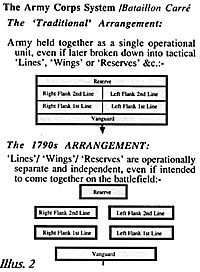

5) The Army Corps System / Bataillon Carré (See illustration 2)

There has been a lot of discussion and a lot of disagreement over the precise moment when first the Division and secondly the Army Corps was first invented. My own opinion is that the Division dates back to at least the 1760s, and the Army Corps to at least the earliest years of the Revolutionary Wars. By about 1793 the armies already tended to be organised into distinct groupings of brigades and Divisions that were actually equivalent to Army Corps, even if they might have different names such as 'The Right Wing', 'the Left Wing', or 'The Reserve'. Of particular interest in this is the practice, apparently standard in all armies, of having a specially-designated 'Vanguard', consisting mainly of light troops of all arms, which had the duty of reconnoitring and fixing the enemy while the main body came forward to fight the main battle.

There has been a lot of discussion and a lot of disagreement over the precise moment when first the Division and secondly the Army Corps was first invented. My own opinion is that the Division dates back to at least the 1760s, and the Army Corps to at least the earliest years of the Revolutionary Wars. By about 1793 the armies already tended to be organised into distinct groupings of brigades and Divisions that were actually equivalent to Army Corps, even if they might have different names such as 'The Right Wing', 'the Left Wing', or 'The Reserve'. Of particular interest in this is the practice, apparently standard in all armies, of having a specially-designated 'Vanguard', consisting mainly of light troops of all arms, which had the duty of reconnoitring and fixing the enemy while the main body came forward to fight the main battle.

In the years around 1900, when the French Army was trying to work out how best to fight the Germans in future, this 'Vanguard' function would come to occupy a major place in the debate, and from there it would become enshrined in Joffre's 'Plan XVII', by which the first three weeks of the Great War would be fought. But around 1900 the whole vanguard' idea was being quite erroneously attributed to Bonaparte, when in fact it ought to have been credited to all the earlier armies of Europe who had fought in the wars of Frederick.

One difficulty with the view that the early Revolution that invented the Army Corps is that the precise composition of the 'Army Corps' at that time tended to change from moment to moment, in a way that would no longer be true, to the same extent, under the First Empire. Yes, it's true that the Army Corps was systematised rather more under Bonaparte than under Carnot - but even under the Great Emperor it did not always retain a constant composition, and by the time of the greatest war of all - in 1914-18, it was quite liable to change almost week by week.

The key thing was surely the idea that there should be a particular 'Corps Commander', with his own familiar staff, who would be responsible for a major portion of the army as an independent command. That idea was already well entrenched in the early 1790s, and so all that Bonaparte did thereafter was tinkering with the details.

Admittedly the concept of multiple independent commands within an army could also be very dangerous. If each individual sub-unit was allowed to go its own way - regardless of whether it was called a 'Division', a 'Corps' or some other designation - there was clearly a risk that it would fail to co-ordinate its action with the other sub-units of the army, or that it would be cut off by the enemy and destroyed in detail. Many of General Mack's plans, for example, have been criticised very deeply for their excessive complexity and multiplication of isolated 'columns'. He normally liked to have as many as eight separate columns advancing on the enemy to encircle and annihilate him - but in practice they often failed to start at the same times or keep to their intended directions. Each one was often exposed and vulnerable to local defeats by locally superior numbers - a mistake that the Austrians would again commit, still more spectacularly, in their repeated attempts to relieve Mantua in 1796.

Nevertheless, although Bonaparte was able to exploit this mistake on that last occasion, he did also sometimes occasionally make exactly the same mistake himself. At Ulm in 1805, when he finally defeated and discredited Mack himself, he was actually in danger of being caught out in detail, because his various Army Corps were so widely spread. Then again one might cite the detail defeat of Vandamme at Kulm in 1813, or of almost all of 'the Peninsular marshals', at one time or another, in Spain.

It has often been said that the Army Corps system allowed Bonaparte to advance into enemy territory with his forces spread out on a wide front (in the 'Bataillon Carré'), but then to bring together all the parts together at a single time and place, to fight a Decisive Battle with Superior Numbers. I would certainly agree that the use of Army Corps did give this type of flexibility - but I would still say that something very like it was already being used during the first four yea's of the Revolutionary Wars. There were certainly plenty of decisive battles with superior numbers - and those numbers could have been concentrated on the battlefield only if each part of the army had been properly organised, articulated and co-ordinated by high-quality staff work.

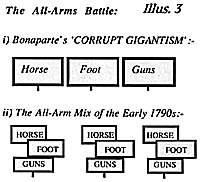

6) The All Arms Battle: (See illustration 3)

Bonaparte has also been credited with having somehow invented the 'all-arms battle', or 'the intelligent combination of the three arms'. He is remembered for his massed Cuirassiers, his massed grand batteries of Artillery and his massed columns of Infantry. This folk-memory is fail- enough as far as it goes, insofar as he really did try to employ each arm in great masses - but we surely have to reflect that this in itself was not necessarily the same thing as 'combining the three arms intelligently'.

Bonaparte has also been credited with having somehow invented the 'all-arms battle', or 'the intelligent combination of the three arms'. He is remembered for his massed Cuirassiers, his massed grand batteries of Artillery and his massed columns of Infantry. This folk-memory is fail- enough as far as it goes, insofar as he really did try to employ each arm in great masses - but we surely have to reflect that this in itself was not necessarily the same thing as 'combining the three arms intelligently'.

Surely the bigger the mass of each arm that you use, the less chance you have for effective co-ordination with other arms at a low (or 'minor tactical') level. There were a number of very varied reasons why Bonaparte was condemned by his subordinates, immediately after Waterloo, for his so-called 'corrupt gigantism' - but this specifically tactical consideration was certainly one of them. Indeed, the battle of Waterloo was itself a classic example of the problem. It started with a massed artillery bombardment: then there was a massed infantry attack: and after that there was a massed cavalry charge. It therefore exhibited the USE of all three arms - but very sadly there was N0 actual 'Co-ordination' between them, whatsoever.

In the battles of the early Revolution, by contrast, both sides seem to have been far more ready to mix up small units, of all arms, in a single tactical grouping. There were inequalities between the two sides in this process - for example the French enjoyed a certain superiority in artillery, especially in horse artillery (which they had invented in 1792 and which immediately became respected by both sides) - but the Allies had by far the better cavalry, leading to a series of frantic (and doomed) appeals to patriotic Jacobin clubs to furnish horses, riders, tack, and every other type of horsey equipment. The French infantry was never up to the standard of the Allied infantry, although it was often considerably more numerous.

Nevertheless the fact remains that in the wars of the Revolution all three arms were mixed together at low tactical levels, by both sides and on repeated occasions, far more regularly than would be the case in the First Empire.

What we see in all this is that Bonaparte did not really innovate in anything very much - but merely used what he found already there. If he happened to do particularly well, it may well have been because of his personal genius - but it was also surely because he came in late in the Revolutionary Wars, and so was able to exploit the lessons already learned in them, and all the experience gained. We have also seen that these lessons and this experience was often merely reaffirming the whole accepted method of doing things that was already being used by all the main European armies - much of which had been developed during the wars of Frederick the Great.

French Art of War in the 1790s (Part 1)

Letter to Editor Response: FE#35

Letter to Editor Response: FE#37

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #34

© Copyright 1997 by First Empire.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com