Background to the Battle

Background to the Battle

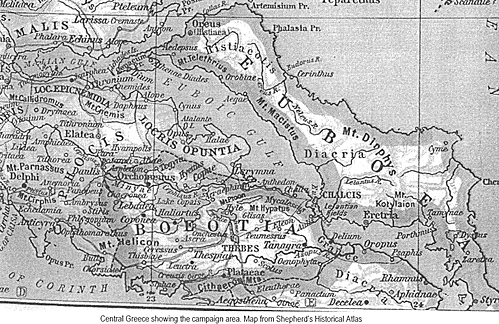

Fresh from the troubles after earthquake of 466 BCE and subsequent helot rebellion, the Ephors of Sparta received a request from the Boeotian City State Thebes in 457 BCE. The Phokians of Central Greece had launched an attack on neighboring Doris to their north, a small state that had a distinct affiliation with Sparta, and Thebes wished that the Spartans send aid against their traditional enemies. They knew the Lakedaemonians believed Doris was the starting point from which the descendants of Herakles instituted their seizure of the Peloponnese, which led to its control by the peoples of Dorian stock, so they were reasonably sure Sparta would respond. However, the request for the Lakedaemon intervention from Thebes was double edged. Not only did Thebes wish her to send troops, but Thebes wanted her to enter a war. Athens was at war with Corinth, Aegina, and Epidaurus, three of the most important allies of the Peloponnesian League. If Lakedaemon did not act now the war party believed her hegemony with the League was at an end.

The Ephors considered Doris their mother city and immediately prepared to send help. However there was the problem of getting troops to Boeotia so they could enter Phokia. They could not go the traditional way through the isthmus. The Athenian capture of the Megarid plain barred a Lakedaemonian army from marching into Boeotia from the direction of the Peloponnese. Fifteen hundred Spartiates with ten thousand allies under the leadership of a Strategos Nikomedes, commanding in place of the young King Pleistoanax, made their indirect way north, by using the Gulf of Corinth. Once in Central Greece the army moved against the Phokians, forced their retreat, and restored Doris. (Thuc. 1.107.1-2)

Now the army was ready to quit central Greece and return home, but old Athenian oligarchs who were against the Athenian democracy, decided they could not live happily under the post-Areopagite constitution and came to Thebes. Their assurance of aid helped decide Nicomedes to stand and resist any Athenian invasion of Boeotia. Because one was certainly coming.

Nicomedes' confidence though was in Thebes. Real estate in Greece was often the source of conflict for desirable territory on the borders between the neighboring states. This was not the case with Athens and Boeotia, of which Thebes was the paramount city, who shared a lengthy boundary. The Parnes mountain range was likely the reason as it made border violations difficult. Boeotia and Attica, were both large and prosperous regions where there was no want for additional lands. The reason for their conflict was political. Thebes was jealous of Athens. Athens had been able to unify her Attica so successfully that every dweller was a citizen of Athens and not of his deme. Thebes had not been able to do the same thing in Boeotia. Even at its strongest point Thebes was the head of a confederation of individualistic towns with strong local loyalties and varying measures of alliance to Thebes.

In 519 the Athenians became entangled in Thebes' attempt to reinforce her control of Boeotia. They intervened on behalf of the Plataean independence against a Theban attack. Their success earned the enduring friendship of Plataea and the hostility of Thebes. Thebes first chance to pay Athens back was in 506 when King Kleomenes took a Peloponnesian League army into Attica to put down the Kleisthenic democracy. They joined with Kleomenes and the allied army to attack Athens from three sides, by seizing the Attic border districts of Oinoe and Hysiae.

However the Corinthians refused to cooperate and the Peloponnesian force returned home. Exempt now from attacks from the South, this allowed the Athenians to march against the Thebans and her allies the Chalcidians, defeat them, and reduce their power. This turn of events angered the Thebans even more and they intrigued with the Island ofAegina and helped bring on the first of a series of conflicts between Aegina and Athens. Athens revenge was quick. The Thebans suffered another defeat and their plan for retribution was a failure. Worse, Plataea remained independent and even more attached to Athens.

The Persian War added additional issues to the rival city states. Athens fought for freedom while Thebes was a Persian puppet. To add insult to injury, Athens routed the Theban army (again) at the invasion's defeat at Plataea. This result was a serious diminution of Theban authority and leadership paralleling the rise of the Athenians'. The Theben Boeotian confederation was dissolved and each city given its independence. An oligarchy seems to have replaced the "dynasty" who ruled Thebes.

