Tolentino: The First Day

Murat's intentions on the 2nd are unclear, but he apparently only planned a 'necessary reconnaissance of the Austrian positions', hoping that a limited advance would suffice to push Bianchi out of his position.

This would help explain why he only employed a portion of his army on the first day of the battle. Leaving the Guard infantry and four of d'Ambrosio's battalions in Macerata as a reserve, he formed two principal columns of attack with his remaining troops: nine squadrons of Guard cavalry, d'Ambrosio's other eight battalions and the 10th Line.

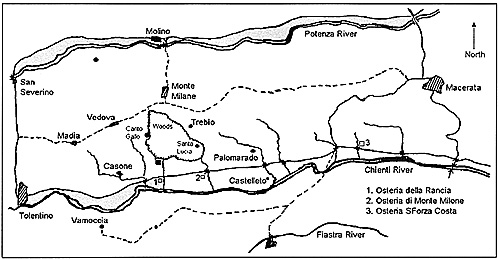

The left column (Generals Livron and Campana), composed of the cavalry, most of the guns and some infantry, would advance up the Chienti valley while the right, infantry and some guns under the capable d'Ambrosio, moved on Monte Milone. Two small infantry columns would serve to connect the principal forces.

As for the rest of the army, Lechi was to bring seven of his battalions and his cavalry to Macerata, leaving behind five battalions as a support for Carascosa who would continue to contain Neipperg. Although his men had been in position since the previous day, Murat was slow to move and the attack columns did not begin until late morning.

Almost Captured

The left column, moving down the road from Macerata to Osteria Sforza Costa, encountered Bianchi's vedettes around 11:30 a.m. and pushed them back, capturing a detachment of Jagers and nearly taking Bianchi as well. Fortunately for the Austrian commander, a squadron of hussars quickly pounded up to extricate both him and the hapless Jagers. In the valley, the Habsburg hussars scored another success when three squadrons repulsed the leading six squadrons of the Neapolitan left column at the first bridge west of Sfona Costa. But this little victory was temporary. The Neapolitan cavalry rallied on its approaching infantry and Starhemberg withdrew behind the small stream running from Castelleto to Palomaredo.

Before long, pressed by active Neapolitan skirmishers, he was falling back again, this time to the line Monte Milone to Trebio to Osteria Monte Milone. The Austrian infantry repulsed the 3rd Light's courageous efforts to storm the heights around Santa Lucia, but were compelled to retire as d'Ambrosio's column made progress toward Monte Milone.

Loss of Santa Lucia

The loss of Santa Lucia also forced Starhemberg's men in the valley to withdraw and they established themselves at a new position near the Osteria della Rancia. The Neapolitan cavalry pursued vigorously, however, surrounding and capturing the trail company (from Simbschen) of the Austrian rear guard.

Ordered to hold his ground but with no additional support, Starhemberg committed his last reserve to the line, his company of pioneers. Fortunately for Bianchi, Starhemberg was able to hold the Neapolitan left column in check and the fight in this portion of the battlefield settled into an exchange of musketry and artillery fire.

On the Neapolitan right, d'Ambrosio's men, encouraged by the presence of their monarch, had by now occupied Monte Milone and were preparing to continue their advance. The Austrians performed well, but the weight of numbers gradually forced them back across the open, rolling heights of Canto Gallo toward their main positions between Casone and Madia. Bianchi, however, had no intention of allowing the enemy to bivouac so close to the heart of his defence and, at about 5 p.m., he ordered GM Senitzer to push the Neapolitans back behind Vedova.

Unfortunately for Murat, d'Ambrosio was badly wounded at about this time and had to turn over his command to the irresolute and incompetent Luigi d'Antonio. As a result, Senitzer, advancing across the meadows in splendid form at the head of four battalions, found that the Neapolitans withdrew quickly before him, offering almost no resistance. As evening drew on, the Austrians were thus able to clear the heights of enemy troops, leaving d'Aquino to collect his somewhat disordered men in the woods south of Monte Milone. Bianchi, satisfied with the retreat of the Neapolitans, left a chain of pickets opposite the woods and quietly withdrew Senitzer's men to the main position around Madia during the night.

