The Attack Against Wau

The Attack Against Wau

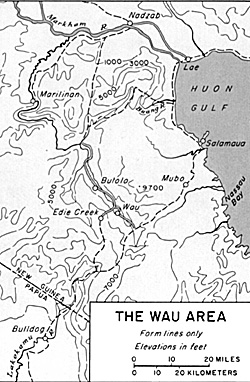

The first offensive effort under the revised strategy was directed against Wau in the Bulolo Valley goldfields southeast of New Guinea's Huon Peninsula. Wau, the site of a prewar airfield, lies 145 air miles north by west of Port Moresby, and 25 air miles southwest of Salamaua. (Map 4) Since May 1942 Wau had been held by a small body of Australians, known as the KANGA Force, who operated under control of the New Guinea Force. As the Bulolo Valley could be reached overland from other Allied bases only over mountainous, jungled, and swampy routes, the KANGA Force was supplied largely by air. It had been ordered to keep watch over Lac and Salamatia and to hold the Bulolo Valley as a base for harrying the enemy until he could be driven out of the area. (Milner, Victory in Papua, Chs. I, III; ALI, Rpt on New Guinea Opus: 23 Sep 42-22 Jan 44.)

If the Japanese had been able to establish themselves at Wan, they could have reaped great gains. They could have staged aircraft from Madang and Wewak through Wan, thus bringing Port Moresby within effective range of their fighters. (AAF Int Summary 74, 3 Feb 43, in GHQ SWPA G-3 Jnl, 2 Feb 43.)

The 18th Army entertained ambitious plans for capturing Wau and crossing the Owen Stanley Range to seize Port Moresby. It is not clear, however, whether Adachi intended to proceed from Wau over the rough trail that led from Wau to Bulldog on the Lakekamu River, or to move against Port Moresby via Kokoda. Either route would have outflanked the Allied Gona - Sanananda-Buna-Dobodura -Oro Bay positions that had been won in the arduous Papuan campaign.

When 18th Army troops moved to New Guinea in early 1941, some went to Lae and Salamaua to strengthen naval forces already there. (Interrogation of Lt Gen Hatazo Adachi, Lt Gen Rimpei Kato (former CofS, 8th Area Army), Lt Col Shoji Ota (former stf off, 8th Area Army), and Capt Sadamu Sanagi (former Senior Stf Off, Southeastern Fleet), by members of the Mil Hist Sec, Australian Army Hq, at Rabaul, no date, OCMH.)

The reinforced 102d Infantry Regiment was sent in a convoy from Rabaul to Lae during the first week in January. But the Allies, warned by the fact that the Japanese had given up their efforts to send troops to Buna, had anticipated that the Japanese might try to strengthen Lae and Salamaua and were therefore attempting to isolate that area by air action. Allied planes found the convoy, bombed it, and sank two transports. About three fourths of the 102d went ashore at Lae, but half its supplies were lost.

Once at Lae, the 102d was ordered by Adachi to seize Wau. This Allied enclave was connected to the north coast by several trails that could be traversed on foot. The Japanese commander at Lae, Maj. Gen. Torn Okabe, decided to begin his drive against Wau from Salamaua.

By 16 January he had gathered his attacking force there.

The Allies, determined to prevent the Japanese from capturing Wau and threatening Port Moresby, had meanwhile acted promptly. Headquarters, New Guinea Force, decided to reinforce Wan, and in mid-January advance elements of the 17th Australian Infantry Brigade were flown from Milne Bay to Wau. (ALF, Rpt on New Guinea Opus: 23 Sep 42-22 Jan 44; NGF 01 60, 13 Jan 43, in GHQ SWPA G-3 Jul, 14 Jan 43.)

After assembling at Salarnaua, Okabe and the 102d Infantry made their way laboriously upward to the Bulolo Valley. They struck at Wan in a dusk attack on 28 January and pushed through to the edge of the airfield. But there they were stopped. For the next three days Australian soldiers of the 17th Brigade, plus ammunition, supplies, and two 25-pounder guns, were flown in by air. In three days troop carriers of the Allied Air Forces flew in 194 planeloads, or one million pounds. So critical was the situation on the 29th that the first load of troops practically leaped from the planes firing their small arms. The Japanese pressed hard, but by 30 January acknowledged failure and began to withdraw. ( Craven and Cate, The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan, pp. 136-37; Kenney, General Kenney Reports, pp. 186-87; ALF, Rpt on New Guinea Opns: 23 Sep 42-22 Jan 44.)

Having broken the enemy's attack, the Australians kept pressing him back toward Salamaua. In April the 3d Australian Division took over direction of operations and the KANGA Force was dissolved. The Australians then halted short of Salamaua to wait until other Allied troops could be made ready for a large-scale attack against the entire Finschhafen-Lae- Salamaua complex. (USSBS, Employment of Forces, p. 17; GHQ SWPA G-3 Opus Rpt 380, 21-22 Apr 43, in GHQ SWPA G-3 Jul, 22 Apr 43.)

