792-5, starting with the highly popular Lafayette, was always that their generals were exercising only too much personal influence over their men.

Nevertheless the increasing importance of warfare to the Revolution meant that the power of generals did grow inexorably greater as time went on, and by about 1796 it was all but complete. Bonaparte was lucky to get his first army command at just this time, and so he was well placed to profit by the inevitable series of military coups that was bound to follow. But if it had not been him it would undoubtedly have been someone else indeed Augereau did actually run a coup, while Moreau remained the military equal of Bonaparte, as a commander, even as late as 1800.

Nor did Bonaparte even invent the system of one-man rule, since the Revolution had left the whole direction of the war in the hands of Carnot for several years, and in his way he exercised just as decisive a control over strategy as Bonaparte ever did. It is also important to remember that it was the Revolution, especially in 1793-4, that pioneered mass propaganda, and set up such things as army newspapers and political commissars, which had not previously been known. Equally the Revolution perfected the means of rooting out dissidents and political opponents, both within and outside the army.

Bonaparte had his own personal approach to these things, but basically he was just building on a structure that had already been set up. He was perhaps unique insofar as he personally came to control state propaganda and actually wrote some of the history books - and his legend was fostered by a strong political position within France for over half a century after Waterloo - but if one strips all that away and looks behind the hype, one finds just a typical French general of his age.

Many would object at this point, and protest that Bonaparte was not merely 'typical' in the way he ran his campaigns, but showed exceptional brilliance sufficient to qualify him for the title of 'genius'. Well, maybe a few of his campaigns did manage to display a certain brilliance - but we have to remember that that was not really exceptional in the warfare of the time. Several of his predecessors had also shown equal brilliance in some of their campaigns, for example within three short months in the autumn of 1792 Dumouriez had chased a Prussian army out of France, at Valmy, and an Austrian army out of Belgium, at Jemappes, all with French troops who were deficient in training, experience, officers, supplies and clothing. If that wasn't brilliant, it is hard to know what is.

Bonaparte is famous for his careful study of maps and statistics, and his organisation of staff officers to go out and animate each part of his army. However, the Revolution had - once again - already done all the key work for this, not least by the system of Representatives on Mission, or political commissars sent out from Paris to impose central direction on each of the eleven armies scattered around the frontier. These men are usually portrayed as nothing but blinkered ideologues who were a scourge on the army rather than a help to it - but in fact they were usually very intelligent and hardworking administrators who devoted themselves to improving the all-round efficiency of 'their' army (military, disciplinary and logistical as well as political) - and often they came onside with 'their' general against his rivals (e.g. Hoche on the Moselle vs. Pichegru on the Rhine).

The Representatives were also always in constant and rapid communication with the government in Paris, and participated enthusiastically in strategic debates, not only over the hiring and firing of generals, but also over questions of where the next offensive should take place, and how major formations could be transferred from quiet fronts to active ones.

The eleven armies of the Republic were not all spread evenly along the frontier, each minding its own business without central co-ordination, but were constantly subjected to a powerfully centralised and dynamic strategic direction. This was helped by the central position that France enjoyed in relation to her various enemies - and also to a very efficient postal system that allowed letters to move from Paris to the frontiers, and back, very fast.

Apart from the Representatives on Mission, each general also had his own Chief of Staff and staff organisation, consisting of men who had studied the full range of military science and the higher art of war. There had been specialist schools for all this since at least the Seven Years War, and it was by no means a new idea. By 1792 there was a recognised body of skills and knowledge that you had to possess if you were going to run an army or an army's staff, and during the Revolution there were at least a dozen - and probably many more - French generals who refused to take a major command just because they did not feel they had sufficiently mastered these sciences. Indeed, it was quite embarrassing to the Revolution that because most senior officers during the Monarchy had been noblemen, the necessary expertise was normally found among former nobles - the least politically correct class of all - and so it turned out that many of the most important jobs in the Revolution continued to be held by former nobles, for several years after such men had been rooted out of most of the less important positions.

This anomaly meant that the staff officers in question tended to be sacked, sooner or later, for political reasons - but it certainly did not mean that the Revolution had no staff officers or staff work.

Of Berthier

The case of Berthier is instructive. He would soon come to epitomise the very idea of Napoleonic staff work and efficiency - and judging by what happened when he was absent from Waterloo, we may even speculate that he was the real powerhouse of Bonaparte's military success. The thing to notice about him, however, is that he was already acting as Chief of Staff to three of France's absolutely most top-notch generals as early as 1792-3, i.e. Lafayette, Luckner and Biron; and he had already attracted Carnot's attention as a high-flyer. In other words the staff system at which Berthier excelled was already in place during the very earliest campaigns of the Revolution. It was scarcely Bonaparte's genius which invented it, or singled out Berthier for this particular role.

