THE MISSING LINK

THE MISSING LINK

It may never make front page news, but as a topic for mild debate the ancient history of wargaming still remains an open arena for armchair pschychologists and barrack-room lawyers alike. Both parties would agree that 'War' and 'Play' are among Man's earliest known preoccupations. What has not been satisfactorily explained is why, when and how these apparently irreconcilable concepts united to become the "wargame".

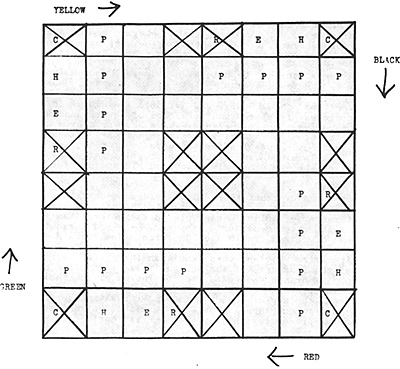

R = Rajah, E = Elephant, H = Horseman, C = Chariot, p = pawn.

The Chaturanga board and coloured pieces are adapted from the race game Ashtapada, which developed out of pachisi, an ancestor of Ludo. There is no chequering, and the cross-cut squares which in the race game signified immunity from capture are retained. Red and Yellow; Black and green are allies.

One thing is certain, wargaming in one form or another has been around a long while. At the present state of its evolution the word encompasses anything from draughts to systems analysis; 'Cowboys and Indians' to the planned manoeuvres of a real life fleet in the Med.

With a definition as overloaded as that, the field for argument is wide indeed. To further complicate matters its disciples have formed two factions; the Professionals who play war in order to learn how to kill more efficiently, and Amateurs who play for fun. Who came first; the 'Warmonger' or the 'Popgamer'? Although the modern amateur follows trends set by the professionals it was not always that way. And going still further back in time these roles may have been reversed yet again. Like a family tree, wargaming's 'male' lineage -- meaning the professional variety -- can be traced back for several generations before getting lost in a maze of inter-marriages.

Ponderous, bull-necked, grandfather Kreigsspeil for instance, born circa 1800 out of War Chess, which was itself sired by the King's Game chess variant of 1644, makes a respectable enough pedigree for a start. But we are now talking about Chess; a 'fun' game and therefore a different branch of the family entirely.

But is it? Abstract board games may seem remote from the sophisticated Napoleonic wargame played upon a large scenic table, -but in "History of Chess", H.J.R.Murray gives their collective definition as: "games played on an arranged surface with pieces or men, in which the powers of move and capture are defined by the rules". Even "Little Wars" played on the lawn of a country garden fits this broad description. However the history of boardgames is a sticky, scholarly field on which to attempt to justify the purity of wargaming's genealogy. Knowledge of the really ancient games is scarce and has been distorted by time.

When the inveterate games players of Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt went to their tombs taking with them their game boards and pieces to while away the dead and dusty centuries, none of them felt it necessary to include the rule books so that later inviolaters could take up where they left off. And of those games that did survive, Chess is not the only one that can lay a hereditary claim to being the Father of Wargaming.

Another contestant is the Japanese game "Go", which developed out of the Chinese Wei Chi, or Game of Encirclement. Chinese historians assure us that Wei Chi was around at least as early as 500 BC, the year that the military author Sun Tzu wrote "The Art of War"; a book that with just a little stretching of the imagination could be viewed as a primer of Wei Chi also. "The art of using troops is this", writes Sun Tzu, "when ten to the enemies one, surround him". And: "To capture the enemy's army is better than to destroy it". In the Russo-Japanese war of 1905, Japanese strategy seemed to Western observers suspiciously akin to the principles of "Go" even though German Kreigsspiel had by then been adopted in Japan.

Chess

Chess is clearly the more correct antecedent of modern professional wargaming than the inscrutable "Go", but as most really ancient boardgames show similarities of concept it would be tempting to narrow the field by implying a common ancestry for them all. Unfortunately not all early boardgames were games of war, and in any case games historians are unsympathetic towards applying the Darwin theory in this way. Yet in spite of their scepticism and the fact that the single parent game has never-been established, 'missing links' have been sought and were sometimes found.

