THE CAMPAIGN FOR PHILADELPHIA

Southeastern Pennsylvania was an area vital to the American cause in 1777. In addition to food, this region supplied large amounts of cloth for uniforms, leather for shoes and accoutrements, iron, finished muskets and rifles, salt, soap, livestock for food and transportation, wagons, and even the paper for all state and Continental currency. Three powder mills produced munitions for Washington's army. If the British could conquer this region they would not only cut the rebelling colonies in two and capture their capital, Philadelphia, but also would deprive the Continentals of crucial resources. British army commander General William Howe thought all this was possible.

In the spring of 1777, Howe launched an overland attack south from his base in New York City. Blocked by Washington's army in New Jersey, the British embarked 15,000 men on July 23rd in 264 ships and sailed south. Howe's plan of striking up the Delaware River was thwarted by the rapid movement of the Continentals from the Hudson highlands to below Philadelphia, where the Americans had prepared fortifications earlier in the summer. The British chose instead to use the Chesapeake as an avenue of invasion and landed at the upper end of the estuary at Head of Elk, Md. on Aug. 25th. After a stormy sea voyage twice as long as expected, the British forces were in poor condition and most of their horses were sick or dead.

Therefore, the English army's movements were slow; they made their way north towards Philadelphia in a series of Delaware skirmishes, avoiding the main American force. Howe marched inland in an attempt to flank the American army and push it back against the Delaware River. Hemmed in by Howe's soldiers on one side and the massed guns of the British fleet on the other, Washington would have had to surrender and end the Revolution. Divining the enemy's intent, Washington dropped back from his established positions near Wilmington and on Sept. 9th set up a strong defense line along the Brandywine, the last natural barrier short of the Schuylkill on the edge of Philadelphia. (You may follow this campaign by referring to the regional map on this brochure's last panel.)

By Sept. 10th the British army was camped around Kennett Square; the American advance under Gen. Maxwell was 3 miles east of Kennett, probing to test the British strength. Finding Washington firmly dug in across the Brandywine (swollen by the frequent recent rain), Gen. Howe made the daring decision to divide his force into two columns. One, ca. 5,000 men, under Hessian Gen. Knyphausen, was to stage mock attacks on Washington's front to keep the Americans expecting an attack at Chadds Ford, while the second column, ca. 7,500 men, under Generals Howe and Cornwallis, was to take a circuitous route 6 miles north and 3 miles east to outflank the American right and come in behind the Continentals. This tactic had been used successfully against the Americans the previous year at Long Island; it was nearly successful at Brandywine.

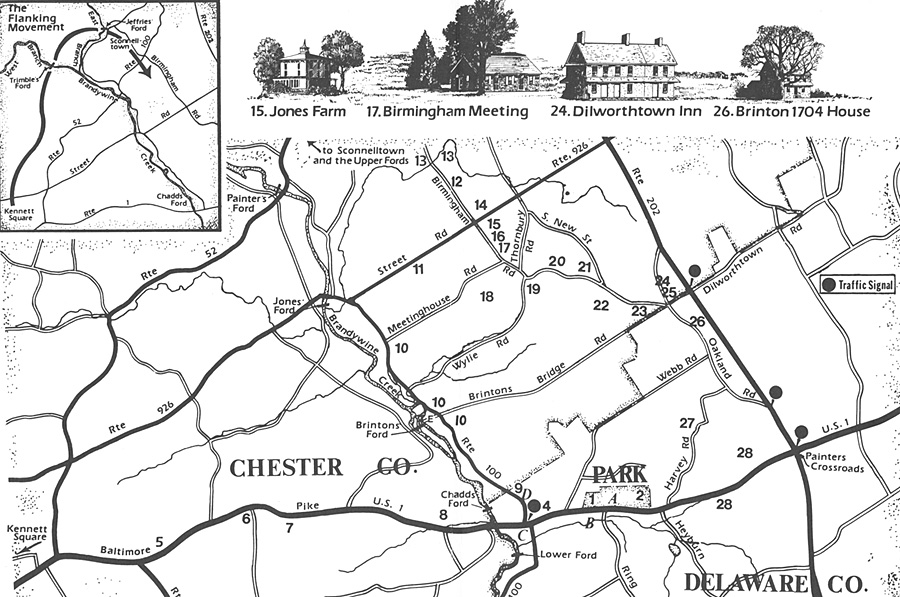

This driving tour will show you the geography, terrain, and actual positions of each army and will follow in detail the actions of Sept. 11, 1777. Despite recent suburban growth, this part of the Brandywine Valley retains its rural heritage and much of the terrain you will cover is little changed from Revolutionary days. The rolling hills and creek valleys of the Brandywine, more heavily wooded than today, made for confusion and piecemeal fighting.

