Just the Facts

Let's determine the facts. Since it is evident that in most cases an eight company battalion is illustrated in the Règlement 1791, as pointed out by Jean Lochet himself, it is clear that the grenadier company is usually absent. So, it is patently obvious that the detachment of grenadiers was sanctioned. Any other conclusion can only be construed as a wilful refusal to recognize the evidence.

As far as skirmishers are concerned the Règlement 1791 suggests that "some men" be taken "from the third ranks". So it appears that skirmishers are sanctioned too.

Anyway, this is the passage "in the Règlement that addresses the grenadier company's role" mentioned by Jean Lochet.

"The grenadier platoon follows the movement of the half battalion of which it is part, and conforms to that which was prescribed above; with the single difference that it shall place itself behind the interior sections of that last subdivision of the column in such a manner as to be flanked on the left and right by the two exterior sections of this subdivision" sections of that last subdivision of the column in such a manner as to be flanked on the left and right by the two exterior sections of this subdivision"

There can be no argument about this, certainly not from me. However, I am bound to point out that since I did not say that grenadier peletons never functionioned with their parent battalions, Jean Lochet's point eludes me.

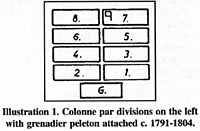

Never mind, the passage does describe a nine company column that is neither one thing nor the other. My illustration of the arrangement, adapted from Schwarz by the addition of the grenadier company, is at Illustration 1. The only comment I would make is that the resulting column is no longer a colonne par divisions in either the spirit or letter of the 1791 Règlement.

Never mind, the passage does describe a nine company column that is neither one thing nor the other. My illustration of the arrangement, adapted from Schwarz by the addition of the grenadier company, is at Illustration 1. The only comment I would make is that the resulting column is no longer a colonne par divisions in either the spirit or letter of the 1791 Règlement.

No Help

Be that as it may, it is still no help in determining what happened after the establishment of a voltigeur company in 1804; quite what the detachment of the voltigeur company from such an arrangement would result in hardly bears further consideration. Something of a 'dog's breakfast' it would seem and, I suggest, not one to be utilized under tactical circumstances.

However, let me return to "The portion of the Règlement of 1791 pertinent to the school of the battalion" alluded to by Jean Lochet, in an attempt to reconcile his apparently incompatible statements in the context of grenadier companies. This is the Ecole de Bataillon/Die Bataillons-Schule and I have it open in front of me as I write.

Large version of illustration 2 (34K)

Large version of illustration 2 (34K)

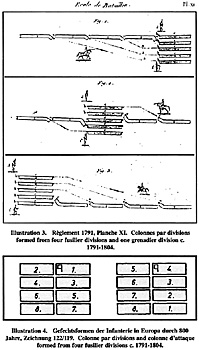

A brief perusal of the associated plates starting with Planche IX shows that the battalion illustrated consists of ten companies organised in five divisions, a theme that continues through to Planche XXII when it changes to an eight peleton, four division battalion, epitomised

by the notorious colonne d'attaque which is shown at Illustration

2.[19] Fig 1 shows 'ployment' from line into column, Fig 2 shows deployment 'en tiroir'. John Lochet's statement, therefore, that "all battalion maneuvres" are illustrated " with an eight-company battalion which excludes the grenadier company", is incorrect.

The reason for the presence of ten peletons is quite straightforward. The two grenadier peletons of the regiment are being illustrated and described, functioning tactically as

a division, as part of a five division battalion. Any claim that "the grenadiers did not form a division with the fusiliers" is, therefore, also incorrect. The text describing a five division battalion, including a grenadier division, 'ploying' by divisions into column behind the right (grenadier division) says,

"One sees that the first division arrives, wheeling by files to the rear at a distance of three paces parallel to the one of the grenadiers".[20]

This is clearly shown at Fig 1 to Illustration 3. The grenadier division stands on the right of the line whilst the four fusilier divisions 'ploy' into column behind it. Figs 2 and 3 show the same conversion conducted on centre and left divisions respectively.

It is true to say, however, that the 1791 Règlement illustrates a four division battalion throughout the remaining part dealing with the multi-battalion environment, Evolutions de Ligne, and this formation does dominate generally, which is further evidence that the detachment of grenadier companies was not only sanctioned, but usually expected.

Voltigeur Conversion

In 1804 the second fusilier company, some sources say the third, was converted to a voltigeur company, but this is an irrelevance as far the 1791 Règlement is concerned since it does not recognise such a sub-unit. The battalion sub-unit structure was unchanged at nine companies, 1 grenadier company, 1 voltigeur company and 7 fusilier companies, all with

different establishments. However, the 1791 Règlement only illustrates colonnes par division with even sub-units, eight or ten companies. This 'square' divisional arrangement is described and illustrated, exclusively, throughout the 1791 Règlement.

Schwarz's rendition is at Illustration 4.[21]

At the risk of being repetitive, the construction one can reasonably place on all this, in my view, is that when detachment of a company produced a battalion of uneven companies, it would no longer be able to form colonne par divisions or, in other words, that a divisional column should be 'square' and, therefore, that when an uneven number of companies were present colonne par peletons might be adopted if at all possible, or that entire battalions might be deployed to skirmishing to avoid "deranging in any way the ensemble of the corps". Based on the consistent evidence in the 1791 Règlement, together collateral from

elsewhere, this seems not unreasonable.

