Colonial Williamsburg measures one mile long by one-half mile wide with about 130 buildings. It's a mix of 88 restored buildings and about 40 built brand new upon 18th Century foundations. I didn't count them.

Colonial Williamsburg measures one mile long by one-half mile wide with about 130 buildings. It's a mix of 88 restored buildings and about 40 built brand new upon 18th Century foundations. I didn't count them.

A typical section of Colonial Williamsburg.

In any case, they all look appropriately colonial American, and most included a garbed docent outside clicking up a storm on a handheld counter to record how many folks visit a particular structure. I don't know what happens if they fall behind a quota--maybe they're flogged at the public square. I bet Colonial Williamsburg doesnt get too many volunteers for the flogging, which must, by definition, be real and so draw blood. Or maybe they just get placed in the stocks.

Anyway, just about all the buildings also include a garbed docent on the inside ready to offer information and demonstrations about 18th Century crafts and life. Colonial Williamsburg covers 173 acres in total.

We admit that after the Governor's Palace excursion, we tried to avoid guided tours. We couldn't do so entirely, but it made the visit more enjoyable.

Exiting the Governor's Palace, a wide grassy avenue leads you into the main part of the town. Employees in period costume roam the streets, adding a little Disney to your stroll along Duke of Gloucester Street. Yeah, it's a little goofy, but that's the tourism trade. That said, these docents are extremely well-trained, providing enough commentary and information to keep your interest for the few minutes you spend in each shop or building. It's history for those with a short attention span.

At the other end of this long avenue sits the Bruton Parish Church, built in 1715 with the steeple added in 1769. Before we reached that, we turned left onto the main drag, Duke of Gloucester Street.

At the other end of this long avenue sits the Bruton Parish Church, built in 1715 with the steeple added in 1769. Before we reached that, we turned left onto the main drag, Duke of Gloucester Street.

Bruton Parish Church

At the far end sits the Capitol building. As this was a tour, we avoided it, but the building is a reconstruction of the 1705 building that burned to the ground in 1747. I don't know why they didn't rebuild it in the 1748 fashion, but there you have it.

In between are numerous buildings housing artisans and shops. We stopped in the post office to buy some postcard stamps and mailed a few postcards.

Printing Office and Bindery

Descending the narrow and steep steps behind the post office, we found the closed door to the Print shop with a "Visitors Welcome" sign. As we had seen a couple exit, we walked in. A young man stood behind a wooden printing press and discussed the wonders of type and printing. It's easy to select the "print" option off a menu these days and hear the hum of a laser printer spit out a sheet of text, but back in the colonial days (and indeed up until the Linotype machines received widespread use in the late 1800s), it was hand-set type that made newspapers.

As a journalism major at Syracuse University, one of the freshman-level classes was a history of newspapers, and that included, and I kid you not, setting metal type by hand. You were graded not on speed, but on accuracy and appearance--justification of text on the left and right margins is an art form. Believe you me, setting a few column inches of text by hand could quickly drive you crazy.

If you want to know why letters are referred to as "upper case" and "lower case," it's because the type was separated into capital letters and small letters in a case filled with compartments. Each compartment held a multitude of type of one specific letter. The speed of setting type meant that letters used most often were closer to the rack that held the column inches. Since the smaller letters were in the half of the case closest to your body--we call small letters "lower case" as they were in the bottom case. Capital letters, used less often, were in the case farthest away--the upper case.

If you want to know why letters are referred to as "upper case" and "lower case," it's because the type was separated into capital letters and small letters in a case filled with compartments. Each compartment held a multitude of type of one specific letter. The speed of setting type meant that letters used most often were closer to the rack that held the column inches. Since the smaller letters were in the half of the case closest to your body--we call small letters "lower case" as they were in the bottom case. Capital letters, used less often, were in the case farthest away--the upper case.

Another scene on Duke of Gloucester Street.

You have to remember the printing process. You set type in newspaper columns, ink the tops of the type where the letters have been formed into sentences and paragraphs, place a piece of paper on a wooden plate and then haul on the lever that drops the wooden plate and paper atop the type and "presses" the inked letters onto the paper. This is not exactly the fastest process, but in its day, two men working in tandem could turn out a fair number of newspapers and other flyers.

Think about it. If the paper presses on the type, the letters must be formed backwards (mirror image) in order for the letters to be read as normal on the page. That means the typesetter was working backwards with reversed letters.

Think about it. If the paper presses on the type, the letters must be formed backwards (mirror image) in order for the letters to be read as normal on the page. That means the typesetter was working backwards with reversed letters.

As you exit the Palace, a scene along the Palace Green.

Now, I was taught that the expression "mind your P's and Q's" also came from printing. The type letter "p" and letter "q" were next to each other in the case. If you were working in reverse and reached for a "p" or "q", you might retrieve the wrong one. Worse, you might not notice it. Thus, new appretices were told to pay attention to those letters.

However, when I dredged that tidbit from my memory, the printer said that there was another possibility. It comes from the French, from Pied (foot) and Q something (wig). If you remember the pre-minuet posturing as explained in the Governor's Palace, the foot must be extended and the head held high to prevent the wig from falling off. The expression to mind your P and Q meant to pay attention to your posture. Go figure. Leave it to an editor to question a perceived notion, although this particular docent did not opine which was right.

By the way, the paper used was cotten-based, not wood pulp.

Wigmaker

Wigmaker

This was somewhat interesting. I learned more about powdering wigs, wigmaking, and wig selection than I really wanted to know. Thumbs up to the docent making a wig for staying in character and imparting information. Next to the celloist, this was my favorite docent, if one is allowed to have a favorite historical interpreter. The Wetherburn tavern guide was a close third, but he wasn't in costume.

