In issue 27 I wrote about Prince Eugene de Beauharnais' baptism of fire at the Battle of Sacile, but what happened after. How did the Viceroy of Italy manage to turn things around and arrive on the field of Wagram as a confident and experienced general?

After Sacile, the Austrians should have finished off Eugene, but it is little surprise that the Archduke John was not capable of such a feat, and before long the numerical advantage and the initiative had returned to Eugene. Napoleon had really chewed out Eugene in a series of letters which amount to severe censure, and which hurt Eugene deeply. He rallied quickly.

The army retired behind the line of the Piave River, although Eugene intended to retreat further on the Adige-Alpone line. Napoleon had at first suggested to his stepson that the Piave was suitable to defend, but Eugene' local knowledge told him that the river was easily fordable for much of its length, making outflanking a serious possibility.

Having decided on a further retreat, Eugene began ditching some of the read wood that contributed to his defeat. Barbou was posted to the Venice garrison. Satisfied, Eugene pulled back, with the ever-cautious John happy to let him go. By April 28th Eugene was in position and for the first time his army was concentrated. His troops now included a dragoon division under Grouchy and another of infantry commanded by Durutte. Including the garrison of Venice he had close to 55000 men. Furthermore they were behind strong defences. Things were beginning to look up.

Meanwhile the Austrians were suffering supply chain problems, having to continually detach troops in a manner similar to that which Napoleon would experience in 1812. By the time he arrived at the Adige-Alpone line, John did not have the manpower to force it.

Meanwhile Eugene's Army of Italy was undergoing a re-organisation into proper corps. This had been delayed until Napoleon had appointed the commanders. They were to be Marshal-to-be Macdonald, Baraguey d'Hilliers and Grenier. Macdonald turned up in late April, and with his arrival began the series of spurious lies and half truths which contributed to him getting a baton rather than the deserving Eugene. Despite his late arrival Macdonald claimed that it was his idea that the army retreat to its current position, and that he personally cheered up a virtually suicidal Eugene. All this is palpable guff and betrays Macdonald for the fabricator that he was. Of the others, Grenier was sound, but Baraguey was a bit of a bottler.

Relieved of Command

Napoleon the whole time was beginning to lose faith in Eugene, compounded it must be said by Eugene's very sketchy report about Sacile which unknown to him had in fact cast him in a worse light because Napoleon believed that he was incapable of beating the Austrians in a straight scrap. On April 30th the Emperor decided to relieve his stepson, and a dispatch was sent. Its contents effectively appointed Murat, erstwhile King of Naples, to the command.

This letter did not arrive, however, until May 6th, by which time circumstances had somewhat changed. By the end of April the Viceroy was ready to regain his credibility.

At the beginning of May, the armies were facing each other across the Adige-Alpone line, with the main formations facing on a two mile front between Arcola and the Alps. Eugene was at Caldiero and John at Villanuova. The archduke had counted on support from Chasteler in the Tyrol, but Marshal Lefebvre's operations in that area had put the mockers on that. The Army of Italy's last piece had meanwhile arrived: General Count Sorbier, an artillery commander. At last Eugene was able to form a capable artillery reserve. The elan in the army had also improved, ironically, because of the officer casualties at Sacile. With promotion based on ability, a fresh new crop of officers were eager for success and glory, and Eugene made sure they were fed with both.

The Viceroy formed an elite advance guard brigade, made up of detached voltigeur companies and a squadron of Chasseurs. Sahuc had commanded the first version, but had proved a total waste of time at Sacile, so Eugene wisely picked a young brigadier half Sahuc's age - Armand-Louis Debruc. All that Eugene had to decide was where to attack. After some deliberation he decided on a right hook, pinning John at Villanuova. A number of successful skirmishes helped boost morale, as did the impending arrival of Fontanelli, whose division would bring the combat strength of the Army of Italy close to 45,000. Just as he planned to attack, John did what he did best. Retreated.

News of Napoleon's campaign was reaching Italy, and the timid Archduke did not like what he as hearing. In truth, John had convinced himself that the cautious tactics which brought victory at Sacile - he did not realise that Eugene had lost the battle rather than he had won it - were suitable for war in general. News of the scores from Bavaria unsettled him, as did the increasing size of his enemy. John began to have a few doubts of his own. Realising that he could not hold Eugene if he suddenly attacked, John began withdrawing on the Piave River line. He had approximately 40,000 troops on hand.

Austrian Retreat

On May 2nd he was off.

