Rommel in the Desert (RitD) is Columbia Games' block game of the North African theater during World War II. This game has only recently gone out of print and is no longer in Columbia

Games' catalog.

Rommel in the Desert (RitD) is Columbia Games' block game of the North African theater during World War II. This game has only recently gone out of print and is no longer in Columbia

Games' catalog.

Of all of the 60 odd North African theater games I have owned over the years, RitD is one of my two favourites (the other is GDW's Operation Crusader monster game of 1978). No other games come as close to capturing what I understand to be the essence of desert warfare: the inhospitable and almost endless tracts of sand, gravel and rock that impose no limitations on time and space but enormous limitations on supply.

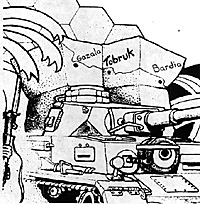

RitD's map is indeed a thing of beauty. It is printed on one piece of heavy cardstock, which is more rigid than the usual paper mgs but less expensive, bulky and prone to warping than the mounted ones. The hexes are huge, which can be disconcerting if you're not familiar with Columbia's Front series, but befit both the blocks and the movement mechanics. The map covers the traditional area of North Africa as first defined in Avalon Hill's Aftika Korps: Libya east of El Agheila and Egypt west of Alexandria. The scenarios, limited as they are by the range of the map, include a well-known selection, ranging from the Italians' initial reluctant advance into Egypt in 1940 to Rommel's final retreat after El Alamein in 1943.

An expansion covering the terrain west of El Agheila and into Tunisia, and including the green American forces, would have been fascinating.

The units are Columbia's standard hardwood blocks: red for the Allies and black for the Axis, with labels identifying each unit and its capabilities. Craig Besinque's original version of RitD (described elsewhere) used yellow blocks to represent supply, instead of the cards used in this last edition. One wonders whether, back then in the Kootenays of British Columbia where RitD was conceived and first produced, wooden blocks may have been cheaper than paper and cardstock because they were least removed from the tree and required fewer manufacturing steps.

There are a vast array of units, including motorized and non-motorized infantry, mechanized, reconnaissance, armor, antitank, artillery and anti-aircraft. These are generally at the brigade or division level. Most units lose one combat factor per hit but the German Panzer units are more fragile (or less likely to be replaced) and lose two, whereas the Allied Matilda armor units are small but beefy and require two consecutive hits in the same battle to lose one combat factor.

Other than the supply cards, the dice and the box, the only remaining component is the rulebook, which is small but not dense. It is fundamentally complete, but not necessarily organized in the most useful fashion for learning the game or for reference. Fortunately the rules are succinct, so it's easy to search through them initially until familiarity improves.

The RitD system is simplicity itself. There are a fixed number of monthly turns per scenario. Each turn starts and ends with some common administrative activities. In between, there can be as many impulses as the players are willing to commit supply to. When both players pass (i.e., refuse to commit any further supply), the impulses are over and the turn enters its final phase.

There are only two types of movement in the basic rules (the errata suggest a third possibility):

- 1) a Group Move, where all of the units in any one hex (there are no stacking

limitations in this game, so a favourite opening setup for the player who moves

first is to put all his units in one hex) may each be moved to a different hex

anywhere else on the board within its movement allowance; and

2.) the Regroup Move, where any and all units anywhere on the board which could all move to one and the same particular hex in one turn, do so.

The basic sequence of one Group or Regroup move followed by battle (MB) requires the expenditure of one supply card. Two supply cards can be spent for either two consecutive moves and one battle (MMB) or one move and two consecutive battles (MBB). Three supply cards can be spent for two complete basic sequences (MB + MB). However, these sequences are governed by the fact that each unit may move and/or attack only once per impulse.

There are no zones of control in RUD. However, a unit or group of units must stop upon entering a hex containing enemy units. Such hexes become battle hexes, and up to three rounds of combat are undertaken in each battle hex per impulse. Battle consists of both players simultaneously rolling 1d6 for each eligible combat unit in the battle hex. In normal combat, as occurs between two infantry units or two armored units, each "6" results in a hit. But some combat, such as armor attacking infantry, has double effect where each "5" and "6" count as hits; and some, such as armor or infantry attacking unsupported artillery, has triple effect where each "4", "5" and "6" count as hits.

The key here is that armor cannot attack any other unit type in the battle hex until all enemy armor has been eliminated from the battle hex, so combined arms operations are preferrable.

