General Griswold at once concluded that he could not mount a large-scale offensive against Munda until he had received reinforcements and reorganized the Occupation Force. Estimating that four battalions of "Munda moles well dug in" faced him, he planned to keep "pressure on slant-eye," and to gain more advantageous ground for an offensive, by using the 43d Division in a series of local attacks.

At the same time he would be getting ready for a full corps offensive to "crack Munda nut and allow speedy junction with Liversedge." (Rad, Griswold to Harmon, 16 Jul 43, in XIV Corps G-3 Jul, 16 Jul 43- Unless otherwise indicated this chapter is based on SOPACBACOM, History of the New Georgia Campaign, Vol. I, OCMH; the orders, action rpts, jnls and jnl files of NGOF, XIV Corps, 43d Div, 37th Div, 25th Div, NLG, and their component units; USAFISPA's Daily Int Summaries and Periodic Int Rpts; 17th Army Operations, Vol. II, Japanese Monogr No. 40 (OCMH); Southeast Area Naval Operations, Vol. Il, Japanese Monogr NO. 49 (OCMH); the published naval and air histories previously cited.)

In the rear areas, Griswold and his staff set to work to improve the system of supply and medical treatment.

The Attack on Bairoko

Meanwhile Colonel Liversedge' after taking Enogai and abandoning the trail block, was making ready to assault Bairoko. (See Map 8.) Liversedge's operations against Bairoko were not closely co-ordinated with action on the Munda front. Upon assuming command Griswold directed Liversedge to submit daily reports, but radio communication between Liversedge and Occupation Force headquarters on Rendova had been poor.

Curiously enough Liversedge's signals from his Navy TBX radio could barely be picked up at Rendova, although the radio at Segi Point was able to receive them without much difficulty. As a result Liversedge had to send many messages through Segi Point to headquarters of Task Force 31 at Guadalcanal, from there to be relayed to Rendova, a slow process at best.

In the days following the fall of Enogai, Liversedge sent patrols out to cover Dragons Peninsula. They made contact with the Japanese only once between 12 and 17 July. Little information was obtained. "Ground reconnaissance," wrote Liversedge, ". . . was by no means all it should have been." Most patrols, he felt, were not aggressive enough, had not been adequately instructed by unit commanders, and were not properly conducted. ". . . some patrols were sent out in which the individual riflemen had no idea of where they were going and what they were setting out to find."

There was always the problem of "goldbricking on the part of patrols who are inclined to keep their activity fairly close to their camp area....Patrols made "grave errors in distance and direction" and frequently were unobservant. Many returned from their missions unable to tell in what direction the streams flowed, whether there were fresh enemy tracks around a given stream, and the approximate dimensions of swamps they had passed through. (NLG War Diary and Combat Rpt, pp. 9-10.)

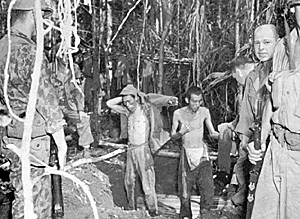

JAPANESE PRISONERS CAPTURED NEAR LAIANA BEACH are escorted to division

headquarters for interrogation.

JAPANESE PRISONERS CAPTURED NEAR LAIANA BEACH are escorted to division

headquarters for interrogation.

Prisoners might have supplied a good deal of information, but only two had been captured. Air photography, too, might have furnished Liversedge with data on strongpoints, gun emplacements, stores, and bivouac areas, but he complained that he had received practically no photos. One group of obliques received just before the landing at Rice Anchorage turned out to be pictures of marines landing at Segi Point.

Thus, except for the map captured on 7 July, Liversedge had no sound information on the installations at Bairoko. He was aware only that the Japanese were digging in and preparing to resist. The Americans could only guess at Japanese strength at Bairoko, whither the survivors of the Japanese garrison at Enogai had gone. Harmon's headquarters estimated that one Army infantry battalion plus two companies, some artillerymen, and part of the Kure 6th Special Naval Landing Force were defending Bairoko. The actual strength of the garrison is not clear. It consisted, however, of the 2d Battalion, 45th Infantry, the 8th Battery, 6th Field Artillery (both of the 6th Division), and elements of the Kure 6th Special Naval Landing Force. (Japanese sources give no strength figures for these units. SOPACBACOM, History of the New Georgia Campaign, Vol. I, Ch. V, gives approximately two thousand, a figure which may be high.)