The bridges on the Alpone were broken down, and the day's delay in repairing them gave the Archduke some breathing space. His opponent, realising that all earlier plans had been made irrelevant, no detached Durutte's division to operate against John's left. The main body were led off by Debruc, who got himself wounded bravely attacking Frimont at Montebello. He was replaced by Colonel Renaud from the 30eme Dragoons. On May 3rd Eugene came up on the Austrians who were holding Citadella on the Brenta River. However, Eugene was not fool enough to attempt a rash assault. Not any more. He guessed that John was heading back for the Piave, and he bided his time. He ordered a general concentration on the Piave, near Treviso.

John held on at the Brenta only long enough to facilitate the withdrawal of the Venice blockading troops. Late on May 6th he was over the Piave. By the following morning Eugene was facing him once more. At that moment the Viceroy received Napoleon's letter relieving him of command.

Rather impressively, at least to my way of thinking, Eugene decided to ignore the letter. It instructed him to write to Murat and invite him to take command, but the Viceroy knew that he was on the verge of success. He also knew that Napoleon would forgive him in an instant if he brought victory with him. After all, he knew his own stepfather rather well. He also knew Murat, and didn't trust that buffoon with anything that didn't have four legs.

Eugene had decided to go all out across the river and crush John. To pin him he decided to expand the advance guard to divisional strength and give it to a dashing young brigadier - Dessaix, who came highly recommended from Broussier's division. It was a wise choice. Eugene knew that facing his 45,000 troops John could now only muster about 30,000 men. The tricky bit was crossing the Piave.

The Archduke was centred on Conegliano

some 8 miles from the furthest of the three fords on

the eastern bank of the Piave. The terrain between

was flat, crossed by dikes and streams, and the 8eme

Chasseurs who had been sent to scout ahead reported

that if the crossing was made in the early morning

when the river was low it could be accomplished.

The river all along this section is broken up by little

islands and at its narrowest was about 350 yards

across. The Chasseurs estimated that it would take

John 3-4 hours to mount a concerted attack on the

fords at Priula and San Nichiol.

The Archduke was centred on Conegliano

some 8 miles from the furthest of the three fords on

the eastern bank of the Piave. The terrain between

was flat, crossed by dikes and streams, and the 8eme

Chasseurs who had been sent to scout ahead reported

that if the crossing was made in the early morning

when the river was low it could be accomplished.

The river all along this section is broken up by little

islands and at its narrowest was about 350 yards

across. The Chasseurs estimated that it would take

John 3-4 hours to mount a concerted attack on the

fords at Priula and San Nichiol.

With this information, Eugene concluded that John did not intend to seriously defend the river line, but rather intended a further withdrawal. He was right. John knew that the Piave rose during the day, and he firmly believed that Eugene would not risk such a dangerous crossing with the Austrians in the neighbourhood. He also believed that having evaded Eugene before, he could do it again.

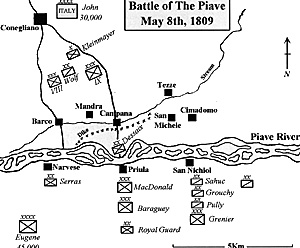

Eugene, however, was not the faint-heart that John was. Realising that he would need two fords to get all his troops across, he did not hesitate. He would cross at San Nichiol and Priula. At San Nichiol, Grenier would cross. At Priula, Dessaix would lead off, followed by Macdonald and then Baraguey. The Royal Guard would remain in reserve whilst Serras' division would make a feint at the third ford at Narvese. It was intended to speed up the Priula crossing by throwing across a pontoon, protected by Sorbier's artillery.

The Battle Starts

The whole plan kicked into gear at dawn on May 8th, and the gunfire which drove away the light Austrian ford guard quickly woke up John and his troops. He knew he was in heap big trouble. Knowing that with his cumbersome supply train a rearguard would almost certainly be annihilated, John decided on the only sensible course of action; namely to attack. He reasoned that with a bit of luck he could drive the French back into the river. Sadly what happened was an attack in installments.

The cavalry led off, but instead of going to the ford at San Nichiol where most of Eugene's horse were crossing, they moved in the main against Dessaix and the sounds of gunfire. The single hussar regiment moved to San Nichiol with Kalnassy's infantry bngade was incapable of stopping the flow of French troops. Meanwhile, Dessaix had got his whole division over in under an hour and was already in position to cover Macdonald's crossing. The engineers had just begun building their bridge when Wolfskehl's cavalry arrived. Their 24 guns began firing at Dessaix, but the range was close to a 1000 yards and impatient with their effect, Wolfskehl ordered an attack. Without infantry, and with no close range guns, Dessaix was in little danger. His voltigeurs rapidly went into square and Wolfskehl broke against them.