One such example was uncovered by 18th century scholars who were puzzled by the frequent use of the term "Chaturganga" in the epic poetry of ancient India. Literally the word mean "Four Limbs" and clearly referred to the four branches of Hindu army organisation which then were Chariots, Elephants, Horsemen and Infantry. Yet in another sense the term could be used to describe the pieces used in a boardgame now believed to be the antecedent to chess.

"The self consistency of the nomenclature", writes Murray, "and the exactness with which it reproduces the composition of the Indian army afford the strongest grounds for regarding Chaturanga as a conscious and deliberate attempt to represent Indian warfare in a game."

Was it a spontaneous creation? Or did Chaturanga's roots spring from some hidden mystical source? The Indian military theorist, V.R.R.Dikshita, has indicated that there may be a more profound significance to Chaturanga; a significance that European historians with their feet planted firmly on the ground may have overlooked. In "War in Ancient India" he suggests that the elaborate and sometimes inexplicably formal rules of early Indian warfare may have actually been inspired by the boardgame Chaturanga, and not, as might be expected, vice-versa. He cites as one instance the over emphasised tactical valise of the elephant in Indian warfare which seems directly related to its powerful performance on the Chaturanga board. In reality the elephant was a most unpredictable animal which in the heat of battle was equally likely to overrun its own forces as the enemies, in a panic stricken stampede.

The assumption that a wargame should drastically influence military thinking would not surprise anyone familiar with operational research techniques: modern man's military oracle. Yet the computer is"the only radical change in the Chaturanga methods of simulating warfare in an inert and miniaturised form. "Pop" wargaming has inherited this legacy through Kreigsspeils close relationship to chess. The basis of the time/space scale for instance, was laid down in the Chaturanga rules.

The cavalry move, (same as the chess knight), was described in Indian literature as "Forked Lightning", relating to both the swift striking, power of horsemen and the magical one-up-one-across one-up direction of its move. In contrast the infantry "pawns" move slower, are disciplined enough not to turn back in an advance, and must attack their enemy (except Rajahs and the powerful elephants) by slashing like swordsmen to the right and left diagonally. In addition the 4:1 proportion of pawns to other pieces approximates the huge numbers of infantry that were employed on the field of battle. The army of Pauras for instance, that unsuccessfully opposed Alexander's invasion of NorthWest India in 326 BC used 30,000 infantry, 4,000 cavalry, 200 elephants and 300 chariots.

In ancient Indian warfare the chariots and elephants would bear the brunt of an attack by attempting to break the enemies files and then reform behind their own ranks.

In Chaturanga the elephant and chariot pieces are allowed to move backwards or forwards. The chariots diagonal move, which is designed to echo the oblique charge of wheeled transport is given added versatility by being permitted to hop over intervening pieces.The elephant, unable to 'hop', either crashes through the opponents force or shudders to a halt before its own men:;

Although chess retains many features of Chaturanga, there are two important differences; the earlier game was played four handed; and moves were controlled by dice. Dice caused a variety of problems as will be seen later, and the surviving rules are somewhat ambiguous owing to the Hindu literary practice of veiling fact with myth, but board wargamers with exotic tastes need not gnaw their joss sticks in frustration, for with a little ingenuity coupled with some basic knowledge of the tactics and diplomacy of ancient Indian warfare, (see bibliography), Chaturanga can be adapted for experimentation.

Using a normal chess board (or even a scenic version) a de luxe set of Chaturanga pieces; elephants chariots, etc., can be chosen from Minifigs exhaustive range. Played as a relaxing change from all those complex modern simulation boardgames, Chaturanga's antiquity alone lends it a special charm. The development of Chaturanga, the 'missing link', will be discussed in a further article.

Games for Children

The belief that all games are the prerogative of children is a fairly recent one. Before the 17th century there was no such thing as a specific childrens game; no generation gap-in games existed. (Which m4 ht make a whole lot of adult wargamers feel less guilty about their indulgence in "playing soldiers"). Even today the dividing line that separates play from reality is not as distinct as it may seem; after all professional football is taken seriously enough! Any of man's activities becomes a game or sport in a different context: hunting, for example; or athletics, which started out in ancient times as a routine army exercise. One of the natural processes of growing up is to mimic ones elders, and this class of game which usually involves 'toys' is also the basis for teaching adult skills such as archery, flight simulation, etc.