So, as far as the 1791 Règlement and the nine company battalion is concerned generally, I think it is fair to summarise as follows.

The development of the nine company battalion up to 1808 appears to have resulted in an inflexible tactical tool. The detachment of grenadier companies to form independent

battalions was becoming unfashionable and the resulting nine company service battalion was no longer 'square' and, therefore, tactically clumsy. This is evidently George Nafziger's view. "When issued, the Decree of 18 February (1808) resulted in a massive reorganisation

of the French infantry and reduced most battalions from a nine company organisation to a six company organisation. The use of converged grenadier battalions was disappearing and, for tactical reasons, the battalion needed to have an even number of companies".[22]

Although the six company battalion has already been mentioned in passing, the thrust of much of the discussion so far has been concerned with the pre-1808 nine company organization.

The difficulty now encountered is this. By 1804, because of the introduction of the voltigeur company, the 1791 Règlement was obsolescent, which became even more marked when the battalion organization was reduced to six companies in 1808 and, therefore, to apply the 1791 Règlement to the post 1804 situation requires the application a degree of extrapolation.

The part of the Decree of 18 February 1808 relevant to this particular discussion, and alluded to by John Koontz in EEL86 says this.

"6. In battle the grenadier company will be on the right of the battalion and that of the light infantry on the left."

"7. When the six companies are present with the battalion it will always march and act by divisions. When the grenadiers and light infantry are absent from the battalion

it will always manoeuvre and march by platoon. Two companies will form a division; each company will form a platoon; each half company a section."[23]

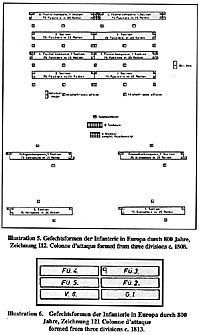

The detailed diagram of the arrangement for a colonne d'attaque from Schwarz is at Illustration 5 [24]. Riehn, in his discussion of Napoleonic tactics also describes this column.[25] The more familiar alternative, also from Schwarz, is at Illustration 6.[26] Riehn attributes the later, wider, formation to approximately 1813

"It has generally been assumed that this arrangement came into use only during the post war era, but the general order issued by Napoleon on the eve of Leipzig contradicts this."[27]

This, I think, may be subject to dispute but it is not relevant to the matter under discussion.

From Belhomme

Jean Lochet provides a passage from Belhomme, which is apparently taken from the Manuel d'infanterie ou Resumé de tous les Règlements, Décrets, usages, et Renseig-nements propres aux Sous-Officiers de cette Armée, 1813 as follows.[28]

Dans les manoeuvres les compagnies formaient un peleton de deux sections. Lorsque les seize compagnies étaient présent, elles se rangeaient de la droit à gauche

dans lordre suivant: grenadiers, 3e, 1er, 4e, 2e, voltigeurs et le bataillon manoeuvrait toujours par division. Lorsque les compagnies d'élite étaient détachées les compagnies se rangeaient dans l'ordre suivant: 1er, 3e, 4e, 2e et le bataillon manoeuvrait par peletons."

This translates to the effect thus,

"Tactically the companies formed a platoon of two sections. When the six companies were present, they were drawn up from the right to left in the following order: grenadiers, 3rd, 1st, 4th, 2nd, voltigeurs and the battalion always manoeuvred by division. When the elite companies were detached the companies were drawn up in the following order: 1st, 3rd, 4th, 2nd and the battalion manoeuvred by platoons".

It is essentially a reflection of the Decree of 18 February 1808. Unfortunately we are no further forward but based on this evidence Jean Lochet states.

"Thus, I believe we can dismiss Mr Cook's claim's in First Empire 16 and 17".

Unfortunately, this refers largely to the hierarchy of a battalion in line so I simply do not know what the claims he alludes to are. Moreover, my article in FE16 does not discuss the French at all!

Be that as it may, the opening sentence of Article 7 of the Decree of 18 February 1808 is seemingly unambiguous.

"When the six companies are present with the battalion it will always march and act by divisions." Does this also mean that the battalion did not manoeuvre by divisions when the six companies were not present? Unfortunately the issue is confused by the subsequent reference to the absence of the two elite companies. "When the grenadiers and light infantry are absent from the battalion it will always manoeuvre and march by platoon." Does this mean the battalion only manoeuvred by companies when both flank companies were absent and the battalion was reduced to four centre companies, or does it mean when one or the other

flank company was absent.

Same Question

We are, therefore, left with the same question. What happened when the voltigeur company was detached and only five companies were present? Should we infer from all this that when the voltigeur company was absent that the battalion manoeuvred by companies? The colonne par peletons is an available option which receives significant coverage in the 1791 Règlement, albeit in the context of the earlier larger battalion. It would

certainly be appropriate under the circum-stances where a battalion was reduced to uneven companies, it was an option documented in the 1791 Règlement and one supposes it was there for a good reason, presumably for use under certain tactical circumstances,

of which this seems an obvious one. I see no reason to exclude the possibility that it probably saw more use than is popularly thought.

