American offensive operations in the Central Theater for 1813 ended with the twin disasters at Chateauguay and Crysler's Farm. The seed for these defeats was planted when Secretary of War John Armstrong ordered James Wilkinson, newly promoted to major general, to depart his command in New Orleans and take command of the Ninth Military District from Henry Dearborn. Dearborn was relegated to a quiet command in New York City. Armstrong erred in appointing Wilkinson, an inveterate intriguer, to this crucial command. Wilkinson did not enjoy the confidence of all his officers and the mutual loathing he shared with Major General Wade Hampton was no secret in the Army. Hampton, a legitimate hero of the Revolution, commanded the forces on Lake Champlain and would be expected to cooperate with Wilkinson to some degree in any operations that Armstrong devised.

American Strategy

The inability of Dearborn to parlay the capture of Fort George in May into gains of strategic dimension caused Armstrong to rethink his strategy. Armstrong concluded that severing the British line of communication between Kingston and Montreal would be decisive to the war effort. On 23 July, Armstrong gave his new commander a choice of two courses of action. First he proposed a main attack against Kingston with a secondary attack against Montreal. This might provoke Prevost to withdraw troops from Kingston to defend Montreal. The second option was a two-pronged attack on Montreal with one force originating at Plattsburg and the other from Sackett's Harbor. This would cut the supply lines to Kingston in short order.

Armstrong joined Wilkinson at Sackett's Harbor and with Commodore Isaac Chauncey they tried repeatedly to hammer out a plan. Armstrong had a secondary mission of coordinating the efforts of Hampton, who had offered his resignation rather than serve under Wilkinson. Hampton was sufficiently appeased by Armstrong to remain in command until after the campaign ended and by late September Hampton’s army of inexperienced recruits was poised on the border waiting for the signal to advance on Montreal. In mid October, Wilkinson issued orders for his army to move to Grenadier Island where Lake Ontario tapers into the St. Lawrence River. His subordinate commanders and Hampton were still unsure, as was perhaps Wilkinson himself, whether they were moving on Kingston or Montreal.

Hampton Advances

Having received orders to move from Armstrong, Hampton advanced down the Chateauguay River on 21 October with four thousand troops and Brigadier General George Izard as his second in command. Nearly all of the fourteen hundred New York militia with him had refused to cross the border. A month earlier, Sir George Prevost had called out eight thousand Lower Canada militia to block the path to Montreal. The militiamen, mostly francophone, had responded quite well. They were drilled in the rudiments of soldiering and adequately armed. Their immediate commander was that light infantry veteran, Lieutenant Colonel Charles de Salaberry, commander of the Voltigeurs. De Salaberry had his men drop logs across the cart path which paralleled the river. Hampton’s advance guard was continually being sniped at by Indians and Canadians.

The Battlefield

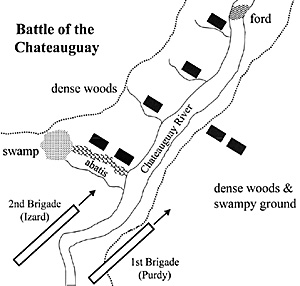

On October 25th, Hampton drew up to a series of barricades and abatis blocking his way. By interviewing the locals, Hampton learned that there were essentially five defensive lines stretching nearly two miles along the river. The route through the British position was the road through a fairly dense forest. Hampton needed the road open to move his guns and supplies. Each defensive line was a breastwork of dirt and timber built along a stream emptying into the river. The stream bed served as a ditch which strengthened the defensive value of the breastwork. The first defensive line was also further strengthened by an abatis which extended from the river’s edge to a swamp several hundred yards into the forest.

On October 25th, Hampton drew up to a series of barricades and abatis blocking his way. By interviewing the locals, Hampton learned that there were essentially five defensive lines stretching nearly two miles along the river. The route through the British position was the road through a fairly dense forest. Hampton needed the road open to move his guns and supplies. Each defensive line was a breastwork of dirt and timber built along a stream emptying into the river. The stream bed served as a ditch which strengthened the defensive value of the breastwork. The first defensive line was also further strengthened by an abatis which extended from the river’s edge to a swamp several hundred yards into the forest.

American Order of Battle - Hampton’s Division

First Brigade commanded by Colonel Robert Purdy

- Light Infantry Corps (350)

4th Infantry (600)

33rd Infantry (300)

Maine and New Hampshire Volunteers (400)

Second Brigade commanded by Brigadier General George Izard

- 10th Infantry (250)

11th/29th Infantry (750)

30th/31st Infantry (700)

Cavalry 150 organized in 2 companies

Artillery 8 six-pound guns and 1 howitzer organized in three companies

The Light Infantry Corps was an ad hoc formation of the light companies from all the infantry regiments. The Maine and New Hampshire Volunteers were separate organizations consolidated for this campaign. Likewise, four regiments in the Second Brigade were consolidated into two maneuver units.

British Order of Battle

British forces consisted of several types. The Canadian Fencibles [red coats faced yellow] were trained and equipped as regulars. The Voltigeurs [distinctive gray uniforms faced black] were likewise trained and equipped. Two types of militia were represented. The Sedentary Militia consisted of all males, 16 to 60. They were not uniformed but were equipped and rudimentarily trained. The Select Embodied Militia [SEM] were volunteers or conscripts serving for at least a year. They were armed, trained, equipped, and uniformed as regulars. De Salaberry was backed up by “Red George” Macdonell of the Glengarry Light Infantry Fencibles who at the time of the battle was commanding a light battalion of SEM. While De Salaberry commanded at the first defensive line, Macdonell commanded forces in the rearward lines.