Brandywine was one of the few times that the commanding generals, Washington and Howe, ever faced each other directly. The British had between 12,500 and 18,000 troops. (It is not known exactly how many were still on the sick list after the catastrophic voyage.) The Americans numbered about 11,000.

Driving Tour

This driving tour begins with the 2 properties within the State Park; tickets are available at the Visitors' Center. Turn L then R at foot of hill, arriving at (.3 mi.)

1. WASHINGTON'S HEADQUARTERS.

At this reconstructed farmhouse of Benjamin Ring, you will hear what 18th century rural life was like in PA before the battle. Retrace route past the Visitors' Center. Arrive at (.8 mi.).

2. LAFAYETTE'S QUARTERS.

This is a typical Quaker homestead with interesting outbuildings. Here the guide will explain the aftermath and impact of the battle. Before leaving, note the 1750's sycamore by the house and the pair of sycamores planted by the pond, an 18th century method of marking potable water.

Turn L on the Park road and R on U.S. 1. On your R is the sexton's house (1.0 mi.) and the

A. BRANDYWINE BAPTIST CHURCH. Though in the colonial style, the church and its graveyard post-date the Revolution. The building ahead on the L (1.4 mi.), opposite Washington's Headquarters, is a 19th century mill built on the site of Benjamin Ring's mill. This structure became the

B. ART STUDIO OF HOWARD PYLE, well-known illustrator and founder of the Brandywine School of art at the end of the 19th century.

You are passing through the area where American reserves under Gen. Nathanael Greene waited and are approaching the Brandywine River and the village of Chadds Ford (2.0 mi.). Take the L turn lane and turn on Route 100 S (Creek Road), opposite the old stone tavern. Follow this for 1'/z miles, tracing the positions of Wayne's forces and the PA militia. Where the road skirts the Brandywine's main channel (2.8 mi.), there is a turnout on the R.

The Brandywine, its swift flow swollen by recent heavy rains, seemed a good defense line. Unfortunately its waters had subsided enough by the day of the battle that all the fords were easily passable. This section and Rocky Hill, on your L, was held by PA militia under General Armstrong, veteran of the French and Indian War. As you pass another river outlook (3.1 mi.), note how the valley narrows and becomes steep. Militia was assigned to this area as the terrain seemed to preclude a British attack.

Across the rolling pastures, you will see the stone-arched bridge (3.4 mi.) which marks the site of

3. PYLE'S FORD.

This ford and Corner Ford, a short way downstream, were the southernmost crossings guarded by the Americans. No heavy fighting took place in this area. However, the militia's presence helped to discourage any enemy flanking movement.

Make a U-turn just before the bridge where there is a broad private entrance. The turtles on the gateposts symbolize the Turtle Clan (Okehocking) of the Lenni Lenape (Delaware) Indians, who had a 17th century settlement in this vicinity. Return to

4. CHADDS FORD VILLAGE,

here in 1777, although most of the present structures date from a later period. At the intersection of Rts. 1 and 100 (4.9 mi.), turn L, watching the traffic carefully. Shortly on the L, you will pass

C. THE BRANDYWINE RIVER MUSEUM AND CONSERVANCY. This nationally known art museum occupies a converted 19th century grain mill and is well worth a visit.

Drive straight S on U.S. 1 for 3 miles. Crossing the modern bridge which approximates the old ford's location, the main defense line of the American army is behind you and you are following the route of Maxwell's light infantry, sent forward to scout the British army which had camped 5 miles W at Kennett Square. Most of these picked troops formed a thin line stretched out on either side of the road along the ridge now known as Chadds Peak (6.0 mi.?. They moved slowly forward to the crest of the next hill (7.1 mi.) where the Pennsbury Municipal Building now stands.

A small detachment kept watch further ahead at a local tavern not now standing. While refreshing themselves there, they were almost captured by the advance guard of Knyphausen's column. The Continentals sent back for reinforcements and scurried down the road to take cover behind the stone perimeter wall of

5. OLD KENNETT MEETING (8.1 mi.).

Turn R into entrance for "Kendal at Longwood" and take immediate R. Park by meetinghouse.