Jean Lochet's view in EEL 14 is that Belhomme, and Jean Lochet,

"Clearly state that only when both elite companies were away, i.e. reduced to four fusilier companies, the battalion operated by platoons."

This can certainly be argued and although I do not dismiss it, nowhere in any version, except Jean Lochet's translation, have seen the word 'only' appear. Faced with ambiguity such as this and the absence of any clear information in the context of what happened when an uneven number of peletons was produced, conclusions such as Jean Lochet's seem somewhat peremptory.

One further passage from EEL itself is of interest.

"Many sources describe all French columns as columns of attack, or offer diagrams of columns on the middle only. In fact this was very far from being true. This column seems not to have received much use at all in the Imperial period. There are two reasons for this statement. First in most cases, a battalion would have been operating with one or more of its flank platoons detached as skirmishers. In this case, as has already been mentioned, the column in use would have been a column of platoons."[29]

I agree with this conclusion. It would apply even more to a colonne par divisions where the grenadier and voltigeur companies are positioned at front and rear respectively, or vice versa depending upon whether the column is formed on the left or right flank, rather than both at the rear as in the colonne d'attaque.

Be that as it may, the likelihood that a battalion formed in any variety of column of divisions could detach one or both of its flank companies in a tactical setting, and indulge in kind of 'musical chairs' necessary to reverse the disposition of the 1st and 3rd companies to reorganize itself into the four company hierarchy described, is, in my view, simply wishful thinking. It is almost inconceivable that such a conversion would have been conducted on the battlefield and it seems likely that it was intended when both flank companies were detached to

elite battalions on a long term basis, which still occurred when the 1808 decree was promulgated, rather than in an ad hoc fashion in response to an immediate tactical problem.

The benefits of having a battalion in a symmetrical formation, be it by divisions or companies, are that it facilitates the normal process of breaking the line into column, column into line and into and out of square. In my opinion, attempting these with an asymmetrical formation, with the unavoidable differences in frontages and associated deploying distances, would be rendered much more difficult to accomplish and was probably avoided if at all possible.

Although I am certain that nothing was done which was not contained within them, and whilst one cannot underestimate the importance of the regulations and other associated official documents, relying exclusively on these texts, particularly the 1791 Règlement, is rather like loosing something in a room but only looking for it in the corners. These documents

do not always fully explain the cardinal enigma of what soldiers actually did on the battlefield.

It is necessary to examine the regulations in conjunction with the countless glimpses, provided to us by numerous eye-witnesses, of what actually happened in certain circumstances.

Unfortunately, the problem with these is manifold. First and foremost they are no more than glimpses, representing a minuscule exposure in comparison with the whole, which must be largely unreported. Moreover, these may be written by witnesses who are not be reliable, or whose motive for recording what they saw is not known and may be reporting something simply because it is not typical. These are factors we are frequently unable to determine and so, taking the mass of evidence, a degree of extrapolation and judgement is a necessary part of the investigative process. It is also worth remembering what Richard Riehn had to say in the context of a

lack of empirical experience,

"This, in turn, gave rise to some amateurish notions that were rooted in a general lack of knowledge of practical details, which also gave Schwarz (see footnote 9) cause to complain in his massive work on eight centuries of infantry tactics"[30]

Although I would not be so impolite as to dismiss Jean Lochet's rather narrow point of view in the discourteous way he regularly reserves for those with whom he does not agree, I do not have the confidence in Jean Lochet's infallibility that he appears to have himself.

Letter to Editor Response: FE#35 This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Large version of illustration 3 and 4 (slow download: 124K)

Large version of illustration 3 and 4 (slow download: 124K)

Large version of illustration 5 and 6 (slow download: 118K)

Large version of illustration 5 and 6 (slow download: 118K)

or Jumbo version of illustration 5 and 6 (very slow download: 329K)

Footnotes:

[19] Règlement of 1791. Ecole de

Bataillon. Pl XXVI

[20] Ibid. Pl XI and p29 Fig 1re.

[21] Schwarz. Vol II, Zeichnung 121.

[22] FE 9. GF Nafziger. The Decree of

18 February 1808. p4.

[23] Rogers, HCB. Col. Napoleon's Army,

London, 1974. p62. This is a translation from the French found

in Saski. C, Cdt. Campagne de 1809. 3 Vols, Paris, 1899-1902.

I do not have access to an original French version and I take

the translation on face value.

[24] Schwarz. Vol II, Zeichnung 112.

[25] Riehn. p129.

[26] Schwarz. Vol II, Zeichnung 121

[27] Riehn. p134.

[28] The Manuel d'infanterie 1813 (The

Infantry Handbook, or summary of all the regulations, decrees,

practices, and particulars appropriate to non-comissioned officers

of the Army) is a summary of all changes since the publication

of the 1791 Règlement.

[29] John E. Koontz. EEL Vol 1 86, p24.

[30] Riehn. p94.

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #33

© Copyright 1997 by First Empire.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com