Eugene then ordered Macdonald to get his own artillery across first, and a nasty counter battery bombardment began, as Eugene attempted to clear the way for a safe crossing. This time everything went right. At Sacile, in his first battle, Eugene's timing had been way off, but today everything feel into place. Sahuc and Pully arrived from the other ford with their cavalry to strengthen Dessaix. Eugene wanted to destroy Wolfskehl's cavalry before it could recover itself from the foolish attack on Dessaix, and before infantry reinforcements arrived. He ordered Sahuc and Pully to attack on both flanks of the Austrians, whilst the artillery pounded their front. It worked beautifully.

In the ensuing melee, Wolfskehl was killed and his second-in-command captured. The Austrian cavalry fled, utterly routed, and the victorious French charged the guns, capturing 14 of them and fatally wounding Reisner, the artillery general. Not content, they then set off in pursuit of the beaten Austrian horsemen.

The French cavalry quickly came up on the Austrian VIII Corps and IX Corps deploying around Mandra and Campana, and unlike Wolfskehl they sensibly pulled up, out of range. Nevertheless, the cavalry charge had been the decisive moment in the battle. It forced John to deploy his infantry behind the dike to protect them from the now unmolested French dragoons who roamed the field looking for easy pickings. It also meant that Eugene could cross untouched.

However, if the Austrians were proving little opposition, the Piave at least was flexing her muscles. The speed and level of the river had gradually increased, until at 3:00 PM Eugene had to stop further crossings. He had about 30000 men across, consisting of Dessaix, along with Lamarques', Broussier's and Abbe's infantry divisions, and Grouchy's, Sahuc's and Pully's cavalry. The troops facing each other were just about equal, less John's lack of cavalry, of course.

It was clear to Eugene that John, to prevent being outflanked, had strung his line out extremely thinly, and that he - Eugene - could concentrate his men to attack at any point he chose, thus gaining a battlefield superiority. Napoleon would have been justly proud. Indeed, it was almost too easy. Given as much space and time as he needed, Eugene capably drew up his forces. Dessaix and Sahuc were lined up against VIII Corps to the west. Macdonald was in the centre against IX Corps. Grenier was on the right, commanding Abbe's infantry and Grouchy's and Pully's dragoons, against the villages of San Michele and Cimadolmo, in which Kalnassy's exposed brigade must have felt most uncomfortable.

Masse de Manoeuvre and Masse de Rupture

Eugene planned to use Grenier as the Masse de Manoeuvre and Macdonald as the Masse de Rupture, as taught to him by the master. Grenier would clear out Kalnassy and then turn John's left wing, obliging either a weakening of the centre or a retreat. At that moment Macdonald would attack.

Grenier went in at 4:00 PM, but despite a solid defence, Kalnassy, outnumbered two-to-one, was driven out, leaving over 1000 men behind. Sorbier's 24 guns, lined up in front of Macdonald, then began a savage bombardment on IX corps. The resulting confusion in the Austrian ranks was clear for all to see, and Eugene ordered Macdonald to charge. The Austrians quickly broke, and John sent in his only reserves, Kleinmayer's grenadiers, who were simply overrun. The collapse of the centre obhged VIII Corps to pull back to avoid being cut off.

Had Eugene been John, the Austrians probably would have got away, but he as not. Sensing the moment, he ordered a vigorous pursuit, only halting at 8:30 PM as night was falling.

John' s shattered army did not stop. They pressed on throughout the dark hours towards Livenza and ironically reached Sacile the following morning where they began regrouping. Frimont was left with another rearguard and the retreat continued.

The victory was all that Eugene could have hoped for. Some 2000 Austrians lay dead and another 3000 had given up their arms. Another 2000 were fugitives of no combat value to the distant John, and whom Eugene could corral at his own pleasure. The French losses were less than 2000 all told.

The effect of the battle was to transform the balance of the war in Italy. John was now incapable of offensive action, and a newly confident Eugene held the initiative. The Viceroy had buried the memory of Sacile and proved the lingering belief that he could command troops.

Macdonald of course tried to steal the glory for himself,. In his memoirs he suggests that it was really himself who was in command and that Eugene was bordering on panic before Macdonald calmed him down. Different independent accounts, including one by Caffarelli do not support these lies. Macdonald had no control over any troops but his own, and his spurious claims hold far less water than the river he crossed. The fact that Pelet and subsequently Petre have supported Macdonald's views has, I believe, been dismissed in issue 28.

Wargaming The Battle 0f The Piave

The "Eugene Trilogy"

Part 1: Battle of Sacile

Part 3: Battle of Raab

Related article:

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #30

© Copyright 1996 by First Empire.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com