What did happen, however, was that precisely because Berthier was so successful under the early-war generals, he came under political suspicion very soon after they did, and suddenly found himself demoted and shunted off to the Army of Italy. He was already well in control in Italy when Bonaparte took command of that army, and so it would be quite wrong to suggest that Bonaparte himself had 'discovered' or 'created' him.

All the French Revolutionary commanders quickly discovered that warfare was disastrous and financially ruinous whenever they were fighting on the defensive or in retreat. That meant that they were not only losing territory and resources to the enemy, but they were also having to feed their armies from their own territory in the immediate locality of the armies themselves, thereby doubly weakening the state. Since all forms of logistic administration and financing had suffered a body-blow as a result of the political upheavals of the Revolution, the French found it a lot more difficult than the allies to set up well-organised magazines and depots along a regular line of communication stretching all the way back to the centre of their state.

The extreme example of this process was the Army of the Eastern Pyrenees, which received practically none of the supplies and reinforcements that were sent to it from central and northern France. These resources were hijacked at each stage along the way, in order to fuel all the other campaigns that were being fought simultaneously in Brittany, the Vendée, the Rhône valley and the Massif Central. The troops at Perpignan therefore had to raise all their supplies and recruits locally, imposing a very intense strain on a small area in order to fight what would otherwise have been a very 'limited' war indeed.

It was quickly realised that the way out of these problems was to carry the war to the enemy, 'living off the land', and thus feeding and paying your own army at his expense. This policy was also consistent with Revolutionary ideology, which wanted to export the new ideas of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity to all the oppressed peoples all over the world.

The Offensive

The Representatives on Mission were constantly pressing for the offensive, both in their role as political ideologues, and in their role as logisticians. They have left many relevant quotations from 1792-3 which stress the vital need to ATTACK - ATTACK - ATTACK at every possible opportunity. They knew that when the French DID attack, and captured places like Belgium, the Rhineland and Savoy, they almost always found themselves wallowing in piles of lovely loot which served to pay, feed and clothe the armies at the same time as they 'rewarded' the higher commanders themselves. In these circumstances the French found not only that they had to keep up the offensive pressure, but they also at all costs had to avoid the risk that peace might break out (apart from a peace of total domination, that is, as e.g. over Savoy or - less complete but just as effective - over Spain). Not only did the wars have to be waged offensively, but they also had to be waged continuously.

The faster marching that sprang from living off the land may not have represented a very major additional advantage to the French in many of their 1790s campaigns - but it did represent an advantage of sorts, and it was yet another element that Bonaparte would always try to exploit in his own operations. Nevertheless it WAS always a very vicious and unsafe system that could be used effectively in only very specific and local circumstances. The more it was extended into a generalised system, the more it was liable to come unstuck.

Bonaparte himself would discover this in Egypt, East Prussia, Russia, Spain - and even in some of his more successful thrusts up the Danube - but his problem was that he really never had any alternative to offer. Because he found himself committed to a system of remorselessly aggressive offensive wars, in order to balance the national budget, he found himself equally committed to a reckless system of fast marching, and living off the land. This meant that he was left with very few options at any of the diplomatic, strategic, operational or tactical levels of action. In all this he was very similar to his immediate predecessors in the Revolutionary Wars.

Decisive Short Wars?

Bonaparte is also credited with having invented the idea of Decisive Short Wars that captured the enemy's capital city, especially by contrast with such hesitant and indecisive campaigns as those of the Austrians and Prussians in 1793. However, the Austrians and Prussians were limited in their aims as much by political as by military constraints, and in fact there was a very heated debate within their high commands, about whether or not it was militarily better to go for the enemy's jugular rather than for his peripheral fortresses. The so-called 'unfortunate General Mack', for example, was always trying to get his superiors to march on Paris from Belgium. He must therefore presumably be counted as more 'modern' than Bonaparte, because he was already calling for a 'Napoleonic' type of campaign some three years before Bonaparte would occupy even Turin - and fully twelve years before he would occupy Vienna.

Secondly, it is not a matter of mere theory or aspiration, but of hard historical fact, to notice that Dumouriez occupied Brussels in 1792 and Pichegru occupied Amsterdam in 1794. In neither case was there any love of fruitless skirmishing among the border fortresses - but a solid determination to press home deep into enemy territory, and capture his capital cities. Still more to the point, perhaps, is the New Morality which the Revolution had brought to these matters, since its new definition of human rights made it a patriotic duty to overthrow all monarchical governments wherever they might be found.

