In the last issue, part 2 of the trilogy concerning the 1809 Italian campaign of Prince Eugene de Beauharnais, we saw how the young viceroy turned the tables on the Archduke John, inflicting defeat on the Austrians on the banks of the Piave River, on May 8th, 1809.

Unlike the delay which followed the Austrian victory at Sacile, Eugene began following up his defeated opponent at dawn the following morning. Eugene sent Grouchy with all three cavalry divisions out ahead, followed by Dessaix's elite advanced guard composed of voltigeurs. This was fairly bold, considering that in the meantime engineers were throwing up a bridge at Priula to bring the rest of the French troops across.

As Grouchy crossed the field he discovered more and more Austrian casualties, and clear signs that the retreat was being carried out in some haste. Further, he began picking up numerous Austrian stragglers who had lost the stomach for continuing. Things clearly did not bode well for the Archduke.

That same day Napoleon's fresh orders reached his stepson. Dated May 1st, the Emperor advised Eugene that he was manhandling the Austrians back on Vienna and instructing the Viceroy to keenly pursue the Archduke John. Further, Eugene was charged with reinforcing Napoleon before Vienna as soon as John was dealt with, where the combined forces would sort out the Archduke Charles. The link up was expected to take place at Bruck, via an invasion into Carinthia.

Sacile II

Ironically the pursuing French caught the Austrian rearguard in Sacile, a stone's throw from the scene of the earlier defeat. Frimont's weary troops put up little fight before retreating towards their main body at Saint Daniel, followed within a day's march by Eugene, who attacked Frimont there on May 11th, nearly encircling the 4000 Austrians and inflicting close on 50% casualties. From then on Frimont was little more than a delaying force, incapable of a thorough defence, and when they followed John out of Italy and into Carinthia, there were less than 20000 men under the white and yellow banners. This force was soon further weakened by 5000 men when IX Corps was detached to reinforce Carniola, with the intention of buying time for more troops to be raised.

John now found his own position desperate. He had no more than 14000 men to fight off Eugene's 40000 troops. He decided to retire on Graz, via Klagenfurt, to protect the mobilising of the Hungarian Insurrection. With Chasteler and Jellachich ordered across from the Tyrol, John estimated that he could effectively double his own numbers, giving him a fighting chance.

In the meantime, fearing being bogged down in the Alpine passes, Eugene split Rusca's division was ordered to cross into Carinthia through the Gailitz valley, the intention being to force John to further weaken his troops. To this end Serras was also detached on a third route, leaving the viceroy with a force of about 25000 men, with another 11000 in the detached formations; speaking of which, Macdonald's corps was ordered to seize Laibach and upset the Croatian Levy, thus protecting Eugene's right flank.

The hard fighting which the next week brought was carried out with a high degree of panache and style. The Austrian garrisons blocking the advance were either outmanoeuvred or squashed and on May 20th Eugene was in Klagenfurt, where he had to order a halt to allow his artillery to catch up. At this time Dessaix's advance guard formation was broken up, with its commander being given a brigade under Durutte.

Back in the Austrian Camp

Back in the Austrian camp, John was, as usual, having problems. Chasteler had come off second best in an engagement with Lefebvre's VII Corps at Worgel, and the Tyroleans were in check. Schmidt's brigade from Frimont marched into camp with only 50% of the 3000 troops armed.

Further instructions from Napoleon urged Eugene to get to Bruck with as much strength as possible, and accordingly Grouchy and Macdonald were ordered to converge on Graz. These movements were begun with commendable rapidity, and one unexpected bonus was that Eugene surprised Jellachich on his way to join John in Hungary at Saint Michael and of the 8000 whitecoats that marched onto the field, only 1500 ever got to join up with the Archduke. In contrast, the following day Eugene marched into Bruck, making contact with the Emperor's outposts. He expected to be joined there on June 1st by Grouchy and Macdonald, so he settled down for a well-earned rest. Then, on May 29th, he rode to see the Emperor.

Napoleon and the Archduke Charles were eyeing each other up from opposite banks of the Danube. With similar numbers, neither held a decisive advantage, and both had been relying on the victors of the Italian campaign to weigh the balance. This was particularly true for napoleon, who had received a sharp reverse at Aspern-Essling. However, until John's army, now in Hungary, could be fully crushed, Napoleon felt unable to devote his full attention to the Danube.