Satisfied

Curiously, Murat too seems to have been satisfied with the day's action. He should not have been. Whereas Bianchi had held his own, Murat had failed to exploit his numerical advantage or to press home his potentially successful attacks. The king had displayed his old ardour and energy; he seemed to be everywhere on the field, inspiring his men, rallying them and leading them forward. Though mercurial in mood, the men had done well, showing themselves courageous and occasionally enthusiastic if susceptible to sudden and drastic discouragements; the Austrian reports were unanimous in praising the bravery of Murat's soldiers on the first day of the battle.

Neapolitan leadership, on the other hand, was generally weak, as exemplified by d'Aquino's inexcusable behaviour. Moreover, the king's activity was local in effect. He could rouse a battalion for another charge but could not provide the grand tactical direction or energy necessary to crush Bianchi or even to push him out of his position. His subordinates were incapable of filling the resultant gap.

Tolentino: The Second Day

Murat's plan for 3 May foresaw a general attack by three different columns. In the centre, General Pignatelli-Strongoli would drive on Casone with the infantry and cavalry of the Guard, the 10th Line and practically all of the Neapolitan artillery. Murat hoped that the pressure created by Pignatelli-Strongoli's advance would force Bianchi to commit his reserves and portions of the Austrian left wing to the Chienti valley.

As Bianchi weakened his left, d'Aquino, reinforced on his right by Lechi with General Ignazio Caraffa's Brigade, would debouch from the woods and roll up the Habsburg troops in the Madia position. Four battalions and two squadrons from Lechi's Division would form a third column under General Luigi de Major they would cross the Chienti, brush aside the Austrians at Vamoccio and attack Tolentino from the south to cut off Bianchi's line of retreat.

Covered by a dense morning fog, Murat's troops assembled in the Chienti valley and began their advance: infantry to the north and south, Guard cavalry along the highway in the centre. Despite the determined resistance of the Austrian defenders, the attack made progress. Before long, Neapolitan batteries were established west of Osteria della Rancia along the edge of the Casone stream and, most important, Guard infantry was able to push through Guiboli to seize Casone itself. It was time for d'Aquino to launch the decisive assault and Murat at Casone sent repeated orders directing the new commander of the 2nd Division to advance.

Scattered

D'Aquino's men, however, were scattered all over the countryside foraging for the victuals which the commissaries had neglected to provide and he thus contented himself with sending forward some skirmishers to harass the retiring Austrians and one battalion of the 2nd Line to hold Vedova. The rest of the division remained in the woods. These dispositions invited counterattack and Bianchi quickly obliged.

While Oberst Paumgarten led forward Regiment Chasteler to scatter the Neapolitan skirmishers, the lone available squadron of dragoons was ordered to charge their supports, the battalion of the 2nd Line. The unfortunate men of the 2nd Line had no time to form square before the cavalry was upon them and in moments, both they and the skirmishers were either sabred, captured or dispersed. D'Aquino was too distant and too disorganised to help and two squadrons sent by the furious Murat were delayed by some marshy ground.

Despite this setback for the Neapolitans, Murat's situation was still good. It was about noon, all of Bianchi's troops (except Eckhardt's small detachment) were committed, the Neapolitan Guard held Casone, and most of d'Aquino's and Lechi's troops had not yet entered into the fight. The king redoubled his efforts to get d'Aquino moving (oddly, he neither relieved his inept subordinate nor took control of the attack himself).

Unfortunately, when d'Aquino finally did advance, he did so in the worst formation imaginable. Evidently terrified that more of his command would suffer the fate of the skirmishers and 2nd Line, d'Aquino formed his division into four large squares and ordered them forward across the broken ground between the forest and Madia. Just when the situation demanded a rapid attack in a flexible formation, he selected one which was slow to form and slower to move.

Echeloned from the right with three squares in the first line followed by the fourth, the unwieldy masses made their painful way across the Canto Gallo, raked by Austrian artillery and musket fire despite support from some of Murat's guns over by Casone. Hit hardest by the Austrian lead and iron, the first square (that on the right front) began to waver and Bianchi, judging his moment nicely, launched two newly-arrived squadrons of dragoons against its right flank while three infantry battalions (two from Chasteler, one from Wacquant) advanced to attack the other squares.

