On the morning of May 26, 1648 near the town of Korsun, the Polish Grand-Hetman Mukola Pototcki learned of the death of his son, Stephan Pototcki, at the battle of Yellow River two weeks before. Worse, 6000 Registered Cossacks defected to Khmelnitsky and 40 Polish nobles and other leaders were taken prisoner. The Cossacks taunted and starved the nobles to gain valuable information, and later sold them to the Tatars as slaves.

Morning: Tuhai-Bey strikes first.

Later on the morning of the 26th, M. Pototcki camped across the Rosh River just 10km east of Korsun. His encampment across the Rosh gave his army some terrain advantage if attacked. Pototcki knew that a large force was moving against him from the south and he was desperately reorganizing and gathering other Polish troops within the region.

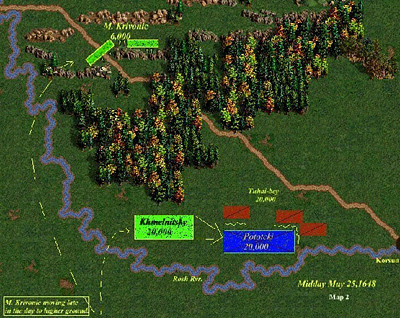

On the Cossack side, Khmelnitsky knew he had to make another strike in order to maintain his momentum. He sent forward a detachment of 6,000 Cossack cavalry (not the registered cossacks) under Maxim Krivonic 6km ahead of his main 20,000-man force. The Khan, Tuhai-Bey, broke up his 20,000-man army into three cavalry detachments and then proceeded to move Northeast of Korsun. Hidden, Tuhai-Bey hoped for surprise.

M. Pototcki reviewed his situation and decided to split his army in two giving 1200 horse and 10,000 foot to one of his Nobles and keeping the other 10,000 under his command. But before the command was issued. The Tatars began moving into position (See Map 1). At that time a small Cossack detachment of about 100 skirmishers arrived and formed up in front of the Polish army. [3]

Midday: With the tartars on one side and the cossacks on the other, the Poles resist as best they can, but prepare to fall back into the woods.

For the Polish nobleman to tolerate such insults was a fate worse then death. The Cossacks would begin laughing at them, egging them on to come out and conduct personal duels or jousts. Some Cossacks would dance in front of the Polish army and roll around on the ground laughing at the Poles. Some would play flutes or parade around taunting the soldiers. The Cossacks would display their derriere and whistle at the Polish Cavaliers. Some Poles found this so insulting that few did break ranks to go forth and honor the duel set forth only to be killed quickly by the Cossacks swordsmanship. Not only did this become a morale booster for the Cossacks but a demoralizing scene for the Polish troops.

The insults and thirst for revenge from the loss at Yellow River finally caused the Polish Nobles to move their troops to attack the skirmishing Cossacks. A volley of musket fire failed to scatter the Cossack rabble-rousers. The forced Polish response led to the morning attack of three detachments of the Tatar cavalry from the west of Korsun. As the Tatars closed, the Cossack skirmishers withdrew allowing the Tatars to fire their bows. The first volley proved deadly, striking down hundreds of Polish foot and cavalry. The Polish nobles would then fill the ranks and begin firing into the oncoming Tatar cavalry. But the gunfire did not stop the Tatars. The Tatars engaged the Polish foot and began fighting man to man. Some Poles were purposely decapitated and Tatar soldiers would place the heads on their lances to display their prize. Also, during the frenzy of the fight some would toss the heads back into the Polish lines to demoralize the troops.

Khmelnitsky Arrives

By midday there was no clear victor until Khmelnitsky arrived on the battlefield. He moved his mobile camp east of the main Polish army, across the Rosh River, and began engaging the Polish right flank. The Poles were now facing a force twice their size and being attacked from front and flank. It was far too much for the Polish army to endure.