The Australians' gallant defense of Wan thus frustrated the last Japanese attempt to attack Port Moresby overland, and kept for the Allies an advantageous position which would help support later offensives against the Huon Peninsula.

The Battle of the Bismarck Sea

The Australian defense of Wau had a third consequence that was more farreaching than even the most ebullient Bulolo Valley veteran (if anyone was ebullient after fighting in the mud, mountains, and heat) realized at the time. It helped lead to the destruction of an entire Japanese convoy and the subsequent weakening of Lae. (Unless otherwise indicated, this brief account is based on the Japanese monographs and on definitive accounts in Craven and Cate, The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan, pp. 141-51, and Samuel Eliot Morison, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Vol. VI, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier: 22 July 1942-1 May 1944 (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1950), Ch. V.)

Okabe's attacks against Wau had so depleted his meager force that the Japanese at Rabaul, who were determined to hold Lae and Salamaua at all costs, became worried. The 20th and 41st Divisions could not be spared from Wewak and Madang. Thus Imamura, Adachi, and the naval commanders decided to send the rest of the 51st Division in convoy to Lae. They planned very carefully.

They were well aware of the havoc that airplanes could wreak on troop transports. Guadalcanal had demonstrated that point, and if final proof was needed, Adachi had had it in the destruction of part of Okabe's shipment in January. Had it been possible for the convoy to sail from Rabaul to Madang and land the troops there to march to Lae, the ships could have stayed out of effective range of Allied fighters and medium bombers; heavy bombers, thus far relatively ineffective against ships, were not greatly feared. But there was no overland or coastal route capable of getting large bodies of troops from Madang to Lae. It was therefore necessary to sail directly to Lae and thus come within range of fighters and medium bombers.

The Japanese, employing almost two hundred planes based at Rabaul, Madang. Wewak, Cape Gloucester, Gasmata, and Kavieng, hoped to beat Allied planes down out of the air and to provide direct cover to the ships.

But the Allies had deduced Japanese intentions. Ship movements around New Britain in late February, though not part of the effort to reinforce Lae, were noted by Allied reconnaissance planes. As a result air search was intensified and air striking forces were alerted. On 25 February General Kenney and his subordinates came to the conclusion that the Japanese would probably try to put more troops ashore at Lae or Madang- (See Kenney, General Kenney Reports, p. 197. See also GHQ SWPA G-2 Est of Enemy Sit 343, 28 Feb-1 Mar 43, in GHQ SWPA G-3 Jul, 1 Mar 43.)

Not only were the Allies warned; they were also ready. By the end of February airfields in Papua, with those at Dobodura near Buna carrying the biggest load, based 207 bombers and 129 fighters. The Southwest Pacific had no aircraft carriers and few if any carrier-type planes that were specifically designed for attacks against ships. But Kenney and his subordinates had redesigned the nose of the B-25 medium bomber and installed forward-firing .50-caliber machine guns so that the bomber could strafe the deck of a ship and thus neutralize all her exposed antiaircraft guns. Further, they had practiced the skip-bombing technique that proved particularly effective in sinking ships. (For details see Craven and Cate, The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan, pp. 140-41; Kenney, General Kenney Reports, pp. 21-22, 105, 144, 154-55, 162, 164. Maj. Gen. Henry H. Arnold had observed the RAF practicing skip-bombing in 1941 and introduced it to the AAF.)

Once warned, the Allied airmen prepared detailed plans for striking the convoy and executed a full-scale rehearsal off Port Moresby.

At Rabaul, 6,912 Japanese soldiers boarded eight ships. The ships weighed anchor about midnight Of 28 February 1943 and, with eight destroyers as escort, sailed out of Rabaul and westward through the Bismarck Sea at seven knots. At first bad weather--winds, mist, and rain--hid them from the air, but soon the weather began to break and Allied patrol planes sighted the convoy first on 1 March and again the next morning off Cape Gloucester.

As it was still beyond the reach of medium bombers, heavy bombers from Port Moresby attacked it in the Bismarck Sea. They sank one transport and damaged two others, a good score for heavy bombers. Survivors of the sunken ship, about 950 in number, were picked up by two of the destroyers which made a quick run to Lae to land the men after dark. The destroyers returned to the convoy on the morning Of 3 March. During the night the convoy had sailed through Vitiaz Strait and into the Solomon Sea, tracked all the while by an Australian Catalina.

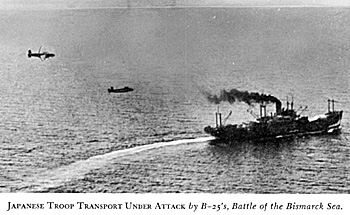

JAPANESE TROOP TRANSPORT UNDER ATTACK by B-25's, Battle of the Bismarck Sea.