The Archduke John commanded about 38000 men, but they were scattered over a distance of about 150 miles. Nevertheless they represented quite a threat , should they unite, and potentially they were also in a position to directly reinforce Charles, thus making Eugene's presence indecisive. Thus once more Napoleon sent Eugene after the Archduke John.

Eugene rejoined his forces at Neustadt on June 2nd. There were 30000 troops on hand, with only Macdonald absent. That worthy's corps was besieging Graz, and was directed to leave Broussier to cover the fortress and to return with his remaining troops. In addition, a mixed division under Lauriston helped make up the numbers.

Information came into Eugene's possession suggesting that John was concentrating at Raab. Being now directly under the Emperor's command, the Viceroy of Italy reported at once suggesting that he immediately advance on the town. On June 6th he received strict orders from Napoleon to move on Kormend, which would hook around and behind John. Further welcome reinforcements arrived in the shape of a division of light cavalry under Montbrun. The tone of the Emperor's orders must have stung Eugene. They were critical, at times almost derogatory, and it is clear that Napoleon had not yet forgotten or forgiven Sacile.

This pain may have been eased when fresh reports confirmed John to still be at Kormend, but that as yet he had not been reinforced by either Chasteler or Giulay's IX Corps. Accordingly Eugene advanced on Kormend, hoping to catch John before he could be strengthened. This never happened. Hearing of the advance, and knowing himself outnumbered, John fell back on the town of Papa. With all the movement and counter-movement going on, both sides temporarily lost each other, and Eugene sent Grouchy out to find the Austrians.

Austrians Found

They turned up near Papa on June 11th, and Eugene at once ordered a rapid advance, despite the fact that Macdonald had not caught up. That general was ordered up as quickly as possible. Any expected fight at Papa (not an appropriate name for a battle, anyway) failed to materialise as John once more got wind of Eugene and retired on Raab, although Papa was graced with a fair degree of Austrian blood as Grouchy's cavalry polished off the mounted rearguard with some aplomb.

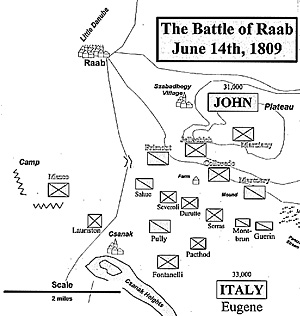

On June 13th John arrived at Raab. He now commanded 17500 infantry and 3000 cavalry. He there tied up with the Archduke Joseph who held a fortified camp garrisoned by 65000 infantry and 4000 cavalry. Of these troops, nearly half were landwehr and general levies. The town of Raab itself sits at the confluence of three rivers, the Little Danube, the Raab, and the Rabnitz, and Joseph's entrenched camp was between the Rabnitz and the Raab rivers.

At Raab, John received orders to detach 8000 men to Charles, something which cannot have filled him with enthusiasm. Already Eugene's scouts were in sight, and he had a hurried decision to make. This time, he chose to fight. Believing Raab to be important, he also chose to remain south of the rivers. He decided to seize the Csanak Heights and using the ridge as a dominant artillery position, force Eugene to attack at great cost. This would also help make up for his troops inferior experience. There were already four battalions on the ridge, but by the time John had comer to his decision, they were no longer in residence, having been swept away by Grouchy's cavalry, with Eugene himself at their head. Grouchy then charged the reinforcements sent by John and he delayed them until Durutte and Lauriston had secured the ridge.

Both sides then broke off, each wanting the other to attack. John was inept, but he wasn't a fool, and he knew that his mixed bag of troops would likely get a good mauling if they tried to storm the Csanak Heights, so accordingly he pulled back on the Szabadhegy Plateau, itself an excellent all round defensive position. Things then settled down for the following morning's showdown.

Pre-Battle Preparation

John had 43 battalions on and around the plateau, supported by 66 cavalry squadrons. He had dispensed with his old corps, instead combining the regular and landwehr troops into divisions of two or three brigades. These were commanded by Marziany, Colloredo and Jellachich. Their dispositions can be seen on the map. Archduke Joseph and Generalmajor Meczery had 40 squadrons covering the left, with the remainder under Frimont to the right. Mezko, holding the camp, commanded just 5 battalions and 6 squadrons.