The wigmaker in action.

Wetherburn Tavern

As we wandered down Gloucester Street, we hit the right time for a tour (sigh) of Wetherburn Tavern, built in 1743 and yielding close to 200,000 artifacts as well as a 1760 room-by-room inventory of everything owned by Wetherburn. Mr. Wetherburn worked as a young man in a different tavern, until he found a chance to open his own, and also married a widow who ran another tavern down the street.

Fortunately, the group was small enough that we could shuffle through the place quickly. Taverns served as modern hotels, with rooms (public and private), food, and drink. We were led into a semi-formal room that could be rented out for small social occasions. Period furniture and images grace the room, which led to the private resident of Mr. Wetherburn in the back.

Here, his whole family stayed in a very small space, perhaps 10' x 20' or so, later expanded. From here, back through the rentable room, we reached the main bar. Tables and chairs, some gaming items, and other pub items greeted us. To the right was a much larger room, with ample space to seat 14 at two large round tables and a great big marble fireplace. A quick look and it was up the stair to the rooms.

Taverns were regulated back then, and all of them had to have a public space, a private space, and set prices for food, drink, and accomodations. We saw the public space first. It had a couple double beds, some chairs, and space for the colonial equivalent of sleeping bags.

Taverns were regulated back then, and all of them had to have a public space, a private space, and set prices for food, drink, and accomodations. We saw the public space first. It had a couple double beds, some chairs, and space for the colonial equivalent of sleeping bags.

Rest assured, the baker and candlestick maker were also in town.

Now, when it said public, it meant public. And just because you shared a room didn't mean you got your own bed. Indeed, as many as three people shared a bed. Considering the personal hygiene back then, it's no wonder many took to the floor.

Incidently, the phrase "sleep tight and don't let the bed bugs bite" comes from this era. The beds' springs were ropes cross hatched underneath the mattress. The sag of the mattress could be adjusted by pulling the ropes taut, a.k.a. tight. If all the sleepers didn't want to end up in a lump in the middle of a sagging bed, they made sure the ropes were "tight." The bed bugs you can figure out on your own.

Private rooms cost more and included such amenities as your own bed (though you would share a room with a stranger unless you paid for the entire room, as some wealthier legislators did).

Finally, we went down the stairs and out to the backyard and the separate structures that housed the kitchen, laundry, and slave quarters. Who's the most valuable slave? The head cook, because a tavern's reputation was not only the drink and overnight accomodations, but the food, too.

Silversmith

Silversmith

A shop selling a variety of silver goods was in the front, but in the back, the silversmith plied his trade.

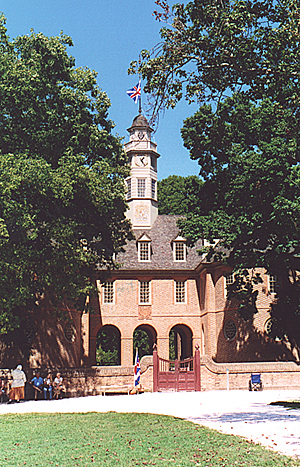

The front of the capitol building.

Millener

A lady sewed in the front and kept up a constant description of items and the history of the lady who owned the establishment. Period garb lined the walls, although most were in boxes, which, so the docent said, was how merchants stored such goods. They would bring out the various cloth and so on if you asked, or if they believed they could figure out what you wanted.

Gunsmith

Just beyond the Capitol was the gunsmith shop. This baffled me, as I expected to hear about the making of guns. Instead, it was about the assembly of guns. According to the docent, the gunsmith assembled them from stock parts. Only rarely did he create a gun from scratch for a client. He made repairs as well, but from the description, it was more shopping than crafting, although he showed a rifling gizmo.

The main problem is the severe disconnect I had with the docent, who kept switching his information between 1774 and modern day practices. Everytime I switched with him, he'd switch back. I gave up and left.

Armistead Site

Back past the capitol, we passed the Armistead Site, an excavation in progress, although on that particular day, no one was working. They had excavated the foundations and protected them with a roofed enclosure. A small informational sign told of what the building used to be--see the jumbo phot for details.

Oddly enough, the sign said it was Mr. Charlton's coffeehouse, while the map said Armistead Site. Go figure.

Jumbo Armistead Site (very slow: 292K)

Behind that was the Secretary's Office, although it seemed more a mini-stage with fancy plank benches. There is a little shop inside that sold a variety of items. As the day was hot, we bought a bottle of water ($1.50).

Behind that was the Secretary's Office, although it seemed more a mini-stage with fancy plank benches. There is a little shop inside that sold a variety of items. As the day was hot, we bought a bottle of water ($1.50).

Secretary's Office

Lunch

Behind the Raleigh Tavern is the Raleigh Tavern Bakery. The actual tavern was closed for renovation while we visited, but we made our way down the side walkway to the rear of the tavern and entered the bakery.

We ordered ham biscuit ($2), which is a slab of smoked ham in a biscuit, and some Colonial Williamsburg root beer ($1.75). Besides being enough of a snack to hold us until dinner, the root beer was particularly good. We originally wanted lemonade, but they were out. The root beer was something specially bottled for them.

More Colonial Williamsburg

- Introduction

Governor's Palace

Into Town: Shops

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Museum

Arms Magazine Area

Where to Stay, Eat, and Play

Back to List of Historic Sites

Back to Travel Master List

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 2003 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles covering military history and related topics are available at http://www.magweb.com