It was under this backdrop that the Thebans invited the Lakedaemon army to come into Boeotia and "to help their city to gain the entire hegemony ofBoeotia." (Diod. XI.81.2.) Diodoros gives the evidence ofthe reason for Sparta's taking a large army out of the Peloponnese to reestablish Theban supremacy in Boeotia at the same time that it was unable to invade Attica. Diodoros says that the Thebans promised that in return for Sparta's help, "They would themselves make war on the Athenians so that there would be no need for the Lakedaemonians to bring an army outside of the Peloponnese." (Diod. X1.81.1.) The Ephors were attracted to such a prospect and agreed to the proposal, "judging that it was advantageous to them and thinking that if the Thebans became more powerful they would be a sort of balanced antagonist to the Athenians."(Diod. IX.81.2-4)

When Athens heard that the Lakedaemonians were still in Central Greece and were helping fortify the city ofThebes while forcing the Boeotian cities to become subject to Thebes, they had no choice but to intervene. They marched into Boeotia with the entire force available to them, accompanied by allied contingents including one thousand selected Argives. The Athenian army was fourteen thousand men in addition to a detachment ofThessalian cavalry ofperhaps 400 hundred strong (Thucydides I. 107.5-7.) The two armies would met at Tanagra. Battle of Tanagra 457 BCE Order of Battle

Delian League

CIC Myronides (Good/Inspiring)

Athenian Hoplites 9,000 HI. Body armor; Long trusting spear; large shield. Average training

Delian League Hoplites 3000 HI. Body armor; Long trusting spear; large shield. Average training

Argive select Hoplites 1000 HI. Body armor; Long trusting spear; large shield. Good training

Athenian Noble Horse 500 HC Body armor; Javelins Average training (May dismount as Hoplites)

Thessalians light horse# 400 LC Cloth, Javelins or long spear Good training.

Athenian Psioli 2000 SI Cloth, Javelins Poor training

Delian Psioli 200 SI Cloth, slings Poor training

Peloponnesian League

Nikomedes CIC (Excellent/Objective)

Spartiate Hoplites* 1500 HI. Body armor; Long trusting spear; large shield. Superior training

Helots 500 SI Cloth, Javelins Poor training

Perioikoi 3000 HI. Body armor; Long trusting spear; large shield. Good training

League Hoplites 5000 HI. Body armor; Long trusting spear; large shield. Average training

Theban Hoplites 1000 HI. Body armor; Long trusting spear; large shield. Average training

Theban Aristocrats 600 HC Body armor; Javelins; Good training.

Athenian Oligarchs 100 HI. Body armor; Long trusting spear; large shield. Average training

Boeotian Peltasts 1000 LI Cloth; Javelins; medium shield; Average training.

League Psioli 1500 SI Cloth; Javelins; Poor training

# The Deli an/Athenians lost because their Thessalian cavalry defected at the start of the battle. Before deployment roll one d10

- 0-1 No defection. Force stays loyal.

2-4 50% of the force defects. Add to the Peloponnesians.

5-9 100% of the force defects. Add to the Peloponnesians.

* Spartiates We assume that these are true peers of the city of Sparta and undiluted by the addition of Perioikoi. Hence their high rating.

The Field and Deployment

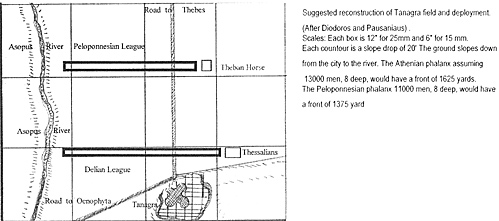

Tanagra sits low mound at the junction of the River Asopus and a large stream overlooking a plain drained towards the Asopus (See Map). Diodoros [XI 80 2.] claims that the Athenians reached Tanagra first. There is no reason to doubt this, and they formed line of battle with the city to the army's back and its left flank resting on the Asopus. Presumably the Argives took the left, while the Athenians took the right position of honor, leaving the Delians the middle. The Thessalians would be the far right so they could maneuver (and easily defect). The Athenian cavalry is not mentioned, perhaps it dismounted, acting as hoplites. We know that it was there, we have several grave steles ofAthenian cavalrymen who died at Tanagra.

Suggested reconstruction of Tanagra field and deployment. (After Diodoros and Pausaniaus). Scales: Each box is 12" for 25mm and 6" for 15 mm.

Suggested reconstruction of Tanagra field and deployment. (After Diodoros and Pausaniaus). Scales: Each box is 12" for 25mm and 6" for 15 mm.

Each countour is a slope drop of 20' The ground slopes down from the city to the river. The Athenian phalanx assuming 13000 men, 8 deep, would have a front of 1625 yards. The Peloponnesian phalanx 11000 men, 8 deep, would have a front of 1375 yards.

The Spartiates would occupy the position of honor on the right. This meant they were facing the Argives, and would explain the high casualty rate among the Argives. The Perioikoi would be on the Spartans left, followed by the league hoplites, followed by the Thebans and their horse on the left.

The Battle The Athenian force was larger, but the Thessalian horse deserted to the Lakedaemonians at the start of the battle which tipped the balance. Nikomedes won a victory in which both sides suffered heavy casualties. Although the Lakedaemonians controlled the battlefield at the end of the day's fighting, erected the trophy and returned the Athenian dead under truce, the victory was hollow, for they were unable to continue to stay in Boeotia to assure the overthrow of the Athenian democracy. Nikomedes forced his way through the denuded Megarid and returned to the Peloponnese. Nothing had been solved, the Athenians would soon renew the war in Boeotia and this time there would be no Peloponnesian support.

Back to Strategikon Vol. 2 No. 2 Table of Contents

Back to Strategikon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by NMPI

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com