All of these activities, whether in the category of children's games, adult sport or technical instruction, intermix to form new hybrids and thus their origins become lost. The boardgame is someg thing else again. Its origins lie in long forgotten magico-religious rites. The Chance Element is the integral factor and is a survival of a primitive religious practice whereby the Gods were invoked to foretell the consequences of future actions.

At an early point in culture this was achieved by Arrow Divination. Ceremonially the arrow was as personal to its owner as modern man's signature, and the coded patterns formed by a bundle of arrows shaken from a quiver were expected to supply an irrefutable answer to even the most profound problem. According to the 19th century American games historian, Stewart Culin, the Divination Arrow may have been the forerunner to all accepted chance methods such as dice, dominoes, playing cards, etc. It is possible that playing boards and pieces originally served the same purpose as a cribbage board, i.e. a record of the complex chance effects produced by the dice. Equally, the squared board may have been viewed as a primitive plan or map.

Early civilizations flourished within areas confined by natural boundaries, and in these small worlds everything was classified according to the four cardinal points of the compass. Korean battle flags, for instance, bore the colours of the world quarters, and the ancient Chinese arranged their war camps to-their own system of "Four Directions": NE, SE, SW, and NW. (This diagonal influence survives in the board game "Go", where the pieces are placed on the angles of squares and not in the spaces). Several fanciful theories -- and theories they will remain -- have been put forward to account! for the transformation of the military oracle into the game of war, e.g. a military commander, marking out a plan of his territory in a patch of sand, using pebbles for the opposing forces, and with the aid of the sacred dice summoning the Gods to help him decide his most appropriate strategy, may have excited the interest of civilian eye witnesses who would have later copied his actions for their own amusement.

Most writers on early boardgames however, assert that there is no evidence that games were ever used in the professional sense to work out military strategies. Certainly there is no evidence that the great commanders of history such as Alexander or Julius Caesar played them other than for amusement. Maybe the commanders of the more warlike races considered manpower cheap and wargaming a cissy occupation, but it cannot be denied that the civilized creators of Chaturanga possessed a great deal of inside knowledge of the strategy and behaviour of ancient Indian armies. This fact alone would indicate some personal involvement' on their part. Who they were, and when they made their discovery will never be known. Cavalry became one of the four arms of the ancient Indian army from 600 BC (the post Vedic period), and chariots ceased to be a branch soon after the beginning of the Christian era. .In the earlier period chariots were the dominant arm; elephants became most important from 400 BC. If the prototype game of Chaturanga was one of the devices used by Indian army astrologers who were always consulted before an expedition was undertaken, then it could be surmised that Chaturanga originated somewhere within the four centuries preceeding the birth of Christ; earlier if Mr. Dikshita's theory is to be believed.

However, many chess writers -- Arthur Koestler among them -- who believed that the game was a purely "amateur" creation, place its date of origin much later; around the 5th century AD. The truth is elusive, as ancient Indian epic poetry still mystifies both games historian and military theorist alike. Govind Tryambak Date in "The Art of War in Ancient India", states that many secrets may still lie waiting to be discovered in the study of the lore of warfare charms and spells which modern military writers have generally overlooked.

Bibliography

For the rules of Chaturanga -- A History of Chess A.J.R.Murray, Oxford Clarendon Press, 1962 and Board and Tables Games, Vol. I R.C.Bell, London University Press. 1860.

For early Indian warfare: War in Ancient India V.R.R.Dikshita, 1948; The Art of War in Ancient India P.C.Chakravarti, University of Dacca 1941; The Art of War in Ancient India Govind Tryambak Date, Oxford 1929 and Military History of India Jadaneth Sarkar 1960. Also -- Puranic Mythology E.W.Hopkins; Original Sanskrit Texts J.Muir and The Art of War Zun Tzu (Trans. S.B. Griffith) 1963.

Back to Table of Contents -- Wargamer's Newsletter # 167

To Wargamer's Newsletter List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1976 by Donald Featherstone.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com