The shaken Neapolitans did not await the dragoons' charge. Despite the efforts of their officers, the men of the first square turned and fled across the hills to the forest; their panicked flight infected the second square as well, and it too broke without actually coming into contact with the Austrian attackers. Only the third square (2nd Line), inspired by Murat who had sped across the meadows with a tiny escort, held together and retreated in good order. Reaching the edge of the wood, it joined the fourth square and deployed into line of battle to protect the shattered battalions of the first two squares.

Fortunately for Murat, Baron Taxis at the head of the Austrian dragoons, took a roundabout route in his pursuit and got bogged down in some wet ground. By the time he and his troopers had extricated themselves, it was too late to turn the disordered Neapolitan withdrawal into a rout. As Weil points out, had Taxis taken a straight course, the entire 2nd Division might have collapsed and Murat, his right in ruins and his centre compromised, would have had to break off action shortly after noon. As it was, the king would need every moment to reform his right because a new danger was now threatening from Monte Milone.

New Danger

GM Eckhardt, following Bianchi's instructions, had moved from San Severino to Molini with his small detachment and was now approaching Monte Milone. Murat, however, quickly sent two rallied battalions to hold the town, and these troops not only succeeded in repelling two attacks by Eckhardt but also remained masters of this critical position for the rest of the afternoon.

To Murat's frustration, this small success was followed by another reverse. The retreat of the 2nd Division gave Mohr an opportunity to recover Casone and after a brief, hot struggle, the Austrians were again in possession of this key point. Furthermore, Majo's feeble effort to seize Vamoccio and threaten Bianchi's rear had faltered and his detachment remained stalled in front of the little village.

This series of setbacks evidently unnerved Murat and, although his army was by no means beaten, he concluded that the battle was lost and decided to retreat on Macerata as soon as nightfall would allow a safe disengagement. Unfortunately, when his chief of staff, Millet, prepared the written orders for the withdrawal, he inserted the word 'immediately', setting in train a chain of disasters that would culminate in the complete dissolution of the Neapolitan Army.

Millet soon recognised his error, but the damage had been done. On receipt of the written order, General Pignatelli-Strongoli directed his men to pull back, giving little apparent thought to the details of the withdrawal or the overall battle situation. His officers pleaded with him to appeal the order, a staff officer from army headquarters brought verbal confirmation of the mistake in timing - all to no avail.

The stubborn general stuck to his decision and rode off to Macerata, leaving his troops to retreat as best they could. Murat too had gone back to Macerata and Millet, although in a position to witness the impending catastrophe, did not make the short ride to Pignatelli-Strongoli's position to correct matters. The Neapolitan cavalry held together but the withdrawing infantry soon became a disordered mob.

With his foe clearly wavering, Bianchi ordered his men to advance and they were soon pressing the crumbling Neapolitan army back in all sectors. Even south of the river, where Majo outnumbered the Austrians, the poorly-led Neapolitan units gradually began to lose their cohesion as the afternoon slid towards evening.

Rear Guard

Fortunately, the rear guard at Monte Milone kept up a tenacious defence, holding off Taxis and Eckhardt until the fall of night. By evening, other than a small blocking force at Sforza Costa and the rear guard falling back along the road from Monte Milone, the Neapolitan Army, more by accident than design, was clustered around Macerata in a confused, nearly leaderless, tangle. Demoralised, poorly-supplied and exhausted from the day's long battle under a hot sun, the huddled soldiers were made yet more miserable by a violent, drenching rainstorm.

At an impromptu conference, Murat received only lugubrious news from his feeble and insubordinate collection of generals. Pignatelli-Strongoli, d'Aquino and Lechi all reported that their divisions had disintegrated or that the few remaining troops were in such a state of discouragement that they were likely to throw down their arms and flee at the first sight of the Austrians.

These dark appraisals, though exaggerated, depressed Murat and, instead of relieving his negligent division commanders, he grew irresolute and indecisive. The squabbling among the generals as each attempted to justify his own behaviour and castigate his comrades, could only have increased the king's dolour.

In short, Murat decided that the army would abandon the good road through Tolentino, link with Carascosa's Division and continue its wretched retreat to Naples along the poor byways south of Ancona. Caraffa's Brigade, which had sat idle in Macerata throughout the day, was sent to the southeast with a chevauxlegers regiment to secure the route of passage.

End of the Realm

More Tolentino

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #16

Back to First Empire List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by First Empire.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com