In 1777, the road passed on either side of this meeting, so that the wall you see would have faced the oncoming British. Concentrated fire from behind this breastwork forced the English into line of battle. Fighting raged here at 10 a.m., while the Quakers held mid-week Meeting within. One recorded that "while there was much noise and confusion without, all was quiet and peaceful within." Established in 1710, Old Kennett Meeting is still active. Note the mounting block for riders and carriage passengers, and low gravestones in keeping with the Quaker principle of simplicity.

Turn L and retrace your path to Chadds Ford. This 3 mile stretch saw a running battle of ambush and flank movements. Local men familiar with the terrain were with the Loyalist troops, so the English managed to dislodge the Americans from every strongpoint. One such site was the

6. WHITE BARN COMPLEX

of 1730s stone houses and barn at the T-intersection of U.S. 1 and Hickory Hill Road (9.1 mi.). Although the 800 Americans under Maxwell had to retreat, they inflicted heavy losses on Knyphausen's Hessians. A Virginia captain and future Supreme Court Chief Justice, John Marshall, was wounded in this vicinity. Another landmark is

7. THE BARNS-BRINTON HOUSE,

a 1714 tavern on R (9.8 mi.). This site is open to the public seasonally. Turn R just after tavern and park in small lot on far side. In 1777, the road ran on this side and continued, lying R of present-day Route 1.

Continue R. At the Chadds Peak ridge (10.3 mi.), the Americans took a final stand, but the redcoats flanked them by moving through the small ravine and forced Maxwell's men back across the ford. By midday, the Americans returned to the E bank, with the British artillery holding the hills on each side of the road (11 to 11.2 mi.). A stone wall runs parallel to the road on R and the

8. CHADDS FORD ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

is located on N. Both armies maintained a steady artillery bombardment across the Brandywine, whose wooded bottomlands protected troops stationed along the river. Recross bridge and turn L at traffic light (11.6 mi.), taking Route 100 N. Pass the D. CHRIS SANDERSON MUSEUM (11.7 mi.), which fatures battle relics and regional history. Ahead is the

9. JOHN CHAD HOUSE (11.8 mi.).

Park in small gravel lot on L, just past springhouse. On hill behind this c. 1725 home of local ferryman was the main American artillery redoubt under Col. Thomas Procter. Anthony Wayne's soldiers were mustered along the road in front of and N of house. Both house and springhouse are restored and open to the public seasonally.

Continue N along this 18th century road for 3 miles, following the line of the

10. AMERICAN CENTER AND RIGHT DIVISIONS,

under Generals Wayne and Sullivan. (You will pass small farmsteads such as 1830's "Roundelay" (12.3 mi.).) There were 7 major and several smaller fords on this stretch of the Brandywine; all are called by one or more local names. The Americans were confused by the number and the names, and failed to put all the fords under surveillance. General John Sullivan, who held this area N to the forks of Brandywine believed there was no crossing less than 12 miles N of his outposts. He was wrong, and for that reason the bulk of the battle took place where the British column came in behind Sullivan in a repetition of the flanking movement used against this same general the year before at Long Island.

Follow winding Creek Road, noting the cluster of buildings in the valley ahead (12.6 mi.), known as E. BRINTON'S MILL, an 18th century grist mill. Continue past 1839 "Keepsake" farm, Wylie Road (13.3 mi.), and Meetinghouse Road (13.8 mi.).

Throughout the morning, contradictory reports were delivered by couriers riding down this road. These reports, intensified by confusion over location and names of fords, resulted in the American commanders believing that the whole British army faced them at Chadds Ford. No one remembered Long Island.

When reliable information came about 2 p.m., proving that the "dust rising in the backcountry" really was a British column, Washington thought it was a separate force moving N to capture supplies stored at Downingtown and Reading.

At the last minute, Sullivan got word that Howe was about to descend in force upon his rear, and the American right hastened to turn and face this threat. Moving along Creek Road and turning R at Street Road (14.3 mi.), you are following the approximate march of these troops as they hurried to safer positions on the bluffs 400 feet above the Brandywine. Sullivan's brigades moved piecemeal and came into line wherever the commanders found high ground.

11. THE 2 SERPENTINE (green stone) FARMHOUSES

you pass on the R (14.7 and 14.9 mi.) were probably here in 1777. Sullivan brought one brigade into line along here, facing N (your L), only to find that he was ahead of and detached from the rest of his command. Skirmishers from his other brigades under DeBorre, Stirling, and Stephens formed along the wooded ridgeline to your R.