Liversedge had few more than three thousand men to use in the attack. The move of Colonel Schultz's ld Battalion, 148th Infantry, to Triri and the 18 July landing of the 4th Marine Raider Battalion at Enogai gave him a force almost four battalions strong, although casualties and disease had reduced the three battalions that made the initial landing. M Company and the Antitank Platoon of the 3d Battalion, 145th Infantry, were holding Rice Anchorage. The 1st and 4th Raider Battalions and L Company, 145th, were at Enogai. Schultz's battalion and the remainder of the 3d Battalion, 145th, were at Triri.

Liversedge called his battalion commanders together at 1500, ig July, and issued oral orders for the Bairoko attack, which was to take place early next morning. The Raider battalions, advancing some three thousand yards southwest from Enogal along the Enogai- Bairoko trail, would make the main effort. One platoon of B Company, 1st Raider Battalion, was to create a diversion by advancing down the fifty-yard-wide sandspit forming the west shore of Leland Lagoon.

The 3d Battalion, 148th, was to make a separate enveloping movement. Advancing southwest from Triri to the trail junction southeast of Bairoko, it was to swing north against the Japanese right flank. A and C Companies, 1st Marine Raider Battalion, and elements of the 3d Battalion, 145th, formed the reserve at Enogai.

Late in the day the B Company platoon took landing craft from Enogai to the tip of the sandspit, went ashore, and moved into position for the next morning's attack. The remainder of the attacking force stayed in bivouac. From 2000, 19 July, to 0500, 20 July, Japanese aircraft bombed and strafed Enogai, which as yet had no antiaircraft guns. No one was killed, but the troops had little rest.

The two Raider battalions started out of Enogai at 0800, 20 July, and within thirty minutes all units had cleared the village and were marching down the trail toward Bairoko. The 1st Raider Battalion (less two companies) led, followed by the 4th Battalion and regimental Headquarters. At 0730 Schultz's battalion had left Triri on its enveloping march.

Fortified Position

The Northern Landing Group was attacking a fortified position. A force delivering such an attack normally makes full use of all supporting services, arms, and weapons, but Liversedge's men had little to support them. No one seems to have asked for naval gunfire. Liversedge, who had been receiving fairly heavy air support in the form of bombardments of Bairoko, is reported to have requested a heavy air strike to support his assault. His message reached the Guadalcanal headquarters of Admiral Mitscher, the Commander, Aircraft, Solomons, too late on the 19th for action next day. (Maj. John N. Rentz, USMCR, Marines in the Central Solornons (Washington, 1952), p. 111. The XIV Corps G-3 journal for 19 July contains a message from Liversedge, sent at 2235, 18 July, requesting a twelve-plane strike on 19 July, and a "large strike to stand by for July 20 A M and SBD's to stand by for immediate call remainder of day." XIV Corps headquarters replied that a "large strike stand by" for 20 July was "impracticable.")

The marines definitely expected air support. The 4th Raider Battalion noted at 0900: "Heavy air strike failed to materialize." (54th Mar Raider Bn Special Action Rpt, Bairoko Harbor, New Georgia Opn, p. 3.)

Artillery support was precluded by the fact that there was no artillery. Hindsight indicates that the six 81-mm. mortars of the 3d Battalion, 145th Infantry, might have been used in general support of the attack, but these weapons remained with their parent battalion.

The Raiders advanced without meeting an enemy until 0955 when the 1st Battalion's point sighted four Japanese. When the first shot was fired at 1015, B and D Companies, 1st Raider Battalion, deployed and moved forward. Heavy firing broke out at 1045.

By noon the battalion had penetrated the enemy outpost line of resistance and was in the outskirts of Bairoko. When D Company, on the left, was halted by machine gun fire, Liversedge began committing the 4th Raider Battalion to the left of the 1st. Then D Company started moving again. Driving slowly but steadily against machine gun fire, it advanced with its flanks in the air beyond B Company until by 1430 it had seized a ridge about three hundred yards short of the shore of Bairoko Harbour. Liversedge ordered more units forward to cover D Company's flank.