Well over a dozen principalities or ecclesiastical states had therefore been overrun in their entirety, and without any of the traditional appeals to legitimacy or law, before the Revolutionary Wars were even a year old. Once again, in fact, the deep-striking and annihilating Napoleonic campaigns in Italy and later on the Danube turn out to have been merely aping and copying a pattern that had already been well established in earlier days.

When we look at the wars of the early Revolution, however, we find repeated attempts to manoeuvre against the enemy's rear, by both sides. The Duke of Brunswick had tried it in the Valmy campaign of 1792, for example, and General Mack had tried it at Caesar's Camp (Near Cambrai) in early '93 - just as Dumouriez had earlier tried it at the battle of Neerwinden and Hoche tried it in the relief of Landau, late '93. There was nothing new about it, since Frederick the Great had often tried to achieve something similar. It was, after all, the logical extension of his famous 'oblique attack'.

Now, not all of these manoeuvres were successful in fact most of them failed (just as quite a lot of Bonaparte's would fail) - but that is not the same as saying that they were not attempted, or not held up as an ideal. A manoeuvre against the enemy's rear was very much the 'in' thing to do at this time, just as it was fashionable to attack at night in order to achieve surprise, or to attack across unpromising terrain that the enemy might not be defending in full strength.

The classic case of the latter was Pichegru's capture of the Dutch fleet by attacking it over a frozen stretch of sea - using cavalry - but there were all sorts of other examples from the early Revolution of unlikely assaults:- up steep mountains in the Pyrenees or the Rhineland; across the Rhine river (without the benefit of a bridge); or over the canals of Flanders. The idea of 'attacking the enemy where he ain't' was therefore very much a standard approach in the 1790s, and did not need Bonaparte to invent it.

French Art of War in the 1790s (Part 2)

Letter to Editor Response: FE#35

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. This article is based on the talk I gave at the 'First Empire' Day held in Bridgnorth on 29th Thermidor, Year CCIV, at the invitation of citizen Watkins. My main subject was 'The French Art of War in the 1790s', which is the subject of a book that I am currently writing. However, I started off by asking the audience some questions about Napoleon Bonaparte, whom I tried (but often failed) to refer to as 'Bonaparte' rather than as 'Napoleon' (In this I was following the example set by Correlli Barnett in his excellent 1978 book, entitled Bonaparte, about the great Emperor's many failings). Anyway, the results of my questionnaire (which had 22 participants) were as follows:

This article is based on the talk I gave at the 'First Empire' Day held in Bridgnorth on 29th Thermidor, Year CCIV, at the invitation of citizen Watkins. My main subject was 'The French Art of War in the 1790s', which is the subject of a book that I am currently writing. However, I started off by asking the audience some questions about Napoleon Bonaparte, whom I tried (but often failed) to refer to as 'Bonaparte' rather than as 'Napoleon' (In this I was following the example set by Correlli Barnett in his excellent 1978 book, entitled Bonaparte, about the great Emperor's many failings). Anyway, the results of my questionnaire (which had 22 participants) were as follows:

Question Replies Was Bonaparte a good man? Good man: 0 Neither: 17 Bad man: 4 Was Bonaparte a good thing for France? Good: 7 Neither: 5 Bad: 9 Was he a military genius? Genius: 10 Just a Good General: 12 Bad Geneal: 0 Did Bonaparte revolutionize the art of war? Yes: 0 Made a Few Improvements: 18 No: 4 1) The Cult of Personality / La Gloire:

2) Strategic Preplanning and Meticulous Staff work:

3) Belief in the Offensive à Outrance:-

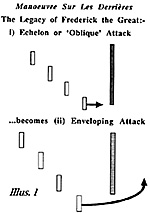

4) Manoeuvre Sur Les Derrières:- (see illustration 1)

Whatever else he is supposed to have been good at, Bonaparte is supposed to have invented the Manoeuvre Sur Les Derrières or attack on the enemy rear. Commentators like Jomini would make a great deal of this, and would create a whole science of strategic and operational geometry based on the angle between an army's Line of Communication and its Line of Operations.

Whatever else he is supposed to have been good at, Bonaparte is supposed to have invented the Manoeuvre Sur Les Derrières or attack on the enemy rear. Commentators like Jomini would make a great deal of this, and would create a whole science of strategic and operational geometry based on the angle between an army's Line of Communication and its Line of Operations.

Letter to Editor Response: FE#37

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #34

© Copyright 1997 by First Empire.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com