JAPANESE TROOP TRANSPORT UNDER ATTACK by B-25's, Battle of the Bismarck Sea.

But now the ships entered the Huon Gulf in clear daylight, and were within range of medium bombers. The Allied planes that had organized and rehearsed for the attack assembled over Cape Ward Hunt at 0930 and set forth for the kill. The Japanese had failed to destroy Allied air power in advance, and the convoy's air cover was ineffective. Starting about 1000 and continuing until nightfall, American and Australian airmen in P- 38's, P-39's, P-40's, Beaufighters, A-20's, A-29's, Beaufort bombers, B-17's, B-24's and B-25's pounded the luckless Japanese from medium, low, and wavetop altitudes with resounding success.

All remaining transports, along with four destroyers, sank on 3 and 4 March. After night fell motor torpedo boats from Buna and Tufi swept in to finish off crippled ships and shoot up survivors in the water.

Of the 6,912 troops on board, 3,664 were lost. Including those taken by destroyer to Lae, 3,248 were rescued by the Japanese. The sinking of eight transports and four destroyers in "the most devastating air attack on ships" since Pearl Harbor was a tremendous victory, and it was won at a cost of thirteen killed, twelve wounded, and four Allied planes shot down. (Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, P-59 Allied casualty figures are from Kenney, General Kenney Reports, p. 206. Official communiques at the time, based on pilots' reports, claimed twentytwo ships and fifteen thousand men, and Kenney, in his book and in his comments on the draft manuscript of this volume, claimed six destroyers or light cruisers sunk, two destroyers or light cruisers damaged, and from eleven to fourteen merchant vessels in the convoy sunk; he also included, in his total for the Bismarck Sea, two small merchant ships that were sunk at Lae and Wide Bay. According to Kenney a second enemy convoy joined the first, which explains the disparity. However, Craven and Cate, in The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan, pp. 147-50, and Morison, in Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, after surveying all available enemy records, maintained that the convoy consisted of eight transports and an equal number of destroyers, that there was no second convoy, and that eight transports and four destroyers were sunk. 8th Area Army Operations, Japanese Monogr No. 110 (OCMH) supports them.)

The Japanese quickly changed their plans for future shipments. They decided to send no more convoys to Lae. Large slow ships would be sent only to Hansa Bay and Wewak; high-speed ships and small craft would run to Finschhafen and Tuluvu on the north coast of New Britain. Small coastal craft would take men and supplies to Lae from Finschhafen and Cape Gloucester, and some men and supplies would be sent overland from Finschhafen to Lae. In emergencies supplies that were absolutely required at Lae would be sent in by highspeed ships or submarines. The main body of ground forces eventually intended for Lae would be sent overland after completion of a road, already under construction, from Wewak through Madang to Lae.

Road Building

Construction of the road had been started in January. This most ambitious project involved building a truck highway from Madang to Bogadjim, thence over the Finisterre Range and through the Ramu and Markham River Valleys to Lae. The 20th Division was given this work.

In early February the Allies, having received reports from natives, were aware of enemy activity in the Ramu Valley. Allied intelligence deduced that the Japanese were interested in an inland route to Lae. Intelligence also minimized the danger of a serious threat, for it seemed unlikely that the road could be completed in time to be of much use. (See GHQ G-2 Daily Summary of Enemy Int and G-2 Est of Enemy Sit 317, 2-3 Feb 43, in GHQ SWPA G-3 Jul, 3 Feb 43. See also Australian Mil Forces Weekly Int Review 28, 5-12 Feb 43, in GHQ SWPA G-3 Jul, 5 Feb 43).

Allied intelligence was correct. The road-building projects were next to impossible for the Japanese to accomplish. Their maps were poor. The routes they selected, especially the inland route for the Madang-Lae road, led them through disease-ridden jungles and swamps, over towering mountains, and up and across canyons and gorges. They never had enough machinery and what they had was ineffective.

Their trucks, for example, were not sufficiently powerful to climb steep slopes. Their horses fared poorly on jungle grasses. Bridges kept washing away on the Madang-Hansa Bay road. Combat troops were unhappy as laborers. Dense forests hid the road builders from air observation, but in the open stretches of the Finisterre Range they were constantly subject to air attack. By the end of June the Madang-Lae road had been pushed only through the Finisterre Range.

Lae therefore never did receive substantial reinforcements or supplies, despite the Japanese determination to hold it and dominate Dampier and Vitiaz Straits.

More The Japanese

- Command and Strategy

Japanese Offensives: January-June 1943

The I Operation: March-April 1943

Japanese Strength and Dispositions: June 30, 1943

Back to Table of Contents -- Operation Cartwheel

Back to World War Two: US Army List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com