These advances were made with rifle, grenade, and bayonet against Japanese pillboxes constructed of logs and coral, housing machine guns. The jungle overhead was so heavy that the Raiders' 60-mm. mortars were not used. The platoon on the sandspit, meanwhile, was held up by a number of machine guns and was unable to reach the mainland to make contact with the main body.

So far the marines, by attacking resolutely, had made good progress in spite of the absence of proper support, but now go-mm. mortar fire from Japanese positions on the opposite (west) shore of Bairoko Harbour began bursting around the battalion command posts and on D Company's ridge. With casualties mounting, D Company was forced off the ridge.

By 1500 practically the entire force that Liversedge had led out of Enogai was committed and engaged in the fire fight, but was unable to move farther under the go-mm. mortar fire. Colonel Griffith, commanding the 1st Raider Battalion, regretted the absence of heavy mortars in the Marine battalions. Liversedge, at 1315, sent another urgent request for an air strike against the positions on the west shore of Bairoko Harbour, but, as Griswold told him, there could be no air strikes by Guadalcanal-based planes on such short notice. With all marine units in action, the attack stalled, and casualties increasing, Liversedge telephoned Schultz to ask if his battalion could make contact with the marines before dark. (All men of Headquarters Company, 4th Raider Battalion, were engaged in carrying litter cases to the rear.)

Otherwise, he warned, the attack on Bairoko would fail.

Schultz's battalion had marched out of Triri that morning in column of companies. Except for two small swamps, the trail was easy. By 1330 the battalion had traveled about 3,000 yards, passing some Japanese corpses and abandoned positions on the way, and reached the point where the Triri trail joined one of the Munda-Bairoko tracks.

Here, about 2,500 yards south of Bairoko, the battalion swung north and had moved a short distance when the advance guard ran into an enemy position on high ground. Patrols went out to try to determine the location and strength of the Japanese; by 1530 Schultz was ready to attack. M Company's 81-mm. mortars opened fire, but the rifle companies, attempting to move against machine guns, were not able to advance. One officer and one enlisted man of K Company were killed; two men were wounded. This was the situation at 1600 when Schultz received Liversedge's call.

Schultz immediately told Liversedge that he could not reach the main body before dark. A few minutes later, the 1st Marine Raider Regiment's executive officer, having been dispatched to Schultz to tell him to push harder, arrived at the battalion command post. According to the 3d Battalion's report, the executive agreed that contact could not be made before dark and he so informed Liversedge.

The group commander concluded that he had but one choice: to withdraw. He issued the order, and the marine battalions began retiring at 1700. Starting from the left of the line, they pulled back company by company. Machine gun and mortar fire still hit them, but the withdrawal was orderly. All uninjured men helped carry the wounded. The battalion retired about five hundred yards and set up a perimeter defense on the shore of Leland Lagoon. When L Company of the 145th came up from Enogai carrying water, ammunition, and blood plasma, it was committed to the perimeter. Construction of the defenses was impeded by darkness, but the task was completed and the hasty defenses were adequate to withstand some harassing Japanese that night.

Some of the walking wounded had been sent to Enogai in the late afternoon of the 20th, and at 0615 of the 21st, more were dispatched. Evacuation of litter cases began at 0830, and an hour later a group of Corrigan's natives came from Enogai to help. Carrying the stricken men in litters over the primitive trail in the heat was hard on the men and on the litter bearers. Liversedge therefore ordered that landing craft from Enogai come up Leland Lagoon and take the wounded back from a point about midway between Bairoko and Enogai.

This evacuation was carried out, and by late afternoon, the withdrawal, which was covered by Allied air attacks against Bairoko, had been completed. All the marines were at Enogai, where they were joined by Schultz's battalion, which had retired to Triri and come to Enogai by boat. The Raider battalions lost 46 men killed, 161 wounded. They reported counting 33 enemy corpses, but estimated that the total number of enemy dead was much higher.

Once again at Enogai, the Northern Landing Group resumed daily patrols over Dragons Peninsula.

More Griswold Takes Over

Back to Table of Contents -- Operation Cartwheel

Back to World War Two: US Army List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com