Turn L on Birmingham Road (15.6 mi.); you are leaving the outnumbered Americans behind and are moving towards the British forces under Cornwallis and Howe. Their soldiers, having marched in excessive fog, heat and humidity since before daylight, had made a successful 17 mile hike crosscountry and were in a position to destroy the American army. However, Howe allowed a break so his men could regroup and eat for the first time that day. This delay allowed the Americans to move into position. In the Davis tenant house, the frame and stone building on R (16.0 mi.), and in the main

12. DAVIS-SHARPLESS HOUSE

of serpentine stone on R (16.3 mi.), General the Earl Cornwallis and his officers rested. Continue to crest of

13. OSBORNE'S HILL (16.6 mi.),

where you will turn L into entrance to Radley Run Estates. Park along entrance and climb to top of mound. From Osborne's Hill, stretching from here uphill across the road (site of Howe's observation post), look across the rolling landscape to the farthest ridge, where the American line was forming. The main British column fell into ranks immediately in front of you. Ahead and to L, skirmishers went forward about 3:30 p.m. to start the main battle.

Drive around loop and turn R back onto Birmingham Road to retrace your path. You are now moving as the advancing British line did. The deep folds of land with the small streams and woods made it difficult for either side to see more than their immediate sector. Skirmishers clashed in the broad fields of the 1740 Daniel Davis farm, now renovated as

14. "FAIR MEADOW FARM",

on your L (17.4 mi.). Pause on gravel shoulder just before Route 926 intersection, Street Road (17.7 mi.). Ahead on R, Sullivan's men reformed even as they were attacked. Behind the modern houses of "Revolutionary Farms", where there is a thin line of trees, these soldiers from VA, PA, and MD measured their chances against the oncoming redcoats. This was the cream of the British Army: the Guards brigade, the Grenadiers, the 17th, 44th and 64th of Foot, advancing to attack from behind your R. Sweeping down from Osborne's Hill came the redcoat Regulars with Hessians and dragoons leading across the road in your front, then lined with rail fences, and into an apple orchard which stood where the modern houses are ahead on your L. The cupola you can just see behind them was added to the

15. SAMUEL JONES' FARM

when it was expanded in the 19th century. Now known as "Linden Farm" (17.9 mi.), this building was a rallying point for the American skirmishers as they were slowly driven back from the road and orchard. Continue S on Birmingham Rd. driving slowly so you will see the stone-walled entrance to

16. THE LAFAYETTE CEMETERY

on L (18.1 mi.). Turn L into it, proceed to where road divides, and park. You can now look backward over the terrain the British crossed to attack this improvised patriot line. Osborne's Hill is in the far distance. The 3 monuments along the entrance road, commemorate Lafayette, Pulaski (both of whom had their first American battle experience on this field), and 2 locally prominent men, Colonels Isaac Taylor and Joseph McClellan (both of Wayne's brigade).

The low stone wall behind and S of these monuments marks the edge of the 18th century Quaker burial ground. As at Kennett, this wall protected a small number of Stirling's troops who held off the enemy while the main American line formed on the ridge just S of the meeting house.

Take R-hand turn through the cemetery past the ground-level mortuary Beyond the cemetery turn R and stop. On L is a rare octagon schoolhouse, 1818 `Harmony Hall" which has been restored and furnished in the period.

17. BIRMINGHAM FRIENDS' MEETING

is on R. This is an active Quaker meeting and visitors are welcome. The structure dates from 1763 and was a hospital for American sick before the battle and later for wounded of both sides.

Park and walk beyond the mounting block into the old walled cemetery, where the Americans held off the British against heavy odds. To R is a low granite block marking the resting place of dead from both sides, buried in one commongr ave. Note also the farm complex across the road from the meeting grounds. Part of this "Battlefield Farm" house stood during the battle.

Leaving the meeting turn L and continue S on Birmingham Road. On

18. THE RIDGE

just ahead and to the R, known as "Skirmish Hill" or the "plowed field", the main American line formed and Sullivan's men who were too far forward along Street Road joined their compatriots. Pass the 1847 former Friends' Meeting and schoolhouse (18.3 mi. ). The American brigades under DeBorre, Stirling, and Stephens fought back and forth 5 times across these rolling fields, in hand-to-hand combat with the British until the Continentals retreated and formed a

19. SECOND LINE AT WYLIE ROAD (18.5 mi.).

Marked by a Civil War cannon at the corner, this road approximates the stand taken by Sullivan's remnants and Conway's brigade. The intensity of the fighting in this area is shown by the casualties of the redcoat 64th Foot, which lost all its officers and 2/3 of its men wounded or killed.