De Salaberry

- Light Company Canadian Fencibles (70)

Two companies Voltigeurs (100)

Two companies SEM (140)

Two companies Sedentary Militia (80)

Indians (22)

Macdonell

- Two companies Voltigeurs (120)

2nd Battalion SEM (550)

5th Battalion SEM (150)

Boucherville Sedentary Militia (250)

Indians (150)

Hampton’s Plan

Hampton understood that a direct assault through the strong British position would be costly. He learned that there was a well-established ford across the Chateauguay located immediately behind the last defensive line. Hampton chose a risky strategy which, if successful, would turn the entire defensive line. Hampton ordered Purdy to take his brigade across to the right bank of the river and move directly to the ford. Crossing at the ford, Purdy would trap the defenders between himself and Hampton. When Hampton heard the firing coming from the distant ford, he would send Izard and his brigade into a frontal attack on the first defensive line. Caught between two fires, the Canadians and Indians be provoked into retreating into the woods or remain to be captured.

The plan came unraveled almost from the beginning. After sunset and in a rainfall, Purdy took his men on a long march through the woods and bogs on the right (eastern) bank of the river. In the dark, the local guides got lost and Purdy’s men stumbled about trying their best to move toward the ford. Meanwhile, back at Hamton’s headquarters, he received a letter which instructed him to construct winter quarters on the American side of the border. Apparently Secretary of War Armstrong wasn’t serious about the campaign. Shaken, Hampton could not recall Purdy and therefore decided to continue the attack.

Hampton ordered Izard to occupy the British forces in the first defensive line to draw their attention away from Purdy who supposedly would be at the ford soon. Izard brought the 10th Infantry forward toward the abatis. De Salaberry had the company of Canadian Fencibles and a company of Voltigeurs behind the abatis, the Indians in the woods on his right, and two other companies in immediate reserve. Meanwhile Macdonell sent a company of SEM and one of sedentary militia across the river at the ford in order to secure it.

The Battle

With some difficulty, Izard deployed the 10th in line and marched them up to the ravine where they opened a brisk fire on de Salaberry’s men behind the abatis. The 10th kept this up until they ran low on ammunition. On the opposite side of the river, Purdy heard the firing and oriented his men to move forward. He sent out an advance guard of two companies to feel their way through the thick woods. This advance guard ran into some Indians and a company of sedentary militia. The two sides opened fire and sustained the firefight for perhaps fifteen minutes. With visibility very poor indeed, both sides believed they were outnumbered and both withdrew. The Canadian militia fell back upon a company of select embodied militia and both companies cautiously moved forward to reestablish contact with the Americans. Purdy received exaggerated reports from his advance guard and then received an order from Hampton to break off the attack and return to the other side of the river. Purdy pulled his men together as best he could in preparation for a withdrawal. Meanwhile Izard brought up his entire brigade to support the 10th Infantry in front of de Salaberry's line.

Izard formed his three battalions into line and advanced on the British position. De Salaberry posted a skirmish line of three companies in front of the abatis. The Americans standing shoulder to shoulder fired in volleys at the Canadians who were hiding behind trees and rocks and firing independently. The Canadian fire was quite accurate but could not prevail against the sheer volume of the American musketry. De Salaberry pulled his skirmishers back behind the abatis and Izard advanced. The intense firefight resumed. Soon the Canadians sent their Indian allies into the woods on the western side of the fight along with several buglers blowing a charge. To Izard, the signs were ominous; the British were beginning to outflank the Americans on their left.

Meanwhile, on the opposite sides of the river, the two Canadian companies made contact with Purdy's much larger force in the woods and opened a brisk fire which the Americans returned. Neither side knew the strength of the other. Eventually the Canadians withdrew out of range but assembled and moved forward yet again. Outnumbered nearly twenty to one, the two Canadian militia companies actually charged the ragged line of Americans in the dense underbrush. Finally thrown back again by the volume of fire, the Canadian militia broke contact. Some Americans pursued but came into view of Canadians on the left bank who opened fire across the water and checked the American advance.

Hampton, stymied on both flanks, disheartened at the obvious lack of confidence shown in his force by the Secretary of the Army, ordered a withdrawal. His division had lost about fifty men. When he received Wilkinson's order to continue on toward Montreal, Hampton refused by citing a lack of supplies and sickness among the troops. “The force is dropping off by fatigue and sickness to a most alarming extent,” wrote Hampton, “and, what is more discouraging, the officers, with a few exceptions, are sunk as low as the soldiers, and endure hardship and privation as badly.... Fatigue and suffering from the weather have deprived them of that spirit which constituted my best hopes.” Hampton resigned in disgust in March of the following year. One prong of the American offensive was defeated, by stalwart Canadians to be sure, but also by confusion and mistrust in the mind of the commander, induced not by enemy action but by the intrigue and incompetence of superiors.

Wilkinson was unaware of Hampton's fate until after his own force had been tested in battle at Crysler's Farm, and that is the subject of a future article.

More Battle of Chateauguay

- The Battle of Chateauguay October 1813.

Hampton's Official Report 1 November, 1813

De Salaberry's Official Report 26 October, 1813

Provost's General Order After the Battle

Wargaming the Battle of Chateauguay Solo Ideas

Back to Table of Contents -- War of 1812 #2

Back to War of 1812 List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Rich Barbuto.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com