If, after three rounds of combat, units from both sides remain in the battle hex, they must stay there and continue the battle in the following tum. Retreat is an option for either side, but not a particularly pleasant or easily-accomplished one. In fact, one should never become involved in combat with the thought of retreating to safety if things should get rough.

It may be possible to save one or two engaged units, but the price is usually the destruction of the remainder of the force. An inexperienced player is likely to continue to commit more units to an unviable battle hex each turn, until he runs out of either units or supply. Even seasoned players have been known to misjudge this way.

The importance of supply cannot be understated. Everything except water had to be brought into the desert theater from elsewhere, generally by sea. The Allies faced two major difficulties: very long and dangerous supply routes from England; and higher supply requirements due both to higher general levels of supply than the Axis on a per capita basis, and also to the fact that there were more Allied personnel.

The Germans faced two major difficulties as well: lower general levels of supply and reinforcement as the North African theater was never as prestigious in the eyes of Berlin, particularly with the planning for Barbarossa; and Malta, which was virtually astride the Axis supply line from Italy. There was just never enough supply to do everything, and therefore resources had to be stockpiled in advance for the next big operation.

The consequences of running out of supply were nothing short of disastrous irreplaceable vehicles abandoned for lack of fuel; desperately-needed weapons unable to fire due to lack of ammunition; overworked and battle-damaged equipment unable to be repaired for lack of spare parts; insufficient food and water to, sustain soldiers in the offensive. So too in RitD. Any friendly unit which is out of supply at the start of the owning player's turn must regain a valid supply line before the end of that turn, or suffer automatic disruption.

Disruption is a temporary but drastic phenomenon. Disrupted units cannot move or retreat, engage in combat, impede enemy movement, cut enemy supply lines or form part of a friendly supply network; in short, they can do nothing except rout. it gets worse. Routed units lose one step and must immediately retreat, suffering further disruption and possible pursuit fire. Routed units which cannot retreat, or which suffer further rout, are eliminated.

In a similar vein, being out of supply cards at a critical point in the proceedings can also be frustrating, or even embarrassing. It requires no supply cards to defend oneself in battle or to undertake a withdrawal. However, if you are out of supply cards but your opponent isn't, you wifl not be able to send more units into a battle hex or exploit a hole in the line. All you will be able to do is attempt to withdraw as many units as possible to safety.

Fog of War

An intrinsic characteristic of Columbia's block system, and one which is particularly advantageous in a desert campaign, is the ability to mimic the fog of war. Although you can see where your opponent's blocks are located, you probably have very little idea of what type they are, how strong they are or how many are dummies. Combined with the ability to generate replacements each turn with Build Points and to replenish any devastated units, and I doubt that even a photographic memory would be much use in recalling your opponent's units.

In this game, supply is everything. Never attempt an offensive unless you have a goodly number of supply cards in hand (although you draw supply cards every month, one-third of the supply card deck consists of blanks). When you do go on the offensive, threaten to outflank with your reconnaissance units (which have the longest range per turn), keep a mobile group in reserve (to exploit breakthroughs and/or cover your own supply lines) and use your remaining available forces at the schwerpunkt of your choice.

One or more reconnaissance units hovering around the southernmost oases will be kept in supply by the oases, and will always be a dangerous out-flanking threat.

On the defensive, be flexible and mobile, and always be aware of the state of your supply lines. Keep a small reserve available as an outflanking threat, to protect your supply lines if required, and to cover the inevitable withdrawals. About the only safely defensible feature on the board is Tobruk. Keep at least one reconnaissance unit there, so if your opponent bypasses Tobruk and doesn't leave a large enough screening force, you can dart out and cut his supply lines to good effect.

Tobruk is well worth fighting to control; it ensures a positional victory if neither a strategic victory (capturing the enemy base or exiting three supplied units from the enemy map edge) nor a decisive victory (having at least twice as many units remaining as your opponent) is won.

If you don't have the initiative on a given turn, it is always worthwhile using a blank supply card to challenge for it. Your opponent may give up the initiative without inspecting your card. This trick should not normally work more than once, however. A more subtle trick is to pass on one or more turns (while you still have several supply cards in hand) when it's obvious your opponent intends to continue; then, when he has started to exhaust his supply cards but before he passes, initiate your own offensive. And Build Points should be used for redeployments, and for building up good units which have taken a beating.

Rommel in the Desert

- Rommel in the Desert: Game Review

Rommel in the Desert: Devil's Advocate (Rebuttal)

Rommel in the Desert: Component Manifest

Rommel in the Desert: Collector's Value

Back to Simulacrum Vol. 1 No. 1 Table of Contents

Back to Simulacrum List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by Steambubble Graphics

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com