By this time Washington realized that the enemy at Chadds Ford was a secondary force and that the main battle was being fought 3 miles away. He therefore led reinforcements from Greene's 2 brigades N. The men ran over the rough terrain, making 4 miles in 45 minutes to help their outnumbered fellows.

Continue S along Birmingham Road as it bends L, noting remains of Wistar's Woods which in 1777 was so thick that when the Grenadiers and Guards attacked through this area, they were lost in the woods for over 2 hours and emerged in another part of the field altogether.

Take L-hand turnout at the bend (18.7 mi.) where a

20. SLENDER GRANITE COLUMN

stands in front of a frame house. This memorial was erected in 1895 by local schoolchildren in honor of Lafayette, who helped to form the third American line near here.

By late afternoon Greene's two brigades formed in the cornfield you see when you turn L and continue along the road. Ahead on the edge of the field (18.8 mi.), a cannon's muzzle points to the center of the field where the road used to run. Lafayette was wounded in the left thigh as he rallied the troops here. Constant use had worn the farm lane down until a miniature pass was formed. Known as

21. "SANDY HOLLOW",

this gap was fiercely defended at bayonet point by Weedon's and Muhlenberg's VA brigades. Heavy casualties were taken by both sides. When the Americans learned that their left wing had withdrawn from Chadds Ford down the Chester Road (U.S. 1) and was safe, these brigades retreated in the twilight. (You pass the cannon at 19.0 mi.).

Continue along Birmingham Road, noting the farm ahead on R,

22. THE BENNETT FARM,

became a dressing station for the Sandy Hollow casualties and is the location where Lafayette was tended. A mile beyond is DILWORTH CROSSROADS (19.9 mi.), where the last action was fought at nightfall. On near R is the

23. 18TH CENTURY BLACKSMITH SHOP,

still in business, which made arms for the French and Indian War as well as for the Revolution. The blacksmith's house beyond it along Brinton's Bridge Road has an early log section and is being restored. On the N side (L) is the brick

24. 1758 DILWORTHTOWN INN,

a popular stop on the Old Wilmington Pike, This 18th century main road, now Oakland Road, has been replaced by U.S. 202 a short distance E. Local patriots were temporarily imprisoned in the inn's cellar by the British, to prevent Washington from learning that the redcoats had ceased pursuit. Today, the Inn is a gracious place to dine.

25. THE COUNTRY STORE,

built in 1758 as store and saddlery, is one of the oldest general stores in continuous operation in the USA. Its old counter was reputedly an operating table after the battle.

Take far R, Oakland Road, S. In this area British soldiers stacked arms and camped the night of the battle. Officers took over focal houses including the medieval-style

26. 1704 BRINTON HOUSE

on your L (20.3 mi.). This architectural gem is open to the public. On leaving the 1704 House, turn L and continue S on Oakland Road. Turn R at intersection of Harvey Rd. (20.8 mi.). This small farm road will take several sharp jogs and bring you past the 1754 Gilpin Mouse (21.3 mi.), which served as

27. GENERAL HOWE'S HEADQUARTERS

for 5 days after the battle. Here the British commander received American doctors brought under flag of truce to treat the Continental wounded. Harvey Road loops past it and its cheese and spring house, now a residence, to continue down the small valley formed by Harvey's Run.

When Washington took the bulk of his army N to the Sandy Hollow area (21.), Gen. Knyphausen pressed his troops across the Brandywine near the River Museum. Despite heavy losses caused by Procter's American artillery firing at pointblank range, the Hessians and Queen's Rangers floundered through chest-deep water and overwhelmed the remaining Continentals of Wayne's division. Abandoning most of their guns and suppplies, these American troops beat a fighting retreat from the ford to your R (W) across this rugged series of ravines.

Stop just before the intersection with U.S. 1 (22.1 mi.). Down this main road from your right came Wayne's fleeing soldiers, closely followed by the Loyalist and Hessian troops. On the high ground to your left, just short of

28. PAINTER'S CROSSROADS,

now the modern intersection of U.S. 1 and 202, Wayne's men made a last stand at dark and held the vital escape route towards Chester and Philadelphia. Disorganized and low on ammunition, Washmgton s troops retreated all night on the 11th. After regrouping on the Delaware River, the Continentals moved N to confront British detachments later at Malvern and Paoli and eventually to defend Philadelphia from behind the Schuylkill.