Meanwhile, Eugene settled his troops on the Csanak. He was hoping to be joined by Macdonald, but that gentleman had chosen to camp at Papa, and the messenger spent fruitless hours attempting to find the general, who had clearly decided to take in the town. Once found, Macdonald despatched Pully's cavalry, who arrived before dawn. The infantry, however, would play little part. The morning of June 14th illuminated to show Eugene that John had little intention of conveniently attacking. The onus was on the viceroy, and both sides knew it.

The advancing French were in two ranks of battalion columns, and heavily screened by skirmishers. This manoeuvre quickly slowed under the detrimental effects of the Pancza Brook, which proved boggy and far more treacherous than it had appeared from a distance. This particularly effected Grouchy's troopers, who were unable to cross and had attracted the unwelcome attention of the Austrian artillery. It was beginning to look like a re-run of Sacile.

This time Eugene learnt from his mistake. Instead of reinforcing the stalled attack, as he had done before, he ordered a full frontal assault along the whole line, believing that in a battle of attrition the Austrians' large number of raw troops would come off second. The reserve could then be committed to gain victory.

The three attacking infantry divisions, Severoli, Durutte and Serras went in as Grouchy finally crossed the brook and with the aid of well used horse artillery got the better of Meczery. This uncovered Colloredo's flank, and he was obliged to abandon the mound in the middle of his position which was acting as a very efficient strongpoint. This enabled the struggling French infantry to re-new their assault on John's centre.

Kiesmegyer Farm

The climax of the battle centred on the Kismegyer Farm, which anchored the middle of the Austrian line. Recognising its importance, John reinforced it with six battalions. These troops swept out and drove Severoli and Durutte back towards the brook in disorder. John should have reinforced this attack, but he missed his opportunity, and Severoli's Italians rallied gamely and spearheaded the counter-attack which drove Jellachich back, allowing Serras to take the farm. Marziany, who at one stage probably imagined himself leading the reserve to glory now found himself as a rearguard. He did his job well, covering the other tow broken divisions as they retreated However the cost was high. Surrounded by cavalry, a number of whitecoated squares were broken by cavalry and Marziany was captured.

The nature of the terrain, the lateness of the day, and the disorder of the French cavalry meant that Marziany's sacrifice was not in vain, and the remnants of Johns army escaped under cover of darkness. The Austrians counted 6000 casualties, killed or captured, against 2500 French. Eugene had guessed correctly, and won the battle of attrition.

Raab cannot be considered a great success for Prince Eugene. Admittedly it was not his own fault. Napoleon's orders were explicit and stated that Macdonald's troops were not to be used until fully fresh, which clearly they were not. The frontal attack which developed was also unimaginative, although his plan was sound based on the information available to him.

Strategically, Eugene was not totally successful. John was still able to join Charles, although in a much decreased condition, and he was separated from Chasteler and Giulay. The 13000 men which John led to Wagram were too few and too late to prevent their defeat, where Eugene and his Army of Italy fought with distinction.

The "Eugene Trilogy"

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Eugene now commanded 33000 men, but he thought that John had upwards of 40000 available, although a large proportion was believed to be of inferior quality. Accordingly, a right hook was planned, with the aim of trapping him against the Little Danube. The attacking wing would consist of Grouchy and Grenier, the former to clear the cavalry, and the latter to storm the plateau. On Eugene's left, the less-capable Baraguey d'Hilliers had the passive role, with Lauriston on the far left screening the camp. The attack began at noon.

Eugene now commanded 33000 men, but he thought that John had upwards of 40000 available, although a large proportion was believed to be of inferior quality. Accordingly, a right hook was planned, with the aim of trapping him against the Little Danube. The attacking wing would consist of Grouchy and Grenier, the former to clear the cavalry, and the latter to storm the plateau. On Eugene's left, the less-capable Baraguey d'Hilliers had the passive role, with Lauriston on the far left screening the camp. The attack began at noon.

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #31

© Copyright 1996 by First Empire.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com