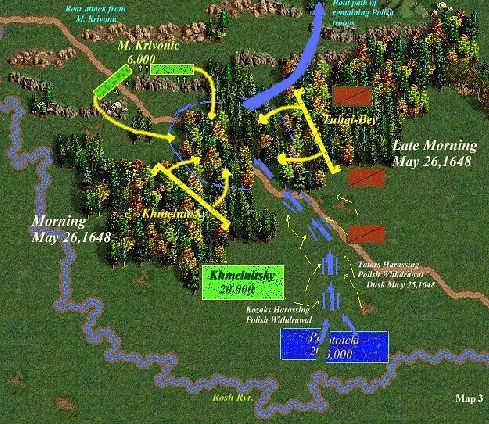

Pototcki ordered his wagons to be moved to force a breakout. They maneuvered the wagons such to create a corridor for the soldiers to move north into the cover of woods. By late afternoon the entire Polish army successfully moved into the wooded area. It was a short triumph. Tatar and Cossack soldiers harassed them continually. Ultimately, both sides, now exhausted after a day of fighting, settled in the wooded area northeast of Korsun. Fighting slowed with the exception of some minor skirmishes in the evening hours.

Unknown to Pototski, one of Khmelnitsky’s general, Maxim Krivonic (means "Crooked Nose"), took 6000 Zaporozhians with their artillery at midday and made his way north, guessing correctly that if the Polish army withdrew, he would cut off their escape route. By early evening, Krivonic was able to place guns on an embankment and through the night harass the Polish position by lobbing shells into the woods. The cannon fire kept the Poles on edge and further demoralized the remaining army.

On the morning of May 27, 1648 the Polish army tried to attack the embankment to make way for another breakout with a plan to take the high ground. Yet the Cossacks and Tatars resumed the assault. Khmelnitsky began his attack in line formation and harassed the right flank while the Tatars harassed the left flank. Krivonic supported both assaults and rushed his Cossacks in a pincer maneuver to deliver the final blow. It did not take long to smash through the Polish wagons and lines, causing the Poles to rout, essentially eliminating the Polish army as a fighting force. The Cossacks and Tatars captured weapons, food, and clothing within the camp. Some Polish soldiers were killed when they offered to surrender.

Morning. The final pocket: Hit on three sides, the Polish army crumbled.

Mukola Pototcki and many Polish noblemen were killed that day. Those that survived as prisoners were put into chains. The Polish Corp was decimated after the second day. Of the 1200 horse and 10,000 foot that started the battle, some 8,500 were kiled and the rest routed. The victory for the Cossacks and Tatars sent a chilling message to the Polish crown, forecasting a change in the military balance.

Bohdan Khmelnitsky became a hero to the Cossacks, and the victory lured many peasants to join the ranks of the Cossacks. The Zaporozhian and Tatar armies, strong and well supplied, soon became unstoppable. The Ukrainian steppes were literally on fire as the armies moved against Poland.

The revolution had received such a momentum that it was difficult to stem it. It would take several more years of fighting and negotiations before Poland would finally restore ancient privileges, bestow Cossack independence, and recognize Khmelnitsky as hetman.

The battle cemented Khmelnitsky as one of the fathers of the Ukrainian nation. His campaigns freed Ukraine from Polish domination, and, in the process, fulfilled his quest for personal revenge. Although stability in Ukraine would take many more decades, the birth of a nation had begun.

[1] Website: http://artiom.home.mindspring.com/cossacks/sech.htm)

Battle at Korsun: May 26-27, 1648 The Zaporozhian Cossacks

Khmelnitsky’s main force was still 12 kilometers away. The Polish army began forming a defensive camp surrounded by wagons. In the middle of all the maneuvering several Zaporozhians would break rank and began taunting the Polish nobles. They would yell out insults to them, such as: “You cavaliers ride on asses as your mighty steeds!” or called them “cowards hiding behind your mother’s apron”.

Khmelnitsky’s main force was still 12 kilometers away. The Polish army began forming a defensive camp surrounded by wagons. In the middle of all the maneuvering several Zaporozhians would break rank and began taunting the Polish nobles. They would yell out insults to them, such as: “You cavaliers ride on asses as your mighty steeds!” or called them “cowards hiding behind your mother’s apron”.

May 27, 1648

May 27, 1648

Footnotes

[2] Website: www.cossack.com

[3] How Cossacks Fought by I. Cteshenko and C. Mittsik.

Back to War Lore: The List

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by Michael Meusz.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com