Turn R and return W along U.S. 1 to the Brandywine Battlefield State Park, passing Lafayette's Quarters and return to the point where you started. The displays, books, and maps available at the Visitors' Center will give you further details on the action.

AFTERMATH OF THE BATTLE

Darkness caused the fighting to diminish into skirmishing. The American army, fragmented and exhausted, was in full retreat to Chester, 12 miles to the southeast, with its light horse under Count Pulaski protecting the withdrawal. The British army, just as tired and disoriented in an unknown, hostile countryside, decided to rest on the field. It stayed 5 days in the area before manoeuvering again.

Darkness caused the fighting to diminish into skirmishing. The American army, fragmented and exhausted, was in full retreat to Chester, 12 miles to the southeast, with its light horse under Count Pulaski protecting the withdrawal. The British army, just as tired and disoriented in an unknown, hostile countryside, decided to rest on the field. It stayed 5 days in the area before manoeuvering again.

The wounded from Brandywine were treated in private homes, taverns, and churches over a wide area. The British wounded were transported to Wilmington and the safety of the British fleet; the Americans were treated by their own doctors and removed eventually to the large hospitals at Ephrata Cloisters and Bethlehem. Washington estimated his losses in killed, wounded, and captured at 1300; Howe gave his losses at 578, but papers captured later in the campaign show a more likely figure to have been 1,976. Roughly 13% of those fighting were lost, a very high rate for the warfare of that time.

The Continental Congress fled inland to the city of York. Money, supplies, and anything that might aid the enemy such as metal to melt down for cannon and bullets, was hidden or removed. (The Liberty Bell was carried to a church crypt in Allentown.) On Sept. 25th the British marched into Philadelphia and settled down for the winter.

The civilian population in the Brandywine area suffered heavy damages. Not only were livestock, wagons, flour, and other food supplies taken with little or no payment by either army, but damages filed later reveal widespread looting of clothes, books, furnishings, and money by the British army. Without farm animals to help gather and transport the harvest, some families faced starvation. In an effort to prevent the British from turning captured grain into edible flour, Washington ordered the removal of all grind stones from mills in Chester and Delaware counties. This caused greater hardship for civilians than for soldiers.

Seed for spring planting had been stolen as well, and plowing was difficult without oxen or horses. Tax rolls indicate that the region took almost 5 years to recover the productivity it had enjoyed before the Battle of the Brandywine. Epidemic sickness followed in the wake of the armies, intensified by the lack of clothing and food during the winter of 1777-78. Fences had to be rebuilt, homes repaired, buildings which had been hospitals required considerable work before they could be used again. Because the area was raided systematically and frequently during the winter by both the British in Philadelphia and the Continentals in Valley Forge (see below), many families who had fled the Brandywine temporarily at the time of the battle were afraid to return until both armies had moved on.

Washington's army was defeated at the Battle of the Brandywine, but not routed; indeed, many units believed they had inflicted heavy casualties on the British and had only been forced to retire by the flanking movement. Reforming on the heights behind the Schuylkill, the American army attacked the redcoats at Germantown on Oct. 4th. After further attempts to dislodge the British and interrupt their supply lines into Philadelphia, the Continentals retired to winter quarters at Valley Forge on Dec. 19th. This fall campaign had lasted well into the severe winter, and the Americans suffered from having abandoned at Brandywine their wagons, food supplies, and personal gear such as shoes, blankets, and overcoats. Food rotted in York and Lancaster for want of transportation to Valley Forge. After the bitter winter the American army emerged, renewed and retrained, to drive the British out of the mid-Atlantic area. After the battle of Monmouth in June, 1778 the main fighting moved to the southern states and never again would this area be seriously threatened.

General William Howe learned at Brandywine that the Americans could be defeated but not conquered; he resigned his command and returned to England in the spring of 1778, leaving the fighting to other British officers who had been his subordinates. Gen. Cornwallis would meet Gen. Washington again at Yorktown in 1781, where a decisive American victory would signal the end of the war.

Battle of Brandywine: Sep 11, 1777

- Introduction and Driving Tour

The Battle

The Battlefield Today

Washington's HQ (Benjamin Ring House)

Lafayette's HQ (Gideon Gilpin House)

The Sanderson Museum

Back to List of Battlefields

Back to Travel Master List

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 2003 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles concerning military history and related topics are available at http://www.magweb.com