Ancient India, shut off from the outside world by oceans and mountain walls, and for

centuries maintaining a stylised mode of warfare, would have been a fertile breeding ground for the wargame. similar situation prevailed in 18th century Europe, the Age of Reason, when a mathematical formula for the conduct of war was sought and the wargame was revived.

Ancient India, shut off from the outside world by oceans and mountain walls, and for

centuries maintaining a stylised mode of warfare, would have been a fertile breeding ground for the wargame. similar situation prevailed in 18th century Europe, the Age of Reason, when a mathematical formula for the conduct of war was sought and the wargame was revived.

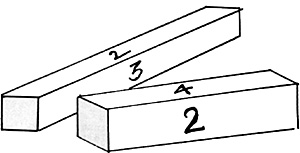

Chaturanga's 'Long Dice' were four sided and renumbered 2,3,4,5, so that opposing faces tota1ed seven as in the cubic variety. They were rolled along the palms of the hands and then onto the table. It is not certain whether one or two dice were used or whether dice were employed throughout the game.

It is known that as early as 500 BC field manoeuvres were carried out involving practically all the armed forces on the Indian subcontinent. The research into various battle arrays lasted 18 days. Wars, being highly chivalrous affairs often stimulated from obscure diplomatic reasons, carried in their wake an abundance of textbooks on military lore. Diplomatic works listed every conceivable motive for war; greed, folly, ambition, love of a woman, etc., and Kings were expected to know how to "play off" enemies against allies by adhering to intricate codes of conduct. "Duplicity" for instance, was an equal of "Peace" in a Kings six-fold policy. Most of the textbooks offered so many conditions determining courses of action together with their opposites and balancing variables that they read like present-day wargame campaign rulebooks.

It is for this sphere of military education, not readily accessible to the general public of that era, that Chaturanga stemmed, and there seems little reason to disagree with the words of the Arab historian Al Masudi who in 950 AD wrote, that in India, "the game of chess became a school of government and defence; it was consulted in time of war, when military tactics were about to be employed, to study the more or less rapid movement of troops."

This cosy world of idealised warfare was brought back to earth with a jolt when Alexander invaded India in the 3rd century BC. If the wargame Chaturanga did exist then in a professional status, it was from then on doomed to a Dark Age until its resurrection by the Prussians 2000 years later.

The oracle workers of the ancient Indian army had no part to play in the subsequent growth and transformation of Chaturanga in the centuries following the birth of Christ. In the meantime the game had been adopted by the non-military as a compulsive gambling game in which the stakes ran high. Estates, principalities, petty kingdoms, wives and children were all fair bets; in fact it was not uncommon for players to wager their own limbs. For games of this sort a cauterizing vessel was kept nearby to staunch the flow of blood. As a last resort, the loser, providing he still retained at least one useful appendage, was often inclined to subdue his opponent by wielding the heavy board as a club-like weapon.

Not surprisingly, despite shrill claims that the invention of Chaturanga was a well meaning Buddhist attempt to supplant real warfare by a game, the Hindu authorities were forced to adopt a hard line; all gambling was forbidden in their culture. Though hard pressed, the Chaturanga players found they could evade the new laws merely by discarding the dice. In time the allied pieces were regrouped at opposite ends of the board and present day chess was born.

The practice of allotting stakes to the capture of Chaturanga pieces was just one of the many principles lifted from the ancient textbooks of war. The State awarded special prizes for feats of valour in battle, e.g. to kill a hostile king deserved an award of several gold pieces. A typical list of graded awards attached to the destruction of parts of the enemy force ran as follows: coin, kind, both, share of the plunder, land, and 'special' rewards.

Hindu policy maintained that every king should consider his nearest neighbour as an enemy and that neighbours enemy as an ally. This is paralleled in the doubtful alliance between each pair of partners in Chaturanga. Not only is each player dependant on the whim of the dice; partners are separated from each other by the moves of their adversaries. Players are allowed to seize the "throne" (kings square) of allies, and even to capture that ally's rajah. From then on the force i that ally is annexed and under the control of the capturing player. A player that suffers this reversal of fortune is not necessarily put out of the game, as ransoms and exchanges of prisoner and kin, may be negotiated.

Chess has relinquished these diplomatic aspects apart from the factor of pawn promotion. Checkmate also was a later innovation. The object of Chaturanga is for one pair of partners to capture both hostile rajahs on which the pool or "treasure" is shared by the winning allies; or for one player to capture all three rajahs after which he is said to have built an empire, and is able to claim the pool for himself.

Treaties between partners may be negotiated, though there is no provision for them in the surviving rules. However, one ancient military tract describes four methods of treaty bargaining which could easily be adapted for a modern version of Chaturanga. They are: Peace with Honour, Territory, Treasure and part of an army.

The inclusion of rules for morale would have been unthinkable in days of yore. The modern professional attitude does not differ. In "Venture Simulation" Alfred H. Hausrath writes that morale "can neither be predicted or measured." Neither, he adds, can training, leadership, fatigue, fear, courage or stress. These factors are therefore omitted from operational research methods.

"Pop" wargamers, humanitarians one and all, would consider morale indispensable in a wargame. To up-date Chaturanga in this respect, and also to make it possible for board wargamers to deploy a greater range of figures in place of the simple chess pieces, the following list of regimental qualities quoted in one of the Hindu military textbooks may prove useful. In descending order they are:

- Hereditary armies; Mercenary armies; Guild armies; Allies or prisoners; Wild tribes.

Another ancient military writer, Sukra, further classifies these as follows:

- Good

- Long standing armies

Trained armies

Officered by state

State equipped

Own troops

Hereditary troops

Bad

- New recruits

Untrained armies

Not officered by the state

Supplying themselves

Allied troops

Mercenary troops

A more complex table of combat values can thus be worked out using the above as a model, which should satisfy boardgamers reared on simulation techniques.

Another possibility for 'improving' Chaturanga is the utilisation of the earlier race game Ashtapada as a preliminary sumbolic campaign. The four pieces used by each party can be envoys, whose duty is to build up affection or disaffection among the other states. Successful home rules can be rewarded by a choice of size and type of armies for the ensuing battle. There are plenty of ideas to be found among the list of books given in the first article of this series that will help to lay a veneer of sophistication to the rough and ready rules of Chaturanga as they have been handed down to us. With a little application Chaturanga may hopefully oust "Middle Earth" as the latest wargaming rage.

From experience I have found the "missing link' Chaturanga, to hold a fatal fascination for the wargamer who possesses the gambling instinct, and there have been moments when I have felt that the days of the cauterizing vessel were not so distant. Therefore as a gentle warning I would remind readers that the laws of chivalry in ancient Indian warfare were extremely generous, but as an added safeguard Monopoly money can provide a fair substitute for the real thing!

| Table of moves and values | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chaturanga Piece | Corresponding Chess Piece | Stake Value | Dice roll to move | Move | Piece it is Permitted to capture |

| Rajan | King | 5 | 5 | As King in Chess | Any |

| Elephant | Rook | 4 | 4 | As rook | Any |

| Horseman | Knight | 3 | 3 | As knight | Any |

| Chariot | Bishop | 2 | 2 | 2 squares diagonally 'hopping' as necessary | Chariots or Pawns |

| Infantry | Pawn | 1 | 5 | As Pawn | Chariots or pawns only |

Back to Table of Contents -- Wargamer's Newsletter # 168

To Wargamer's Newsletter List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1976 by Donald Featherstone.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com